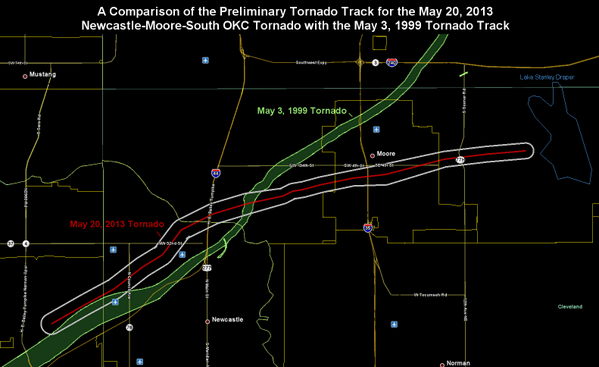

“The 2013 Moore tornado was a violent tornado that occurred on the afternoon of May 20, 2013. The EF5 [the Enhanced Fujita scale] rates the strength of tornadoes in the United States and Canada, based on the damage they cause. A tornado with winds estimated at 210 miles per hour (340 km/h) impacted Moore, Oklahoma, and adjacent areas, killing at least 24 people, including 9 children, and injuring more than 240 others…The tornado was part of a larger weather system that had produced several other tornadoes over the previous two days. The tornado touched down at 2:45 p.m. CDT (19:45 UTC) west of Newcastle, staying on the ground for approximately 50 minutes over a 17-mile (27 km) path, crossing through a heavily populated section of Moore. The tornado was 1.3 miles (2.1 km) wide at its peak.

