Professors Dan Montello and Keith Clarke share tidbits about toponymy below. The first section, “The Entertaining World of Toponymy,” is an overview of the subject by Dan, and the last section consists of extracts concerning the subject which Keith took from Dr. Map, an anonymous authority on all things cartographic.

Toponymy is the study of geographic place names, including natural places like mountains and rivers, and human places, like cities and countries. The word comes from the Greek topos for place and onoma for name. Carving up the world into distinct features and regions, and putting a verbal label on them, is likely a universal human activity, although the particular place where the boundaries are carved is rather variable.

A common question about toponym concerns their origin. We can identify at least five common sources for toponyms. First, we can look to the migration history of a place and the people who reside there. Immigrants bring their culture with them, and place names reflect these patterns of relocation diffusion. Names like New England and Berlin (Wisconsin among others) recall the homeland. But colonists from Britain and other places probably even more often simply appropriated place names from the indigenous people they met in their new homeland. Many U.S. toponyms are American Indian words, including Ohio, Oklahoma, Michigan, and the names of over 20 other U.S. states. A second source of place names can be found in the values and aspirations of residents. Some values are religious (San Francisco, California and Jerusalem, Maryland), some are classical (numerous towns named Troy, Athens, or Rome in the U.S.), and some reflect respect for honored historical figures (both Washington and Martin Luther King lend their names to many entities in many U.S. states and other countries). Third, names often celebrate specific positive or negative events that have occurred somewhere. Eureka in California and Lucky Boy Pass in Nevada celebrate success at gold and silver prospecting, respectively. Death Valley in California comes from the desperate experience of a group of “49ers” headed to the California gold fields in 1849-1850. Fourth, names are often designed to capture accurately the physical character of a place. The Grand Canyon is certainly grand, Thousand Oaks in California had well over a thousand oak trees (and still does), Portage (many states have such a town) describes a place where canoes were carried between water bodies, Minneapolis has several large lakes and rivers (Dakota for water combined with Greek for city), and Glitter Gulch in Las Vegas definitely sparkles with electric lights. Finally, a fifth source of place names is again an attempt to capture the physical character of a place, but in this case, inaccurately or deceptively. Perhaps sarcastically or cynically, several names have been attached to places as a form of black humor or perhaps intentionally to mislead. Everyone is familiar with industrial parks and housing developments given names like Green Meadows or Flor Vista Park, although no meadows or flowers are evident. One of the most famous examples in geography comes from the Norseman Erik the Red, who reputedly named Iceland and Greenland in the 10th century to repel future visitors from the first place, a relatively balmy emerald jewel, and attract them to the second, a relatively cold and barren land.

Toponymy can be quite entertaining. Many toponyms have fascinating historical stories behind them or reflect amusing cultural practices (well, amusing to some of us). Many toponyms have historical legacies that are inappropriate or offensive, by modern standards; geographer Mark Monmonier discusses these in his amusing 2006 book, From Squaw Tit to Whorehouse Meadow: How Maps Name, Claim, and Inflame. Some of the most fun you can have with toponyms is reading about the very long ones. A lake in Massachusetts is claimed to be the longest toponym in the U.S., at 45 letters long: Chargoggagoggmanchauggagoggchaubunagungamaugg. A town in Wales has that beat at 58 letters, and it’s really hard to pronounce if you’re not a Welsh speaker: Llanfairpwllgwyngyllgogerychwyrndrobwllllantysiliogogogoch. But the Maori people of New Zealand have that beat, naming a hill with an 85-letter appellation: Taumatawhakatangihangakoauauotamateaturipukakapikimaungahoronukupokaiwhenuakitanatahu. (And the hill is only a thousand meters in elevation!) Perhaps the world champion is the full official name of a city in Thailand, at 111 letters, grouped into 6 words (there are other versions of the full name): Krungthephphramahanakhon Bowonratanakosin Mahintharayuthaya Mahadilokphiphobnovpharad Radchataniburirom Udomsantisug. Luckily for us, it’s also known informally as simply Bangkok.

