The following is from the University of Utah’s News Center, posted January 6, 2014 with the title above:

“Last year’s gigantic landslide at a Utah copper mine probably was the biggest nonvolcanic slide in North America’s modern history, and included two rock avalanches that happened 90 minutes apart and surprisingly triggered 16 small earthquakes, University of Utah scientists discovered. The landslide – which moved at an average of almost 70 mph and reached estimated speeds of at least 100 mph – left a deposit so large it “would cover New York’s Central Park with about 20 meters (66 feet) of debris,” the researchers report in the January 2014 cover study in the Geological Society of America magazine GSA Today.

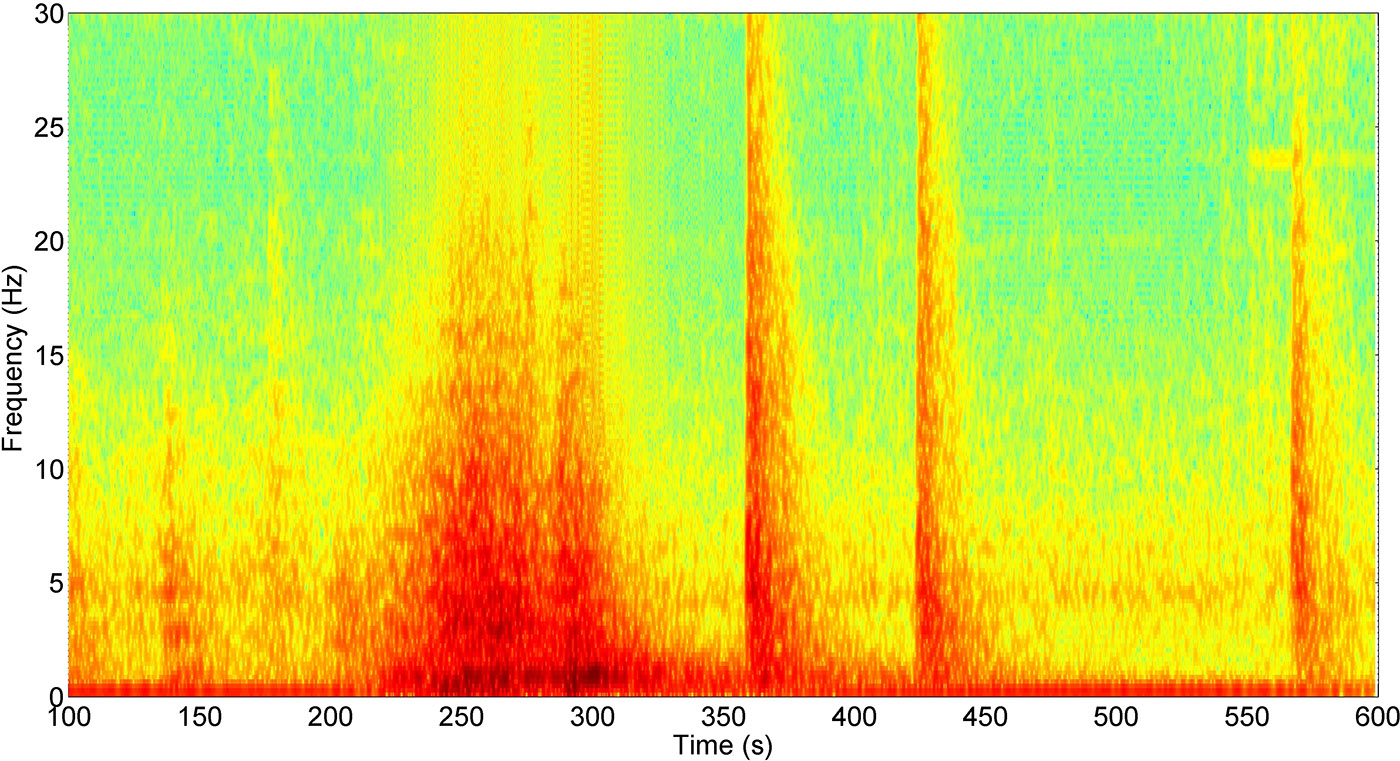

While earthquakes regularly trigger landslides, the gigantic landslide the night of April 10, 2013, is the first known to have triggered quakes. The slide occurred in the form of two huge rock avalanches at 9:30 p.m. and 11:05 p.m. MDT at Rio Tinto-Kennecott Utah Copper’s open-pit Bingham Canyon Mine, 20 miles southwest of downtown Salt Lake City. Each rock avalanche lasted about 90 seconds.

While the slides were not quakes, they were measured by seismic scales as having magnitudes up to 5.1 and 4.9, respectively. The subsequent real quakes were smaller. Kennecott officials closely monitor movements in the 107-year-old mine – which produces 25 percent of the copper used in the United States – and they recognized signs of increasing instability in the months before the slide, closing and removing a visitor center on the south edge of the 2.8-mile-wide, 3,182-foot-deep open pit, which the company claims is the world’s largest manmade excavation.

Landslides – including those at open-pit mines but excluding quake-triggered slides – killed more than 32,000 people during 2004-2011, the researchers say. But no one was hurt or died in the Bingham Canyon slide. The slide damaged or destroyed 14 haul trucks and three shovels and closed the mine’s main access ramp until November. “This is really a geotechnical monitoring success story,” says the new study’s first author, Kris Pankow, associate director of the University of Utah Seismograph Stations and a research associate professor of geology and geophysics. “No one was killed, and yet now we have this rich dataset to learn more about landslides.”

There have been much bigger human-caused landslides on other continents, and much bigger prehistoric slides in North America, including one about five times larger than Bingham Canyon some 8,000 years ago at the mouth of Utah’s Zion Canyon. But the Bingham Canyon Mine slide “is probably the largest nonvolcanic landslide in modern North American history,” said study co-author Jeff Moore, an assistant professor of geology and geophysics at the University of Utah. There have been numerous larger, mostly prehistoric slides – some hundreds of times larger. Even the landslide portion of the 1980 Mount St. Helens eruption was 57 times larger than the Bingham Canyon slide.

News reports initially put the landslide cost at close to $1 billion, but that may end up lower because Kennecott has gotten the mine back in operation faster than expected. Until now, the most expensive U.S. landslide was the 1983 Thistle slide in Utah, which cost an estimated $460 million to $940 million because the town of Thistle was abandoned, train tracks and highways were relocated, and a drainage tunnel built” (read the complete news article here; the GSA Today cover article can be found here).