“The heavily consumed confectionery known as chocolate comes at a heavy price. Chocolate slavery today is wide spread in West African countries such as Mali, the Ivory Coast, Cameroon, Ghana, and Nigeria. 90% of the chocolate labor force is young children either kidnapped from their home lands, or sold into slavery, robbing them of their freedom and chance for education. In Mali, children are bought and sold for $30 in U.S currency from poor areas. Most of the time, poor parents from slums sell their own sons and daughters into slavery to make a quick profit and to decrease the number of mouths to feed. More than 109,000 children toil in cocoa fields under the worst conditions. On a daily basis they deal with long hours, hot temperatures, dangerous tools, and poisonous pesticides” (source).

“In an era of mechanized agriculture, growing and harvesting cacao is still a labor intensive practice. Although chocolate is a huge ($74 billion annually) global business, only about 6-8 percent of this revenue actually makes its way back to the cocoa farmers, many of whom run small family operations. Labor abuse is said to be rife in some cocoa regions, and reports of farmers enslaving thousands of child workers in places like Côte d’Ivoire have sparked widespread criticism of the industry. Labor and environmental issues have inspired the formation of such organizations as the Fair Trade Federation, Rainforest Alliance and Equal Exchange. These are associations of wholesalers, retailers, and producers whose members are committed to growing cacao sustainably, and providing fair wages and good employment opportunities to economically disadvantaged artisans and farmers worldwide. Consumers can help in this effort by choosing chocolates that are organic and carry a “fair trade” label (source).

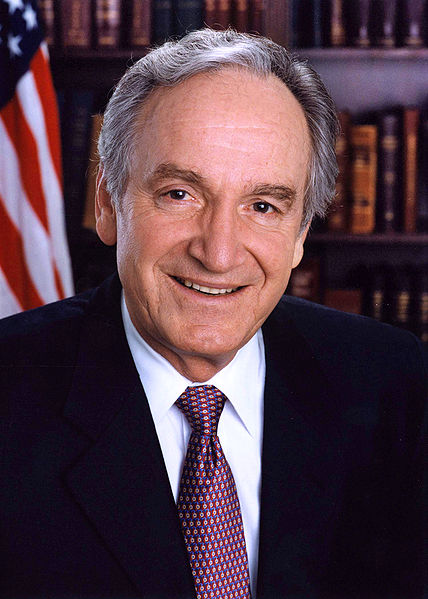

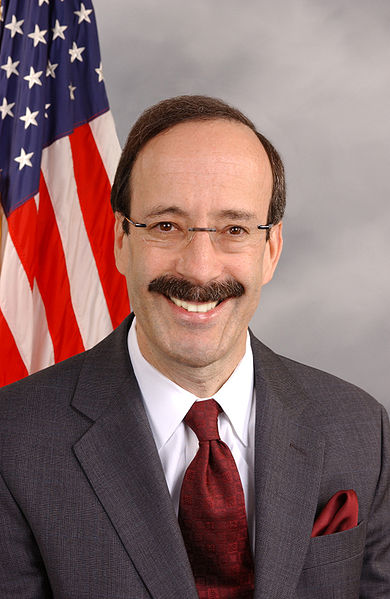

“The Harkin-Engel Protocol, commonly referred to as the Cocoa Protocol, is an international agreement aimed at ending child labor in the production of cocoa. It was signed in September 2001. The Protocol was hailed as a framework for progress, bringing together industry, West African governments, organized labor, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), farmer groups and experts to raise labor standards. It was said to mark a first – an international industry taking responsibility for addressing labor abuses in its supply chain. However, the protocol was criticized by some, criticism which seems to have been validated by the fact that industry still has not delivered on farm level certification against the worst forms of child labour.

The joint foundation was established, known as the International Cocoa Initiative. Through this foundation, $3 million was spent on pilot projects. In addition, individual companies started their own initiatives. An industry-funded Verification Working Group was begun in 2004. The Protocol stipulated that by July 2005, the chocolate industry would develop standards of certification. This deadline was not met. An extension of the Protocol was agreed upon, giving industry 3 more years to implement the Protocol. Again, after 3 more years, the key promises of the Protocol have not been met. The International Labor Rights Fund then filed a lawsuit against Nestle, Cargill and Archer Daniels Midland. It was filed in July 2005 under the Alien Tort Claims Act on behalf of a class of Malian children who were trafficked into Côte d’Ivoire and forced to work on cocoa farms for twelve to fourteen hours a day with no pay, little food and sleep, and frequent beatings. Funding for the Verification Working Group was discontinued in 2006. However, in Summer 2007, the manufacturers contracted another company to fulfill this function” (source).

“The industry’s evident lack of compliance with Harkin-Engel puts everyone involved in a difficult position. New coercive legislation requiring “child-labor-free” labeling could cause trouble for the large cocoa exporters and chocolate manufacturers if there were boycotts of non-labeled chocolate. But impoverished farmers in Ivory Coast say loss of markets would also hurt them and their children. Since the idea was first floated in 2001, the chocolate industry has taken the same position: Labeling “would hurt the people it is intended to help,” says Susan Smith, a spokeswoman for the Chocolate Manufacturers Association and the World Cocoa Foundation.

There is fair-trade chocolate on the market, but it accounts for no more than 1 percent of global supply – and the movement has little traction in Ivory Coast. A more effective way to combat child labor would be for the government of Ivory Coast to invest some of the revenue it gets from high taxes on cocoa exporters in education and social services to help poor farmers. But the government of Ivory Coast is ranked among the most corrupt in the world by Transparency International, a nongovernmental watchdog group. And it seems happier making excuses than changes” (Source).

Article by Bill Norrington