They’re considered a culinary delicacy by some people, they symbolize summer and re-birth in literature, they only appear every 13 years, their mating calls can be deafening, and they’re emerging in huge numbers across the southern U.S. at this very moment. Yep, we’re talking about periodical cicadas, specifically, the “Great Southern Brood” of Cicadidae Magicicada.

Commonly known as 13-year locusts, 13-year cicadas are actually in the Order Hemiptera and are related to leaf hoppers and spittlebugs, not locusts or grasshoppers (Order Orthoptera). There are seven species of periodical cicadas in the genus Magicicada, four with 13-year life cycles and three with 17-year cycles, and they are found only in eastern North America. They live underground as larvae and then synchronously emerge in massive numbers (sometimes more than 1.5 million individuals per acre) and transform into adults either every 13 or 17 years. The genus is subdivided into species and subspecies according to the life cycle of each “brood.” Brood XIX, the Great Southern Brood, is the largest and most geographically widespread of all the 13-year cicada broods, and they are what the current fuss is all about.

“After years of living in underground tunnels, thousands of periodical cicadas emerge from the earth, as if by a predetermined signal, shed their nymphal skins, and spread out through the nearby trees and bushes. Up to 40,000 can emerge from a under a single tree! The cicada’s precise but prolonged time schedule revolves around survival for the masses. When a large population of juicy insects appears on the scene, predators make the most of the situation, but simply cannot eat all the insects. Thus, a significant number of cicadas live to reproduce. Long-lived predators may actually remember the feast and return to the scene in subsequent years. Short-lived predators, being well fed from the cicada banquet, reproduce successfully and often leave a larger population to await next year’s emergence. However, ‘next year’ doesn’t happen for at least 13 years, so the periodical cicada is able to outlast and escape most of its enemies.

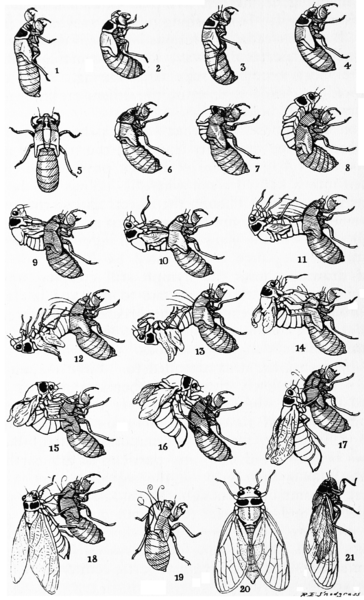

Periodical cicadas spend 13 or 17 years buried 18 to 24 inches deep in the soil of wooded and forested areas feeding on sap from tree roots. They dig their way out of the soil during late May and June and climb up tree trunks, posts, and poles to molt into adults. The adult insect is about 1.5 inches long with a black body, red legs, and red eyes. They have piercing and sucking mouthparts and will feed on a variety of woody vegetation. Each adult may live five or six weeks. They will mate and the female will pump her egg into slits of small twigs and shrubs, using her sickle-like ovipositor. This will cause some twig dieback, called flagging, but has no long-term consequences to the tree. The eggs will hatch after six to seven weeks and the newly hatched nymphs (about the size of an ant) fall to the ground and burrow until they find a suitable tree root, where they settle down to feed and wait. The nymphs will undergo five molts in their 13 or 17 years” (source).

“The last time the Great Southern Brood of 13-year cicadas came out was in 1998; this year’s brood of adults will procreate and die out by mid June, and the next generation won’t emerge until 2024. Adult periodical cicadas live only for a few weeks, and their short adult life has one purpose: reproduction. The males ‘sing’ a mating song; like other cicadas, they produce loud sounds using their tymbals. Receptive females respond to the calls of conspecific males with timed wing-flicks, which attract the males for mating. The sounds of a ‘chorus’—a group of males—can be deafening and reach 100 decibels” (source).

Soon to die / yet no sign of it / in the cicada’s chirp – Haiku by Matsuo Kinsaku (1644-1694), the most famous poet of the Edo period in Japan.

Cicadas are the sound of summer, of the year when you were young. . . . It’s the closest thing to a time machine you can get outside science fiction – Robert J. Thompson, a professor of popular culture at Syracuse University.