The ginkgo tree, Ginkgo biloba, is a living fossil—the oldest tree species known to man—dating back 150 million years when several species of the family Ginkgophyta flourished in temperate zones of the world. It’s related to gymnosperms (conifers) but is classified in its own division of Ginkgophyta and is the only living species within this ancient botanical group. Once thought to be extinct, the ginkgo was “rediscovered” in China by European botanists in the 18th century and is now a prized landscape feature in many parts of the world. It’s a deciduous tree that is extremely hardy, can live over 500 years, and can attain a height of over 100 feet and a width of up to 30 feet. Extracts made from the leaves contain compounds that are used as herbal remedies for senility and poor circulation, and the seeds are a popular food item throughout Asia. Ginkgos are dioecious (i.e., have male and female plants), and the fruit of the female ginkgo has such a foul odor that female ginkgos have been banned in some Western urban areas.

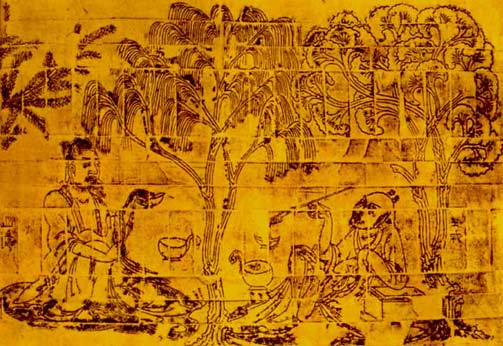

The name “ginkgo” is derived from the Japanese word ginkyo or “silver apricot,” referring to the fruit, and “biloba” (or “two-lobed”) refers to the ginkgo’s characteristic fan-shaped leaves. The leaves supposedly resemble those of a maidenhair fern, hence the nickname of maidenhair tree (though that lexicography is disputed). These distinctive leaves are depicted on Chinese silk paintings and relief murals from the fifth century AD, family crests incorporating them have been used since the Middle Ages in Japan, and they became a motif used widely by European Art Nouveau practitioners.

So what’s this got to do with Geography? Well, to start with, there’s a magnificent specimen of a male ginkgo tree alongside the north wing of Ellison Hall (by EH 1629), whose leaves turn a beautiful pale gold in the fall. More to the point, the ginkgo has attracted a great deal of multidisciplinary study by archeologists, botanists, linguists, art historians, pharmacologists, taxonomists, students of literature, and (gasp!) even geographers—you can even buy a “Ginkgo Tree-to-be Kit” from the National Geographic Online Store. Besides, it was a favorite tree of Frank Lloyd Wright. Not to mention the fact that your editor is also a living fossil and could use a remedy for senility. If you’d like to know more about this intriguing tree, see “The Ginkgo Pages” at http://www.xs4all.nl/~kwanten/.

Ginkgo Biloba

In my garden’s care and favour/From the East this tree’s leaf shows/Secret sense for us to savour/And uplifts the one who knows.

Is it but one being single/Which as same itself divides?/Are there two which choose to mingle/So that each as one now hides?

As the answer to such question/I have found a sense that’s true:/Is it not my songs’ suggestion/That I’m one and also two?

(Goethe, 1815. From: Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Poems of the West and East. Verse Translation by John Whaley, Peter Lang, Berne, 1998, pp. 260-261).

Article by Bill Norrington