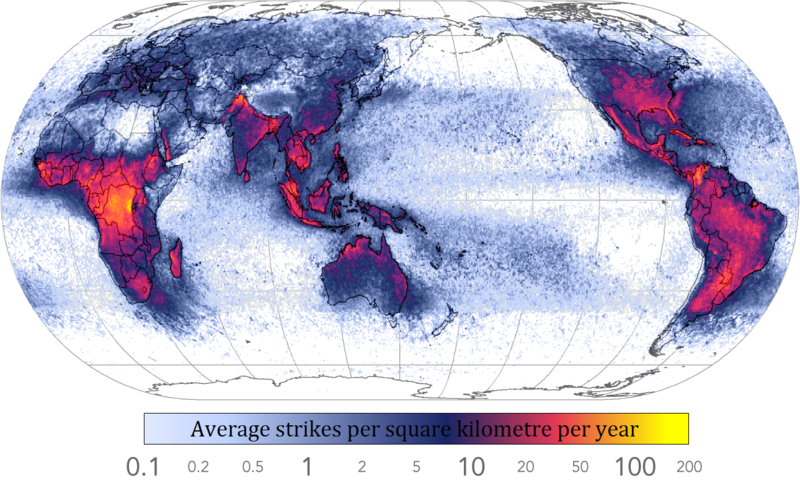

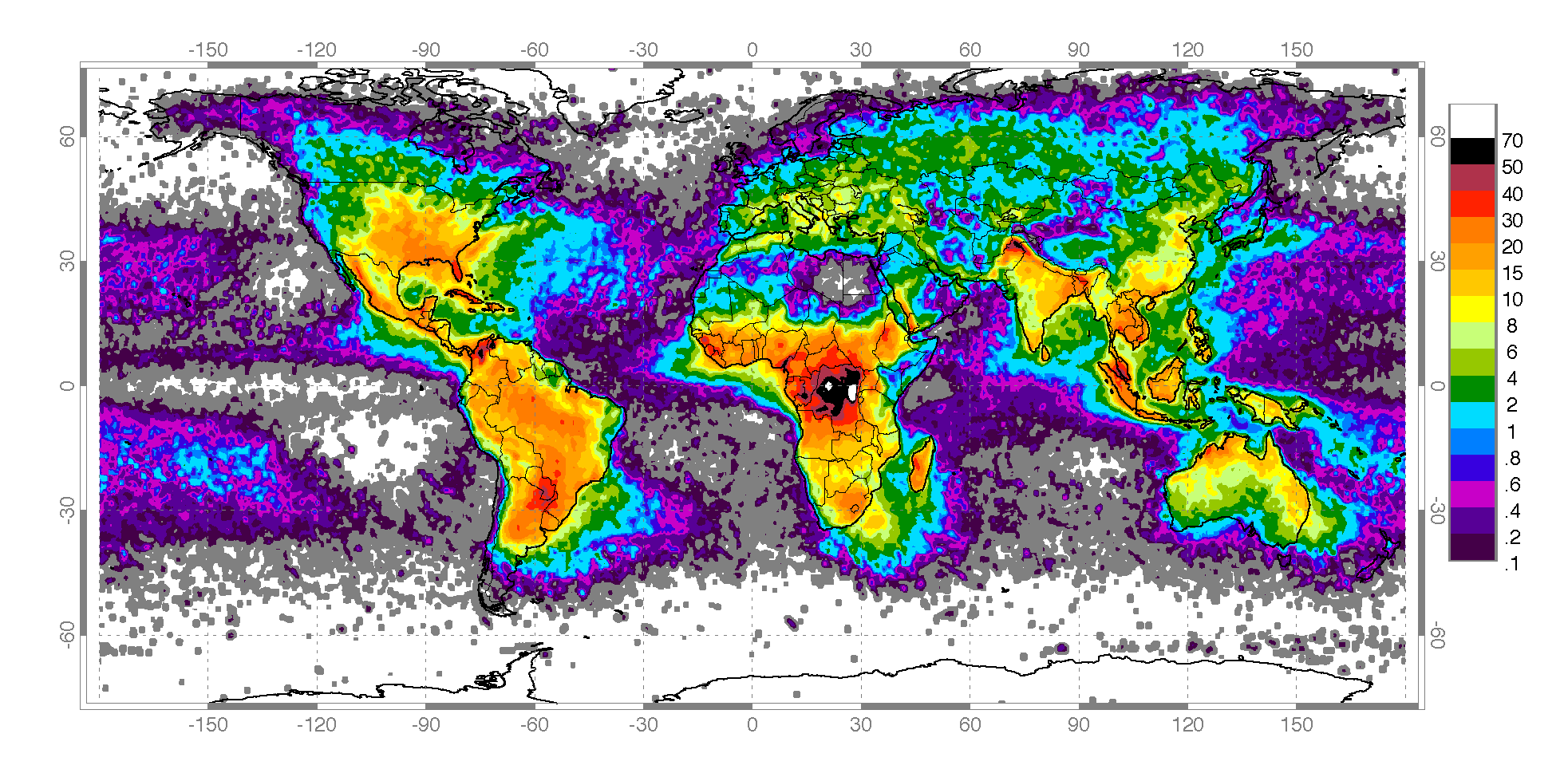

Lightning occurs on average 44 ± 5 times a second, for a total of nearly 1.4 billion flashes per year on Earth, and approximately 70% of lightning occurs in the tropics where the majority of thunderstorms occur. Research is currently being conducted into lightning patterns in the Amazon to determine how clouds are affected by the particulate matter emitted by slash-and-burn fires, and it is hoped that such research will improve our understanding of the impact of pollution on global weather patterns. The following review from NASA’s Earth Observatory web site summarizes one such study:

Native Americans used smoke signals to indicate danger, and a white plume is sent up by the Vatican when a new Pope is chosen. Now, a new research project by Tel Aviv University researchers and their colleagues shows that where there’s “smoke” there may be significant consequences for local weather patterns, rainfall and thunderstorms.

In a new study, Prof. Colin Price, head of Tel Aviv University’s Department of Geophysics and Planetary Science, researched data on lightning patterns in the Amazon to show how clouds are affected by particulate matter emitted by the fires used for slash-and-burn foresting practices. His findings, recently published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters, [Orit Altaratz, Ilan Koren, Yoav Yair, and Colin Price, Lightning response to smoke from Amazon fires, Geophysical Research Letters, Vol. 37, L07801, doi:10.1029/2010GL042679, 2010] could be used by climate change researchers trying to understand the impact of pollution on global weather patterns. Along with colleagues at the Weizmann Institute and the Open University in Israel, Prof. Price demonstrated how pollution’s effects on cloud development could negatively impact our environment. While low levels of particulate matter actually help the development of thunderstorms, the reverse is true once a certain concentration is reached — the particles then inhibit the formation of clouds and thunderstorms. “The clouds just dry up,” he says.

