“The inhabitants of Easter Island consumed a diet that was lacking in seafood and was, literally, quite ratty.” Owen Jarus, writing for Livescience.com, points out the implications in an article titled “Diet of Easter Islanders Revealed: Rats!”:

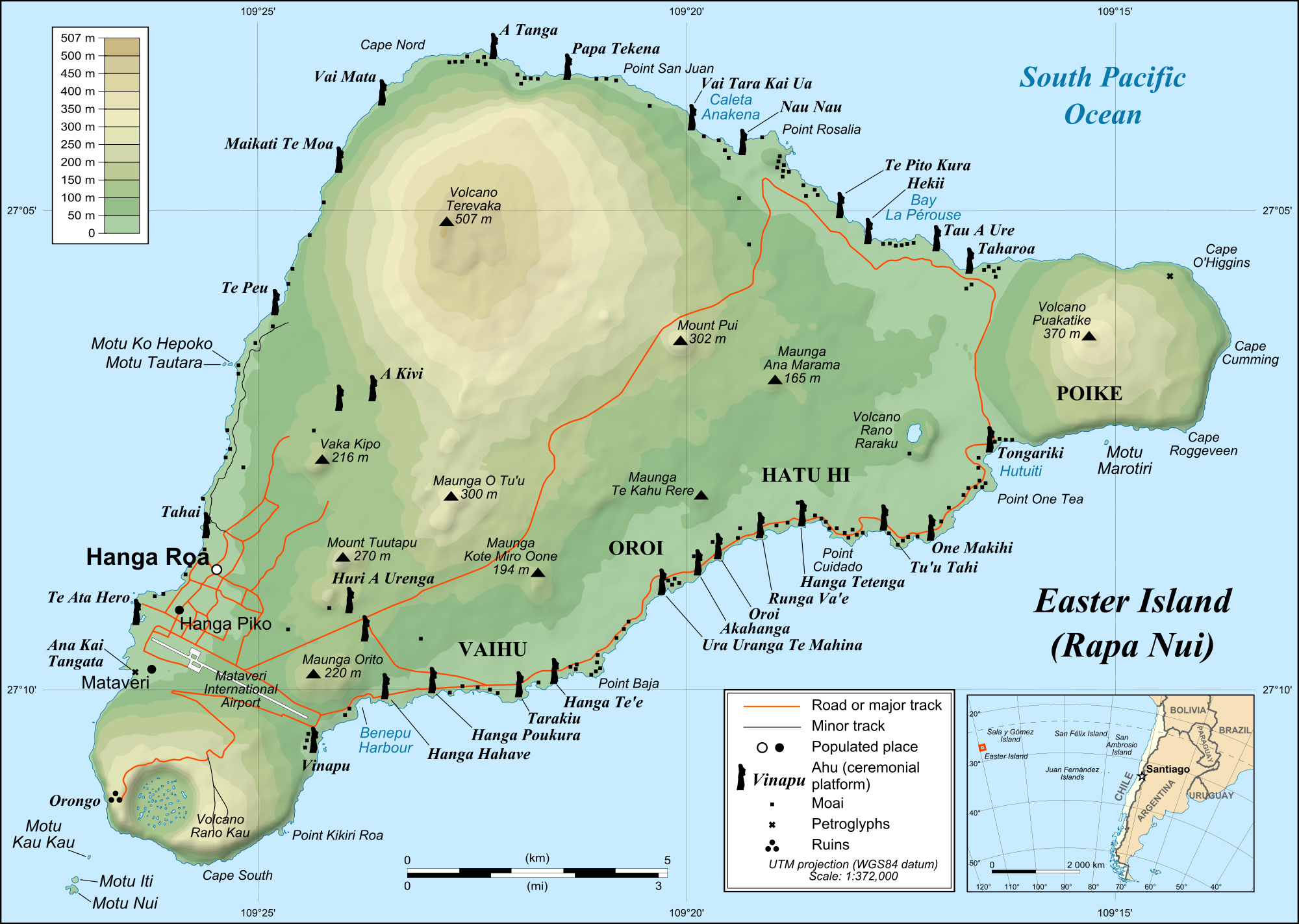

The island, also called Rapa Nui, first settled around A.D. 1200, is famous for its more than 1,000 “walking” Moai statues, most of which originally faced inland. Located in the South Pacific, Rapa Nui is the most isolated inhabited landmass on Earth; the closest inhabitants are located on the Pitcairn Islands about 1,200 miles (1,900 kilometers) to the west.

