The following is an article by Nathan Masters, posted July 28, 2014 on kcet.org’s Social Focus page, L.A. as Subject, with the title above:

Today, Pacific Coast Highway passes effortlessly through Point Mugu between Oxnard and Malibu. But when highway engineers began plotting the route in 1919, the rocky promontory presented a colossal challenge.

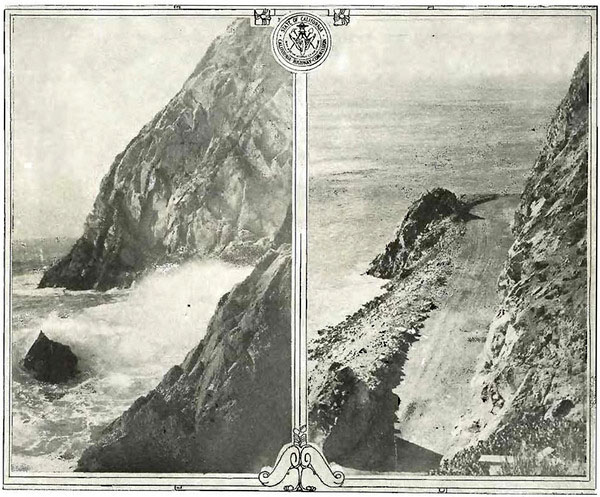

Then, Point Mugu was a near-vertical ridge of resistant volcanic rock — an igneous dike that in a distant epoch intruded the Topanga formation’s softer sedimentary strata–standing some 150 feet tall against the pounding surf. As the westernmost tip of the Santa Monicas, it represented the last hurrah of the rugged mountain range. Just north and west of the point, the land opened up as the Oxnard Plain. (The Santa Monicas don’t truly end at Point Mugu. Instead, geologists speculate, the thrust fault that gave rise to the mountains plunges beneath the waters of the Pacific only to reemerge far to the west as the northern Channel Islands.)

Point Mugu was a formidable barrier to the planned coastal highway, but California’s state highway engineers attacked it with a full arsenal of geologic weapons. First, in 1923-24, they blasted a road cut around the base of the headlands. Workers scaled the cliff with ropes and drilled a series of 30-foot holes into the rock. Into the holes went 18 tons of hand grenade powder left over from World War I and 25 tons of black blasting powder, and down came 108,000 cubic yards of rock — much of it used as fill for the adjacent road embankments. By October 1924, a narrow road snaked around the point where waves once lashed at its stony face.

But a spate of fatal accidents soon proved the alignment to be inadequate. Weather was often a factor, but so was the tight, 275-foot radius curve around the point. Drivers plunged their cars off the road and into the Pacific — sometimes leaving little trace except for bloodstained rocks. The tip of Point Mugu earned the dark moniker Dead Man’s Rock, and in 1930 Inspector Kenneth C. Murphy of the California Highway Patrol appealed to the state highway commission for help. Blow up the rock, he pleaded.

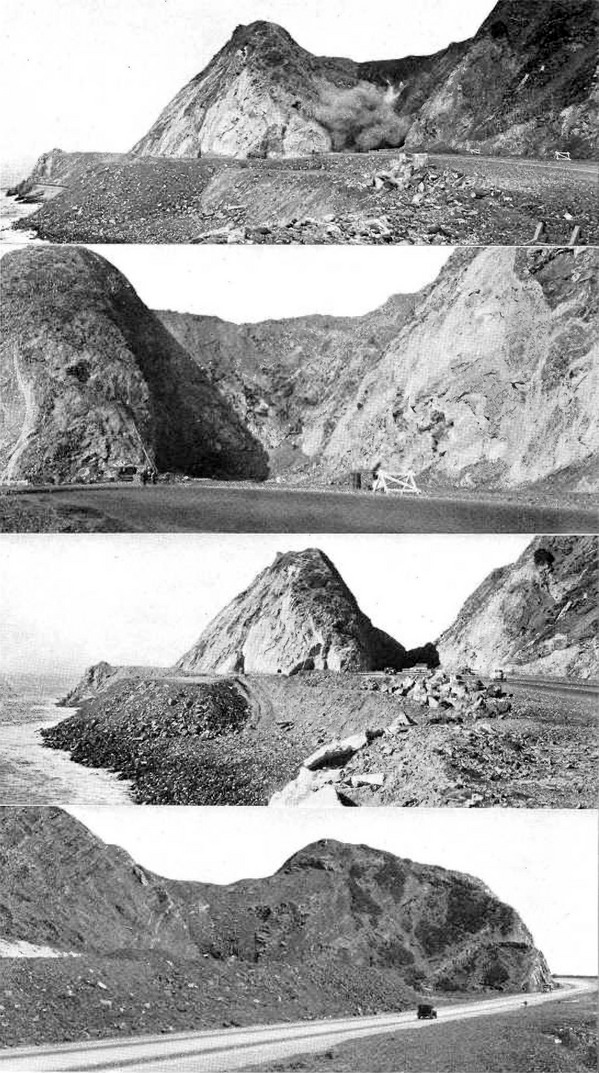

The commission complied. In October 1937, an army of day laborers began carving a 200-foot-deep road cut through Point Mugu. Workers used 107 tons of explosives, a diesel shovel, a bulldozer, ten dump trucks, and five jackhammers to carve out the new 60-foot-wide roadway. Where the highway once bent around Point Mugu, it would now plow straight through the stony wall.

By February 1940, their work was complete. The original road around the rocks survived as a scenic bypass (it’s since eroded away), but the main highway now sliced through Point Mugu, leaving only a rocky stub where the Santa Monica Mountains once thrust themselves into the Pacific with a final flourish.

Editor’s note: Many thanks to Bernadette Weinberg, our Academic Personnel Analyst, for suggesting this material.