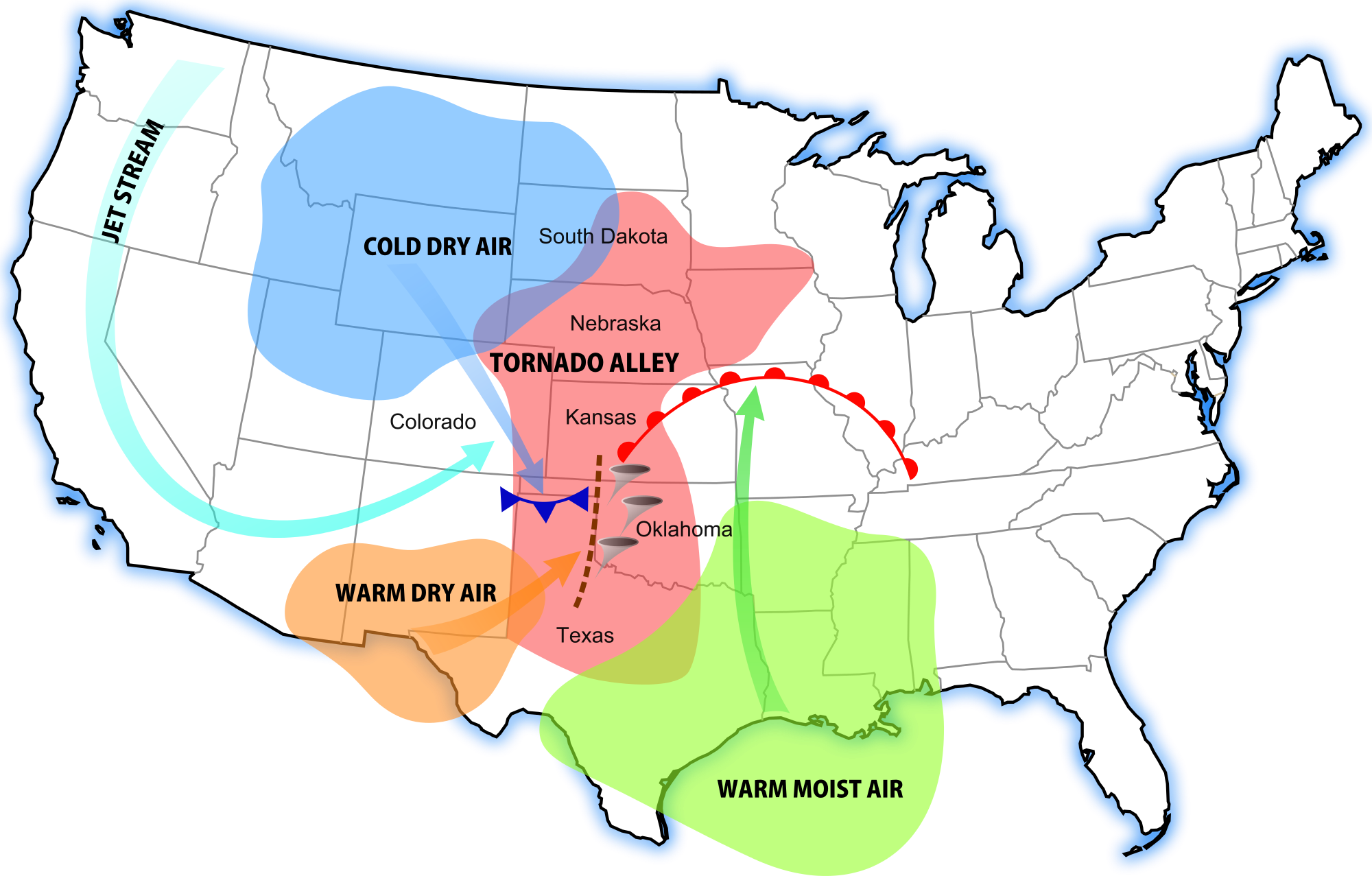

On May 20, a prominent central upper trough moved eastward with a lead upper low pivoting over the Dakotas and Upper Midwest region. A Southern stream shortwave trough and a moderately strong polar jet moved east-northeastward over the southern Rockies to the southern Great Plains and Ozarks area, with severe thunderstorms forming during the peak hours of high temperatures. With the influence of moderately strong cyclonic flow aloft, the air mass was expected to become unstable across much of the southern Great Plains, Ozarks, and middle Mississippi Valley by the afternoon. Dewpoints in the mid to upper 60s °F and some lower 70s °F were common within a broad warm sector ahead of a cold front extending from an eastern Dakota surface low southwestward to near the Kansas City area and western Oklahoma, and ahead of a dry line extending from southwest Oklahoma southward into western north and west-central Texas. The National Weather Service issued a warning 16 minutes before the tornado hit – 3 minutes earlier than average. The area affected is located in Tornado Alley, a colloquial term for the area of the United States where tornadoes are most frequent.

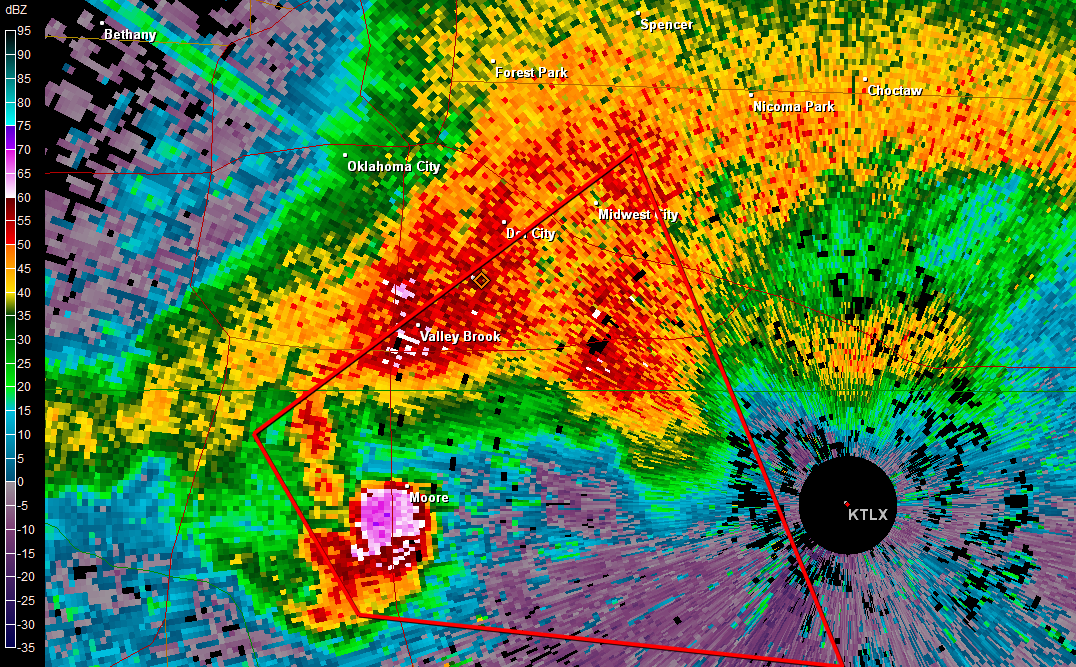

At 2:40 p.m. CDT, a tornado warning was issued on a severe thunderstorm approaching the Oklahoma City metropolitan area. At 2:45 p.m. CDT, an EF0 tornado touched down roughly 4.4 mi (7.1 km) west of Newcastle in Grady County. Tracking northeast, the system rapidly intensified, attaining EF4 intensity within ten minutes of touching down. By 3:01 p.m. CDT, a second more strongly worded warning was issued for the area. A tornado emergency was declared for southern Oklahoma City and Moore as storm spotters confirmed a large and violent tornado approaching the area. After crossing the Interstate 44 Bridge over the Canadian River, the tornado turned east and tracked directly through Moore…The storm abruptly dissipated about 4.8 mi (7.7 km) east of Moore around 3:35 p.m. CDT. Overall, the tornado was on the ground for approximately 50 minutes along a 17 mi (27 km) track.

Most areas in the path of the storm suffered catastrophic damage. Entire subdivisions were obliterated and houses flattened in a large swath of the city. The Oklahoma Department of Emergency Management said about 2,400 homes were damaged and 10,000 people have been affected. Witnesses said it more closely resembled “a giant black wall of destruction” than a typical twister…With 24 fatalities, it was the deadliest U.S. tornado since the Joplin, Missouri tornado that killed 158 in 2011, according to the National Weather Service” (source; before and after photos here).

“Several meteorologists contacted by The Associated Press used real time measurements to calculate the energy released during the storm’s 40-minute life span. Their estimates ranged from 8 times to more than 600 times the power of the Hiroshima bomb, with more experts at the high end. Their calculations were based on energy measured in the air and then multiplied over the size and duration of the storm. An EF5 tornado has the most violent winds on Earth, more powerful than a hurricane. The strongest winds ever measured were the 302 mph reading, measured by radar, during the EF5 tornado that struck Moore on May 3, 1999, according to Jeff Masters, meteorology director at the Weather Underground.

It’s a combination of geography, meteorology, and lots of bad luck, experts said. ‘Tornadoes are perhaps the most difficult things to connect to climate change of any extreme,’ said NASA climate scientist Tony Del Genio. ‘Because we still don’t understand all the factors required to get a tornado’” (source).