The following excerpts are from an article titled “From Disc to Sphere” which was published by Volker M. Welter, a professor in the UCSB Department of the History of Art and Architecture:

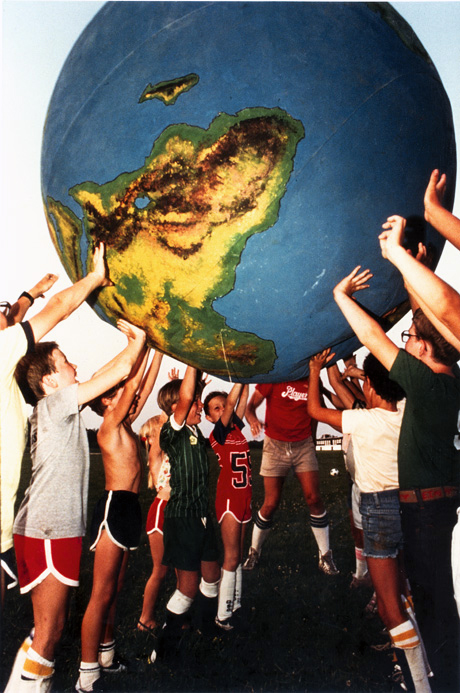

Today, barely an Earth Day celebration takes place during which the participants do not pass an inflatable globe over their heads in order to express a symbolically renewed relationship with the earth. The iconology of this symbol can be traced back both to photographs of Earth taken during NASA’s various missions to outer space, and to our attempts to comprehend our environment with the help of maps and globes.

Chronologically, however, inflatable earth balls preceded such imagery and became the first symbol that 1960s environmentalism adopted in order to act out a new existential relationship with the earth. While playing with an inflatable globe seemingly promoted this emerging sensibility, the motif—man playing with the earth—in fact recalls earlier images from the history of modernity’s relationship to the planet.

Globes are one way of representing the earth. Initially of rather small size, large-scale spheres from the nineteenth century onwards allowed for more direct forms of encounter. Insofar as they too adopt a bird’s eye view, aerial and outer-space photographs can be considered an extension of maps. Yet all three differ in regard to their ontological implications for man’s relationship with Earth. Some postmodern critiques notwithstanding, maps did aim at understanding the spaces they depicted. Maps not only made these previously uncharted terrains available to explorers, adventurers, and armchair travelers, but, crucially, their initial creation often relied on someone physically traversing the spaces that were subsequently represented.

Just over one hundred years passed between the first camera image of a section of the earth, photographed by Nadar from a balloon in 1858, and the extraterrestrial views of segments of our planet taken by the US satellite Explorer VI in August 1959. In between, hot air balloons offered views of Paris, reconnaissance kites allowed for glimpses into enemy trenches during the Great War, and in World War II, airplanes achieved the same.

The instant visual overview that photographs of the earth offer suggests usefulness comparable to that of maps. Yet, in the words of art-historian-turned-geographer Denis Cosgrove, though “intensely geographical,” such images are not, therefore, “cartographic image[s]”—while maps represent in an abstract manner, high altitude, aerial, and extraterrestrial photographs offer a more direct, if unusual, depiction of reality.

The increasing ability of later twentieth-century man to view the earth from ever further away in outer space constitutes another qualitative shift, this time from viewing parts of the planet to seeing the whole. Gazing at the entire globe from outer space no longer means looking down, but back from a distance. The height of the former viewpoint is measurable with regards to a base, usually the surface of the planet; the act of measuring establishes, together with gravity, a clear sense of above and below. The loss of this grounded dimension in gravity-free outer space means that height morphs into mere distance between objects, such as spaceships full of astronauts and planets like the earth. Consequently, outer-space travel initiated, according to philosopher Günther Anders, a process of “spatial distancing from the earth” that gradually revealed our planet as “an ownerless celestial body, the flotsam of the universe,” while accompanying outer-space photographs illustrated man’s “cosmic eccentricity” as an accidental bystander somewhere in space.