Lightning strikes to the center of the issue: Scientists have known for some time that man-made aerosols affect cloud formation, but specific scientific findings have been inconclusive. How clouds and storms change in response to air pollution is central to the debate about climate change and global warming, since clouds have a general cooling effect on the Earth’s climate. But how man-made pollution impacts clouds, rainfall and weather patterns remains poorly understood, and natural particulates, such as those generated by Iceland’s recent volcano eruptions may add to this effect. The thick volcanic ash cloud absorbs solar radiation, heating the upper atmosphere, similar to the forest fire smoke, and can hence also impact the development of clouds and rainfall, Price said.

While studying the climatology of the Amazon forest during its annual dry season, the researchers noticed how thousands of man-made forest fires injected smoke into the atmosphere. Since thunderstorms still occur during the dry season, it was the perfect opportunity for studying the effects of these particulates on thundercloud development. Cloud droplets form on small particles called “cloud condensation nuclei” (CCN). As the number of CCN increase due to the fire activity, the lightning activity increased in the storms ingesting the smoke. More CCN implies more small droplets that can be carried aloft into the upper parts of the cloud where lightning is generated. Increased lightning activity generally also implies increasing rainfall over the Amazon. But when particulate matter became too dense, they observed, clouds didn’t form, and the lightning activity in thunderstorms diminished dramatically.

Seeking answers to vital questions: These results may have significant implications for polluted regions of the world that rely on rainfall for agriculture and human consumption. “One of the most debated topics related to future climate change is what will happen to clouds, and rainfall, if the earth warms up,” says Prof. Price, “and how will clouds react to more air pollution in the atmosphere?” Clouds deflect the sun’s rays, cooling the Earth’s climate. If we change the duration of cloud cover, the aerial coverage of clouds, or the brightness of clouds, we can significantly impact the climate, Prof. Price and his colleagues explain. And too many aerosols may have disastrous impacts on rainfall patterns as well. Air pollution from car exhausts and smokestacks at power plants and factories contribute to increasing particulate matter in our atmosphere. This is the first study of its kind that uses lightning as a quantitative way to measure the impact of air pollution on cloud development over a large area, and across a number of years. “Lightning is a sensitive index to the inner workings of polluted clouds over the Amazon Basin,” concludes Prof. Price.