I got lost the first time I tried to find UCSB. It was 1967, I’d just been accepted as a grad student in the English Department, I’d never been to Santa Barbara before, and, of course, I didn’t use a map. I carefully drove through Santa Barbara two times on that fateful day—no sign of, or for, a university within the city limits, at least from the 101 freeway. In frustration, I tried a third time but went further north for the heck of it, and, to my bewilderment, chanced upon UC Santa Barbara in a small town called Goleta, 7 miles north of Santa Barbara.

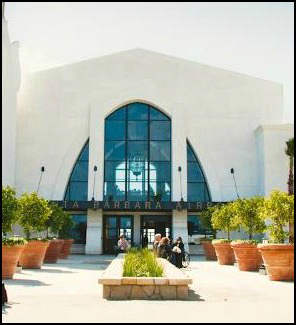

It turns out that UCSB really isn’t in Goleta, at least in a political sense, and neither is the Santa Barbara Airport, thanks to a one-time Santa Barbara Mayor and Superior Court judge by the name of John T. Rickard. Rickard’s name is in the news these days because the Santa Barbara City Council has voted to name the new $63 million airport terminal after him. Why? Because Rickard worked out a crafty geographical plan that “connected” Santa Barbara to land in the Goleta Valley via an underwater “preservation zone” that was mainly designed to bolster tourism and prevent inshore oil drilling.

“The Santa Barbara airport is adjacent to the University of California, Santa Barbara and the city of Goleta. However, the land that the airport sits on was annexed to the city of Santa Barbara by a 7 miles (11 km) long, 300 feet (90 m) wide corridor, most of which lies under the Pacific Ocean. This a shoestring annexation” (source). The land referred to consisted of orchards and the Goleta Slough until 1942 when the Marine Corps Air Station Santa Barbara was commissioned to serve as a “training base for numerous squadrons before they deployed to support combat operations in the Pacific Theater. Later in the war, the station would serve as home to Marine squadrons that were trained to operate from aircraft carriers providing close air support for their fellow Marines on the ground. Following the war, the Marine Corps debated making MCAS Santa Barbara a permanent installation; however the City resisted this proposal since the facility was needed for a municipal airport and no other land in the area was suitable. The air station went on caretaker status March 1, 1946 and was released to the War Assets Administration for disposal two months later” (source).

But back to that “shoestring annexation.” “In some states, municipalities are prohibited from annexing land not directly connected to their existing territory. A shoestring or flagpole annexation allows the municipality to do so. Such annexations are sometimes used when a municipality seeks to acquire unincorporated developed land, such as a newly built subdivision separated from it by undeveloped open space. They may also be used when a municipality desires to annex a commercial or industrial area without taking over intervening residential areas, so as to collect tax revenues from the businesses or industry without having to provide services (such as electricity and garbage collection) to residents. Such uses of the technique are often criticized and derided as a form of gerrymandering, and have in fact been used for the purpose of manipulating vote distribution among election precincts and districts” (source).

Rickard’s shoestring annexation wasn’t about taxes or votes; rather, it was a successful effort to get around the fact that the aforementioned land was not contiguous to Santa Barbara, a factor essential to the annexation process, and it was all made possible by Rickard’s earlier creation of a no drilling sanctuary off our coast in order to “protect beautiful beach recreational and residential areas from desecration by oil well development…” (Santa Barbara News Press, August 27, 1954). In essence, it provided a “means by which the City of Santa Barbara was able to annex the airport property, thereby enabling the city to make improvements, upgrades, operational expansions, and perhaps most importantly, meet necessary federal requirements to retain commercial carriers vital to Santa Barbara’s economic vitality” (Pedro Nava, Letter to the Editor, Santa Barbara View, Nov. 4, 2012).

Nick Welsh, writing for the Independent, put it this way in an August 4, 2011 article titled “Viva El Perro: Why Jack Rickard is the Most Effective Mayor You Never Heard of and Why the New Airport Terminal Should Be Named After Him”:

When California oil companies pushed legislation to open up offshore drilling in state waters up and down the coast, Rickard successfully lead the charge to impose a drilling ban from Summerland to UCSB. He did this, by the way, 15 years before Santa Barbara’s now-historic 1969 oil spill, which originated in federal, not state waters. That drilling ban happened to give the City of Santa Barbara jurisdiction from its shoreline to the three-mile limit, where federal control began. In one of the most brilliantly sneaky legislative moves ever, Rickard would seize upon this obscure fact when seeking to annex 800 acres of land right in the heart of Goleta and home to what was then Santa Barbara’s fledgling airport. A modern airport was seen as key to kick-starting efforts to attract smokeless industries – R&D firms – to the South Coast. County officials were at best indifferent to this effort, at worst hostile. But the city was precluded by state law from annexing noncontiguous land. Rickard devised a way to finesse the “contiguity” issue by drawing a jurisdictional line up the coast from Santa Barbara to Goleta, and then cutting eastward to the airport. As an act of gerrymandering, it doesn’t get more creative or blatant. But it got the job done, and enabled Santa Barbara to annex all 800 acres of airport property. The state legislature, dazzled by Rickard’s ingenuity, passed a law prohibiting anyone else from ever doing the same thing (source).

Those two accomplishments alone would justify naming rights. But there’s a lot more. Under Rickard, Santa Barbarans approved the bond necessary to secure Shoreline Park and to build the Muni Golf Course, the creation of which entailed all kinds of intricate wheeling and dealing. Under Rickard’s tenure, City Hall secured the real estate that would become Chase Palm Park, Parma Park, Ortega Park, and Orpet Park. Not bad. Rickard used the city’s sewer pipes to vastly expand its sphere of influence and control. As the South Coast population swelled, people needed service. Rickard was happy to oblige, but in exchange, he wanted voluntary annexations. That’s how Santa Barbara came to “own” Coast Village Road in Montecito. It’s also how city limits expanded from Alamar Avenue — where it was in ’53 —to Five Points, where it was at the end of Rickard’s regime. Rickard worked hand-in-iron-glove with civic matriarch Pearl Chase and passed the city’s sign ordinance. He passed the laws prohibiting residents from burning trash in their backyards and requiring them to have it hauled away. And in the same breath, he put the city’s trash contract out to bid, successfully giving the business to a less corrupt hauler than the one who then had it. And as an afterthought, he got boat slips built at the harbor for the first time, not to mention a new police station built, and a new downtown fire station, as well. Did I mention that Rickard was a registered Republican whom Ronald Reagan would later appoint as a Superior Court judge? Yes, but somehow that didn’t stop him from pushing for higher taxes when he thought they were necessary. During our current apex of human perversity, Jack Rickard serves as a helpful reminder that there can be more to politics than gratuitous self-destruction. The real question isn’t whether we should name the new airport terminal after him. It’s how could we not? (Ibid.).

Editor’s note: see SBA’s web site for an historic and pictorial timeline of the Santa Barbara Airport’s evolution.

Article by Bill Norrington