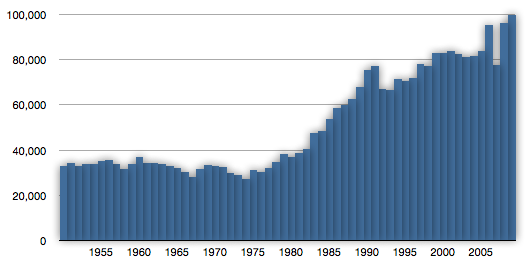

Scarcity and fashion have a lot to do with perceived value. Lobsters, like salmon and oysters, are an acquired taste and were once so commonplace that they were disdained as food only fit for lower members of society. Today, lobsters are still relatively commonplace—lobster catches have quadrupled over the last 20 years—but they’re a lot more popular.

“In North America, the American lobster did not achieve popularity until the mid-19th century, when New Yorkers and Bostonians developed a taste for it, and commercial lobster fisheries only flourished after the development of the lobster smack, a custom-made boat with open holding wells on the deck to keep the lobsters alive during transport. Prior to this time, lobster was considered a mark of poverty or as a food for indentured servants or lower members of society in Maine, Massachusetts, and the Canadian Maritimes, and servants specified in employment agreements that they would not eat lobster more than twice per week. Lobster was also commonly served in prisons, much to the displeasure of inmates. American lobster was initially deemed worthy only of being used as fertilizer or fish bait, and it was not until well into the twentieth century that it was viewed as more than a low-priced canned staple food” (source).

So why the change in fashion? A lot of it has to do with improved methods of catching, processing, and presenting lobsters. Live lobsters fetch the highest prices, and ironically, the best tasting ones are the cheapest. “Caught lobsters are graded as new-shell, hard-shell, or old-shell, and because lobsters which have recently shed their shells are the most delicate, there is an inverse relationship between the price of American lobster and its flavor. New-shell lobsters have paper-thin shells and a worse meat-to-shell ratio, but the meat is very sweet. However, the lobsters are so delicate that even transport to Boston almost kills them, making the market for new-shell lobsters strictly local to the fishing towns where they are offloaded. Hard-shell lobsters with firm shells, but with less sweet meat, can survive shipping to Boston, New York, and even Los Angeles, so they command a higher price than new-shell lobsters. Meanwhile, old-shell lobsters, which have not shed since the previous season and have a coarser flavor, can be air-shipped anywhere in the world and arrive alive, making them the most expensive. One seafood guide notes that an eight-dollar lobster dinner at a restaurant overlooking fishing piers in Maine is consistently delicious, while ‘the eighty-dollar lobster in a three-star Paris restaurant is apt to be as much about presentation as flavor’” (Ibid.).

If someone hybridized a blue dandelion, it would fetch big money from garden enthusiasts. On a similar note, a blue lobster is a rarity that usually ends up as a prize specimen in an aquarium rather than in a cooking pot. “The normal coloration of Homarus americanus is dark bluish green to greenish brown, redder on the body and claws, and greener on the legs. This coloration is produced by mixing yellow, blue, and red pigments. An estimated one in 2 million lobsters are blue. A genetic mutation causes a blue lobster to produce an excessive amount of a particular protein. The protein and a red carotenoid molecule known as astaxanthin combine to form a blue complex known as crustacyanin, giving the lobster its blue color. Yellow lobsters are the result of a rare genetic mutation and the odds of finding one are estimated to be 1 in 30 million.”

“In July 2010, an albino lobster was reportedly caught in Gloucester. It is estimated that only one in 100 million lobsters is albino — lacking in colored pigments. On August 28, 2010, a calico lobster with a mottled orange and black shell was reported to have been caught in Maine. Only albino lobsters are rarer, and orange lobsters such as these are a 1 in 30 million catch.”

“Several lobsters have been caught with different colorings on their left and right halves. For instance, on July 13, 2006, a Maine fisherman caught a brown and orange lobster, and submitted it to the local oceanarium, which had only seen three lobsters of this kind in 35 years. The chance of finding one is estimated at 1 in 50 million. Many split-colored lobsters observed have been hermaphroditic chimeras, but not all.” (source).

Despite the rarity of strangely colored lobsters, many more of them are reported being caught in recent years. It is unclear as to whether this is because cellphones and social media make it easier to report such catches, if it is due to a drop in predator populations (cod, in particular) which had an easier job spotting oddly colored lobsters, or if it is simply because a lot more lobsters are being caught these days. Either way, they all taste like “normal” lobsters, and, except for albinos which have no pigment, they all turn red when they’re cooked. By the way, the odds of catching a live red lobster are 1 in 10 million.

Article by Bill Norrington