The following is a News Release by the University of Zurich, dated July 25, 2013 and titled “Pigeons fly home with a map in their heads”:

It is a fascinating phenomenon that homing pigeons always find their way home. A doctoral student in biology at the University of Zurich has now carried out experiments proving that pigeons have a spatial map and thus possess cognitive capabilities. In unknown territories, they recognize where they are in relation to their loft and are able to choose their targets themselves.

Homing pigeons fly off from an unknown place in unfamiliar territory and still manage to find their way home. Their ability to find their way home has always been fascinating to us humans. Despite intensive research, it is not yet definitively clear where this unusual gift comes from. All we know is that homing pigeons and migratory birds determine their flight direction with the help of the Earth’s magnetic field, the stars and the position of the sun. As Nicole Blaser, a doctoral student in biology at the University of Zurich demonstrates in the Journal of Experimental Biology, homing pigeons navigate using a mental map (N. Blaser, G. Dell’Ariccia, G. Dell’Omo, D. P. Wolfer, and H.-P. Lipp. Testing cognitive navigation in unknown territories: homing pigeons choose different targets. Journal of Experimental Biology 216. July 24, 2013, doi: 10.1242/jeb.083246).

Research proposes two approaches to explain how homing pigeons can find their home loft when released from an unfamiliar place. The first version assumes that pigeons compare the coordinates of their current location with those of the home loft and then systematically reduce the difference between the two until they have brought the two points together. If this version is accurate, it would mean that pigeons navigate like flying robots. The second version accords the pigeons a spatial understanding and “knowledge” of their position in space relative to their home loft. This would presuppose a type of mental map in their brain and thus cognitive capabilities. Up until now, there has not been any clear evidence to support the two navigation variants proposed.

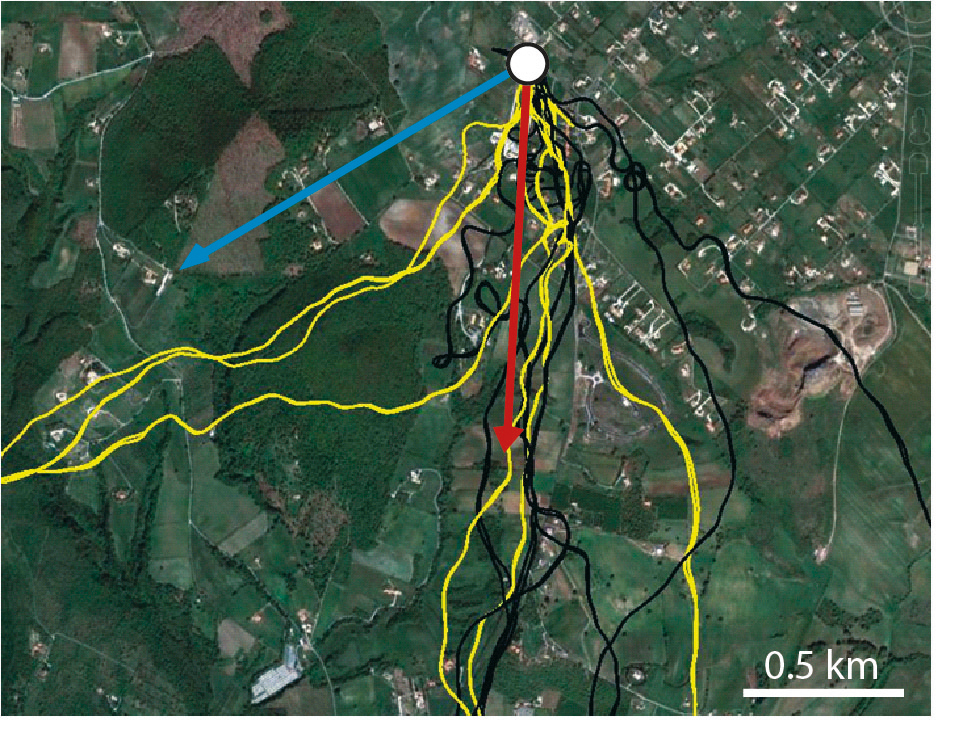

For their experiments, Blaser and her colleagues fitted homing pigeons with miniature GPS loggers in order to monitor the birds’ flight paths. Beforehand the researchers trained the pigeons not to obtain food in the home loft, as was normally the case otherwise. “We fed the pigeons in a second loft around thirty kilometers away, from where they each had to fly back to their home loft,” says Blaser, explaining the structure of the experiment. The scientists then brought the pigeons to a third place unknown to the pigeons in completely unfamiliar territory. This release site was in turn thirty kilometers from the home loft and the food loft. Natural obstacles obscured visual contact between the release site and the two lofts. One group of the pigeons was allowed to eat until satiated before flying home. The other group was kept hungry before starting off. Blaser explained: “With this arrangement, we wanted to find out whether the hungry pigeons fly first to the home loft and from there to the food loft or whether they are able to fly directly to the food loft.”

“As we expected, the satiated pigeons flew directly to the home loft,” explains Prof. Hans-Peter Lipp, neuroanatomist at UZH and Blaser’s supervisor for her doctoral thesis. “They already started on course for their loft and only deviated from that course for a short time to make topography-induced detours.” The hungry pigeons behaved quite differently, setting off on course for the food loft from the very beginning and flying directly to that target. They also flew around topographical obstacles and then immediately adjusted again to their original course. Based on this procedure, Blaser concludes that pigeons can determine their location and their direction of flight relative to the target and can choose between several targets. They thus have a type of cognitive navigational map in their heads and have cognitive capabilities. “Pigeons use their heads to fly,” jokes the young biologist.