“For more than five hundred years, the envoys of civilization sailed through storms and hacked through jungles, startling in turn one tribe after another of long-lost human cousins. For an instant, before the inevitable breaking of faith, the two groups would face each other, staring – as innocent, both of them, as children, and blameless as if the world had been born afresh.

To live such a moment seems, when we think of it now, to have been one of the most profound experiences that our planet in its vanished immensity once offered. But each time the moment repeated itself on each fresh beach, there was one less island to be found, one less chance to start everything anew. It began to repeat itself less and less often, until there came a time, maybe a century ago, when there were only a few such places left, only a few doors still unopened.

Sometime quite recently, the last door opened. I believe it happened not long before the end of the millennium, on an island already all but known, a place encircled by the buzzing, thrumming web of a world still unknown to it, and by the mesh of a history that had forever been drawing closer” (Adam Goodheart, The last island of the savages, The American Scholar, Autumn 2000, 69(4):13-44).

In ~1296, Marco Polo described them (second hand–he never saw them) as “a most brutish and savage race, having heads, eyes, and teeth like those of dogs. They are very cruel, and kill and eat every foreigner whom they can lay their hands upon.” In 1771, an East India vessel passed by their island and sighted “a multitude of lights … upon the shore” – the first recorded mention of their island. In 1867, an Indian merchantman was wrecked on the reef of the island, and the 86 passengers and 20 crewmen made it safely to shore, whereupon the islanders attacked them with bows and arrows (the Royal British Navy rescued the ship’s company several days later but could find no sign of the attackers). In 1896, an escaped Hindu convict landed on the beach of the island; a search party later found his body, pierced by several arrows and with its throat cut.

There were no further recorded encounters with them until, in 1974, the island was visited by a film crew that was shooting a documentary titled Man in Search of Man; the natives fired arrows at them, one of which hit the film director in the thigh. In 1981, a Panamanian-registered freighter ran aground on their island, and the crew was attacked by the islanders; the Indian Navy had to send a tugboat and a helicopter to rescue the besieged sailors. In 1991, an Indian government anthropologist made the “first friendly encounter” with them, but only after 20 years of unsuccessful attempts. Jacques Cousteau once tried to shoot a documentary on the islands but was chased away. Shortly after the disastrous 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, the Indian government sent a helicopter to ascertain the survival of the islanders who proceeded to shoot arrows at the hovering aircraft to repel it. In 2006, they killed two fishermen who were fishing illegally within range of the island and drove off the helicopter that was sent to retrieve their bodies with a hail of arrows; the bodies were never recovered.

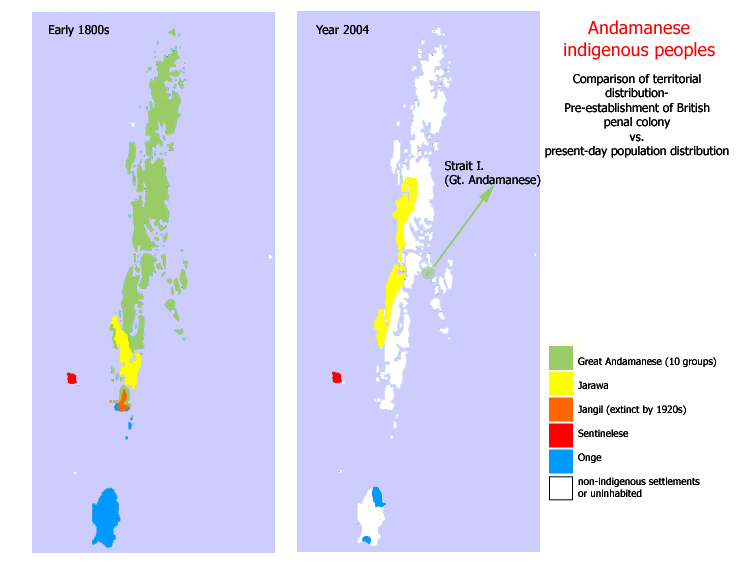

“The Sentinelese (also Sentineli, Senteneli, Sentenelese, North Sentinel Islanders) are one of the Andamanese indigenous peoples of the Andaman Islands, located in the Bay of Bengal. They inhabit North Sentinel Island which lies westward off the southern tip of the Great Andaman archipelago. They are noted for vigorously resisting attempts at contact by outsiders. As a result, they may be the most socially isolated people on Earth” (Wikipedia).

“North Sentinel Island is one of the Andaman Islands in the Bay of Bengal. It lies to the west of the southern part of South Andaman Island, and has an area of 72 km². Officially the island is administered by India as part of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands Union Territory (since 1947). Because there has never been any treaty with the people of the island, nor any record of a physical occupation whereby the people of the island have conceded sovereignty, the island exists in a curious state of limbo under established international law and can be seen as a sovereign entity under Indian protection. It is, therefore, one of the de facto autonomous regions of India.

From 1967 on, the Indian authorities in Port Blair embarked on a limited program of attempts at contacting the Sentinelese, under the auspices of the Director of Tribal Welfare and anthropologist T. N. Pandit. These “Contact Expeditions” consisted of a series of planned visits which would progressively leave “gifts”, such as coconuts, on the shores, in an attempt to coax the Sentinelese from their hostile reception of outsiders. For a while these seemed to have some limited success; however the program was discontinued in the late 1990s following a series of hostile encounters resulting in several deaths in a similar program practiced with the Jarawa people of South and Middle Andaman Islands and because of the danger of introducing diseases” (Wikipedia).

T. N. Pandit, the anthropologist credited with the “first friendly encounter” with the Sentinelese in 1991 (after 20 years of unsuccessful attempts) is quoted as stating, “That they voluntarily came forward to meet us – it was unbelievable. They must have come to a decision that the time had come. It could not have happened on the spur of the moment. But there was this feeling of sadness also – I did feel it. And there was the feeling that at a larger scale of human history, these people who were holding back, holding on, ultimately had to yield.

It’s like an era in history gone. The islands have gone. Until the other day, the Sentinelese were holding the flag, unknown to themselves. They were being heroes. But they have also given up. They would not have survived forever – that, I can reason out. On a scientific basis, we can say that this population might have lived for another hundred years, but eventually. . . Even destruction takes place in the natural course of things; no one can help it, it happens. But here we have been doing it in a very conscious way, knowing full well what the consequences could be. What would be and what could be are the same” (Goodheart, Ibid.).

Article by Bill Norrington. If this subject matter caught your imagination, I suggest that you read Goodheart’s full text, as well as the novel “At Play in the Fields of the Lord” by Peter Matthiessen (Vintage, 1983).