To determine the diet of its past inhabitants, researchers analyzed the nitrogen and carbon isotopes, or atoms of an element with different numbers of neutrons, from the teeth (specifically the dentin) of 41 individuals whose skeletons had been previously excavated on the island. To get an idea of what the islanders ate before dying, the researchers then compared the isotope values with those of animal bones excavated from the island.

Additionally, the researchers were able to radiocarbon date 26 of the teeth remains, allowing them to plot how the diet on the island changed over time. Radiocarbon dating works by measuring the decay of carbon-14 allowing a date range to be assigned to each individual; it’s a method commonly used in archaeology on organic material. The research was published recently online in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology.

The researchers found that throughout time, the people on the island consumed a diet that was mainly terrestrial. In fact, in the first few centuries of the island’s history (up to about A.D. 1650) some individuals used Polynesian rats (also known as kiore) as their main source of protein. The rat is somewhat smaller than European rats and, according to ethnographic accounts, tasty to eat.” Our results indicate that contrary to previous zooarchaeological studies, diet was predominantly terrestrial throughout the entire sequence of occupation, with reliance on rats, chickens and C3 plants,” the researchers write in their journal article, noting that the resources from C3 plants (or those that use typical photosynthesis to make sugars) would have included yams, sweet potatoes and bananas.

The islanders’ use of rats was not surprising to the researchers. Archaeological excavations show the presence of the Polynesian rat across the Pacific. The Polynesian form commonly travels with humans on ocean voyages and, like any other rat, multiplies rapidly when it arrives on a new island. In some cases, the rats were probably transported intentionally to be used as food, something supported by ethnographic accounts stating that, in some areas of Polynesia, rats were being consumed at the time of European contact. Additionally, previous research has suggested the rats were at least partly responsible for the deforestation of Rapa Nui (source).

According to ethnologist Barbara A. West, “Sometime before the arrival of Europeans on Easter Island, the Rapanui experienced a tremendous upheaval in their social system brought about by a change in their island’s ecology… By the time of European arrival in 1722, the island’s population had dropped to 2,000–3,000 from a high of approximately 15,000 just a century earlier.” By that time, 21 species of trees and all species of land birds went extinct through some combination of overharvesting/overhunting, rat predation, and climate change, the island was largely deforested, and it did not have any trees more than 10 feet tall. Loss of large trees meant that residents were no longer able to build seaworthy vessels, significantly diminishing their fishing abilities. This was further exacerbated by the loss of land birds and the collapse in seabird populations. By the 18th century, residents of the island were largely sustained by farming, with domestic chickens as the primary source of protein” (Wikipedia: Easter Island).

Research by Anthropology Professor Terry Hunt of the University of Hawai’i at Manoa points out that the island had a relatively simple ecosystem with vegetation once dominated by millions of palms. The original ecosystem of the island, with a limited range of plants, and few if any predators, would…have been particularly vulnerable to alien invasions. Almost all of the palm seed shells discovered on the island were found to have been gnawed by rats. Thousands of rat bones have been found, and crucially, much of the damage to forestry appears to have been done before evidence of fires on the island. Evidence from other Pacific islands also confirms how devastating rats can be.

Exactly how rats got on to the island is not known, although one theory is that they arrived as stowaways in the first canoes of Polynesian colonists. Once they arrived, the rats found palm nuts offered an almost unlimited high-quality food supply. Under ideal conditions, rats reproduce so rapidly that their numbers double every 47 days; unchecked, a single mating pair can produce a population of nearly 17 million in just over three years. Research in the Northwest Hawaiian Islands shows that when available food is taken into account, populations can reach 75 to the acre. “At 75 rats per acre, the rat population of Easter Island could have exceeded 3.1 million.”

The Hawaiian research demonstrates that rats were capable, on their own, of deforesting large lowland coastal areas in about 200 years or less. “In the absence of effective predators, rats alone could eventually result in deforestation” (source; also see “Rethinking the Fall of Easter Island”).

Article by Bill Norrington