The following is a ClimateCentral.org article by Brian Kahn, published February 12 2015, with the title above:

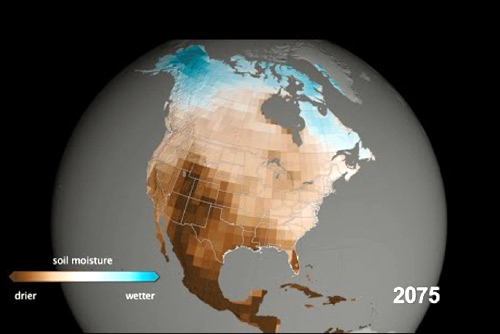

Climate change is creating an “unprecedented” risk of severe drought in the Southwest and Central Plains. Rising temperatures and decreasing rainfall mean that future drought could be more extreme than any drought seen in at least the past 1,000 years, and the effects could reverberate for urban dwellers and farmers across the regions.

The 1930s Dust Bowl created post-apocalyptic conditions for the Central Plains, but Lisa Graumlich, who heads the University of Washington’s College of the Environment, said that the severe drought that plagued the Southwest from 1100-1300, ”makes the Dust Bowl look like a picnic.” That drought occurred during what researchers have called the Medieval Climate Anomaly and contributed to widespread ecosystem shifts and the collapse of civilizations across the Southwest.

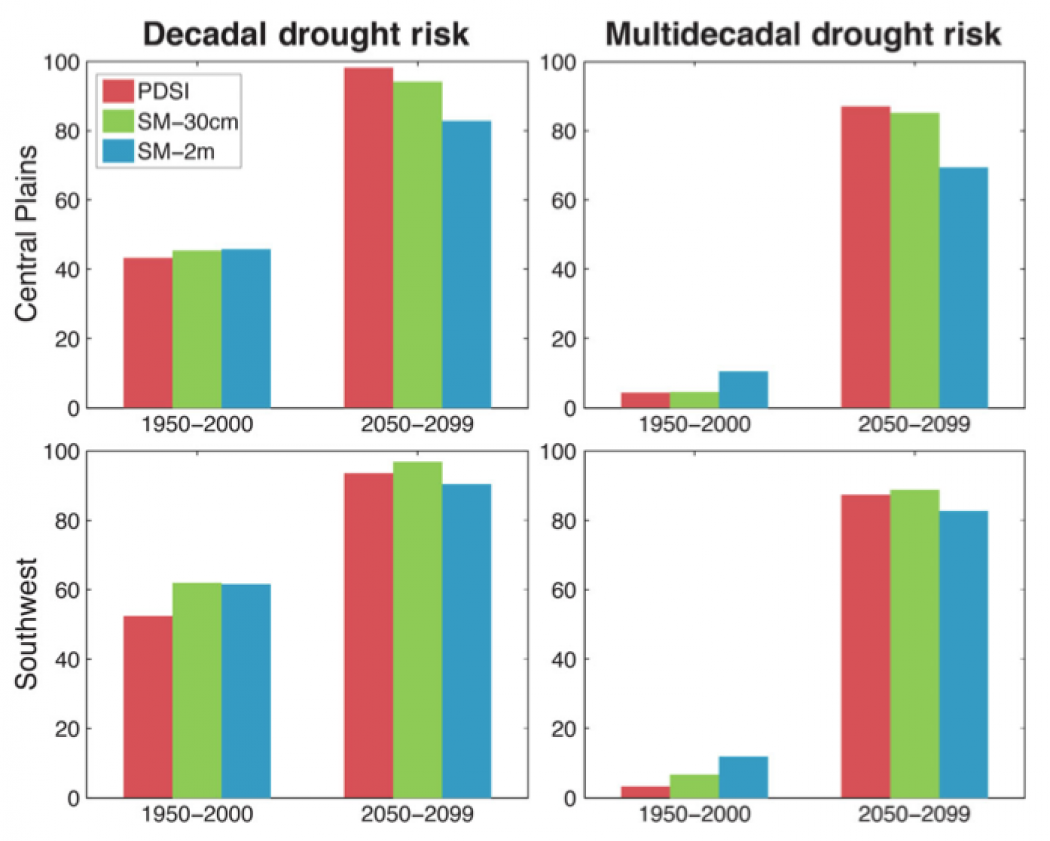

Yet both those droughts pale in comparison to the severity of drought projected to befall those regions — which encompass all or part of 17 states from California to Louisiana to Minnesota — during the latter half of the 21st century if greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise according to a new study published in Science Advances. Both regions are all but guaranteed to experience a severe drought that would last at least a decade, with the odds of a drought lasting multiple decades at about 80 percent. In comparison, the chance of a multidecadal drought occurring during 1950-2000 was less than 10 percent.

Previous studies have looked forward at drought risks and also drawn comparisons to the Dust Bowl, but none have drawn comparisons with tree ring records of the past. This one not only does that but uses a suite of 17 climate models and three drought measures to provide as much insight as possible.

“The surprising thing to us was really how consistent the response was over these regions, nearly regardless of what model we used or what soil moisture metric we looked at. It all showed this really, really significant drying,” Benjamin Cook, a researcher at the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies and lead author of the study, said.

The significance isn’t lost on Graumlich, who wasn’t affiliated with the study. “When they tell me we are headed to something like, or exceeding, the severity of the Medieval Climate Anomaly, the hair on my neck starts standing up. It’s very, very serious,” Graumlich said. Graumlich said that the drought during that period essentially dried up rivers east of the Sierra Nevada mountains and caused water levels at Mono Lake, an expansive inland lake in California, to virtually disappear. Highly evolved societies collapsed and descended into warfare. The Dust Bowl, though less severe in terms of drought and length, impacted a larger population. More than 3.5 million people abandoned the Plains in the 1930s as massive dust storms rolled over houses and fields, and heat baked the region.

Climate change is not only projected to dry out the western U.S. but also drive temperatures higher, which would help reinforce drought. That pattern is currently on display in California, where heat is helping keep dry conditions locked in place, according to research published late last year by Kevin Anchukaitis, a paleoclimatologist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute. Anchukaitis said the new study shows, “the increasing importance that higher temperatures and increased evaporative demand will have in fueling severe and persistent droughts.”

Technology and groundwater have helped insulate farmers from drought more than their Dust Bowl and Pueblo Indian counterparts. But the California drought has still cost the state at least $2.2 billion and thousands of jobs. And groundwater, which has been used to reduce the impacts somewhat, isn’t a renewable resource, at least not at the current rates of use.

That’s in part why future droughts in the Southwest and Central Plains could be even more costly. Agriculture in California, a nearly $43 billion industry, and grains produced in the Central Plains, including 40 percent of the world’s corn and about 10 percent of the world’s wheat, would both take big hits from any prolonged drought and could have a ripple effect felt beyond the region. Food supplies could be disrupted and price shocks could reverberate through global markets.

Growing populations in urban areas from Dallas to Minneapolis to Phoenix to Los Angeles could also face water shortages. “The work is well laid out, but it’s a tough paper to read given the implications, especially for someone who calls the Southwest home,” Jonathan Overpeck, director of the Institute of the Environment at the University of Arizona, said. “Impacts on water supply and natural land cover could be especially large in the Southwest, where warming is already exacerbating a 15-year long drought, and reservoir levels are already at all-time lows on the Colorado River.”

The study outlines the risk of drought using a few methods including the Palmer Drought Severity Index, which decision makers use to access federal emergency funds. Graumlich said that familiarity helps make this study more accessible to urban planners, water managers and agricultural services who will have to deal with an unfamiliar and sobering future.