Toponymy is not just a scholarly pursuit for geographers, historians, linguists, and folklorists. It has great meaning and significance for lay people as well. In a sense, naming expresses ownership, because it implies both comprehension and the legitimacy of the namer’s historical and cultural legacy. Hence, colonizers and claimants to territory usually change toponyms, and the original owners usually change them back if and when they get a chance. The Congo Free State became the Belgian Congo became Zaire. It is currently the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The Soviets changed the name of the city of St. Petersburg to Petrograd and then to Leningrad; the Russian Federation has changed it back to St. Petersburg. A fascinating example is the name of the tallest peak in North America. In 1896, the peak known as Denali to indigenous residents was renamed Mt. McKinley by the U.S. government; a national park of the same name was created in 1917. In 1975, the Alaska state government changed the name of the mountain back to Denali, but the U.S. Board on Geographic Names (more below) never consented to this, and still called it Mt. McKinley. In 1980, however, the federal government did change the name of the park to Denali.

Recording and updating toponyms has always been of practical importance as well. With the advent of digital “gazetteers” (place-name indexes and atlases) and automated mapping and routing systems, this is probably even more important. There are often multiple place names, multiple spellings, official names and local names, and places named in multiple languages. Some places are as yet unnamed but become important in information systems. But consistent or mutually translatable toponyms are crucial for navigation, military activity, scientific study, economic development, tourism, postal services, government, education, and more. Recognizing this problem, President Harrison established the U.S. Board on Geographic Names in 1890, under the auspices of the U.S. Geographical (oops, Geological) Survey. It was the first government agency for toponym standardization in the world. (As staid and bureaucratic as the agency sounds, we can presumably offer kudos to the person who managed to get the Board to accept a beach named Sunova.) More recently, the United Nations started its own geographic names program.

Keith Clarke took the following questions and answers from the Ask Dr. Map web site. Launched in 2004, the site has wowed the world of Cartography ever since. This repository of esoteric map ephemera (also known as “mapcrap” by aficionados) addresses everything from the definition of a “cartophilatelist” to the rumor that Waldo Tobler used to receive mail addressed to the latitude and longitude of his home and, of course, to the subject of toponymy:

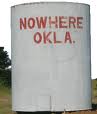

Dear Dr. Map: Is nowhere somewhere? There is only one “official” listed “populated place” in the United States called Nowhere. The place is in Caddo County, Oklahoma (35 deg 09 min 33 sec N 98 deg 26 min 31 sec W), at the South East end of Fort Cobb Reservoir, 9 km from Albert, OK. The small cluster of buildings with only a few residents and one store was named in the 1970s by a California couple, who together opened a boathouse there. The husband, bugged by his wife for moving them to the middle of nowhere, painted “NOWHERE, OKLA” in big red letters on a water tank. When the current owner bought the property in 1979, he kept the name and converted the boathouse into a much-photographed convenience store. If you are driving, you need the intersection of E1280 Road and N2550 Road. So yes, even Nowhere is somewhere!

Dear Dr. Map, What are some of the strangest place names in the United States? Toponymy is the system of names by which places are known. There is an extraordinarily large number of named features in the United States. The names as they appear on United States Geological Survey maps are contained in a data base, the Geographic Names Information System. The U.S. Board on Geographic Names, which dates back to 1890, is charged with naming and renaming features in the United States. The data base is a source of immense Inspiration (Arizona). Some, you just want to Jot ‘Em Down (Texas). What Cheer (Iowa) and Joy (Illinois, Ohio, W. Virginia, Texas, Oklahoma, and more) there is in discussing the Ding Dong (Texas) world of Why (Arizona) placenames are so Peculiar (Missouri). Dr. Map could go on at length, but instead recommends a book by David Jouris entitled All over the Map: An Extraordinary Atlas of the United States (Ten Speed Press, 1994). So I finish with a few favorites: Bumble Bee , Arizona; Horseheads , New York; Experiment , Georgia; Hell , Michigan, and Nameless, Tennessee. Dr. Map also wonders what it would be like to receive a latitude-longitude postcard, bearing a stamp showing a map, postmarked Lost Nation (Iowa).

Dear Dr. Map, What is a good example of a “toponymic blunder?” Toponymy is the study of the names by which geographical places are known. Cartographers have to deal not only with making sure that a place name is correct, but also with what places to select for labeling, and with choosing how to label them on a map. A first-rate example of a toponymic blunder was highlighted during the Eighth United Nations Conference in the Standardization of Geographical Names, and was contributed by A. V. Buren, et at. Apparently, inspired western surveyors in Arab countries who interrogated locals for place names often received the reply “mush arif” (“I don’t know”). This was then dutifully recorded on maps, making the term a frequently occurring Arabic place name. An example is “As Musharifa” (A high place) on the British Survey of Palestine 1:100,000, Sheet 3, 1937. Makes you wonder how many other toponymic blunders there are out there.