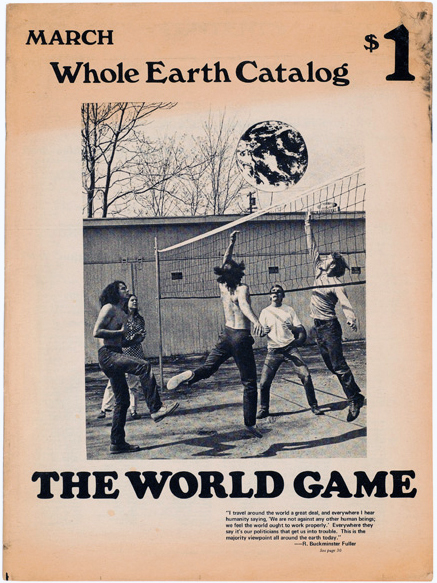

As Stewart Brand began to ponder in early 1966 the ideas that eventually crystallized in the Whole Earth Catalog, he started selling little white buttons that asked: “Why haven’t we seen a photograph of the Whole Earth yet?” Crucial is the adjective whole, as Brand explained in a later essay, for “the earth [is] curved … closed on itself.” This fact, while knowable in the abstract, had not up until then been visible to the inhabitants of the planet; thus, he continued, “people perceived the earth as flat and infinite, and that … was the root of all their misbehavior.” Changing such erroneous perception required the holistic expansion of man’s consciousness, to fully grasp “that it [Earth] was curved, think it, and finally feel it.” Subsequently, Brand conceived “a six-foot diameter canvas and rubber pushball of the type he had played with in Army boot-camp training. This one [was] painted with continents, oceans, and cloud swirls.”16 This first “earth ball” was created in 1966 for the New Games, an initiative that aimed at channeling human aggression into noncompetitive and peaceful tournaments. In short, two years before an image of the entire earth was featured in 1968 on the cover of the Whole Earth Catalog’s inaugural issue, Whole Earth environmentalism had already adopted as its symbol an inflatable globe that mimicked the earth as seen from outer space rather than being a three-dimensional model of a two-dimensional world map.

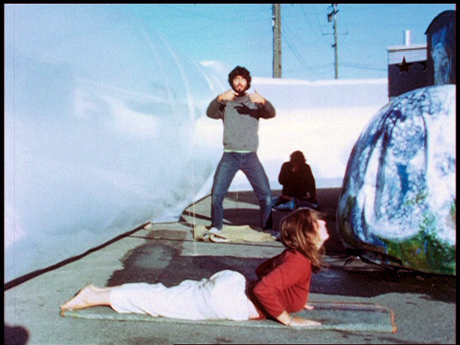

Having thus taken possession of the planet by inflating it, earth balls were thrown around, rolled up and down hills, and had to endure hirsute hippies throwing themselves at and over them as everyone welcomed “the chance to play with the planet, whether … pushing, passing or throwing it; kicking or hugging it; on top, beneath, or against it.” This may have been a joyful and novel interaction, but the ease with which the earth was turned into a toy firmly roots this motif in modernity.

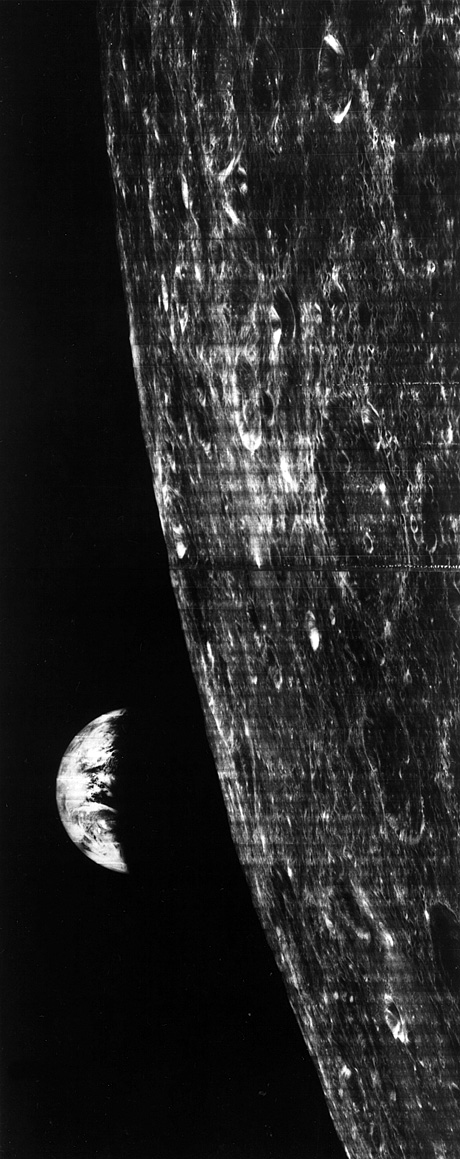

Considering that extraterrestrial travel had catapulted man into spatial dimensions so vast as to be unfathomable, this reaction may astonish. Yet, one response to the expansion of human experience, argues Anders, was to reign in the newly accessible universe by drawing it back into an orbit that was solely defined by the scale of the human mind and body. This focus on human spatiality is why it was not the Lunar Orbiter I photograph of the whole earth published in 1966 but instead a near-identical one, taken two years later from Apollo 8, that acquired fame as the iconic “earthrise” image. This was, first of all, because it was astronauts, and not a satellite, who took the photograph; more importantly, however, the earthrise image was at some point flipped ninety degrees, a move that shifted the moon from its upright position at the right edge of the frame to a horizontal one that grounded man again in relation to a recognizable horizon.

Editor’s note: Many thanks to Professor Dan Montello for suggesting this material.