The following is a June 27, 2013, Newsroom Release from North Carolina State University with the title above:

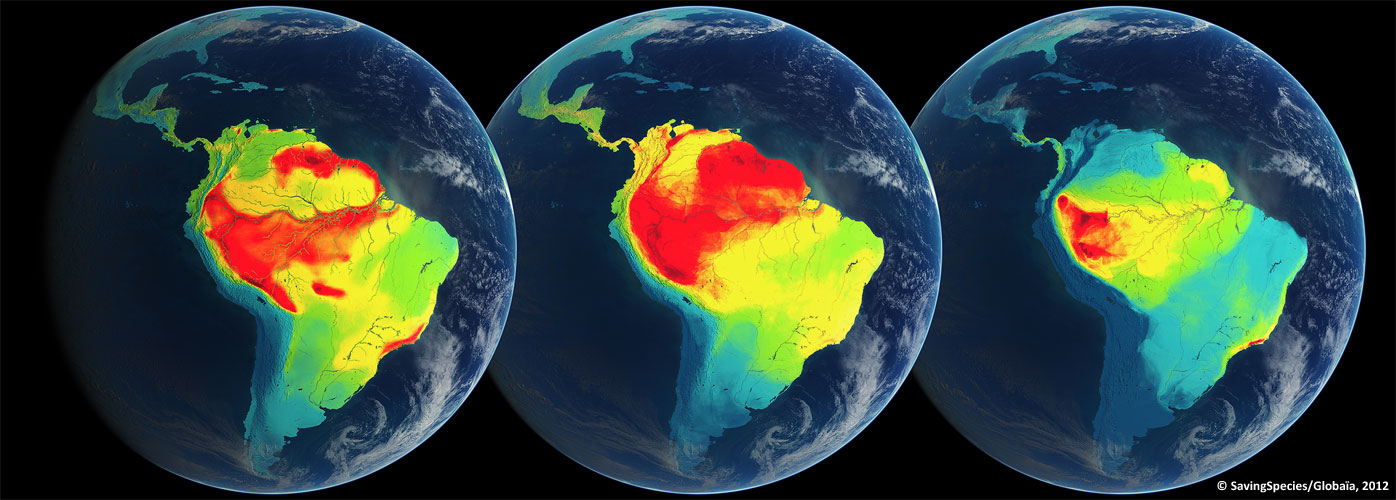

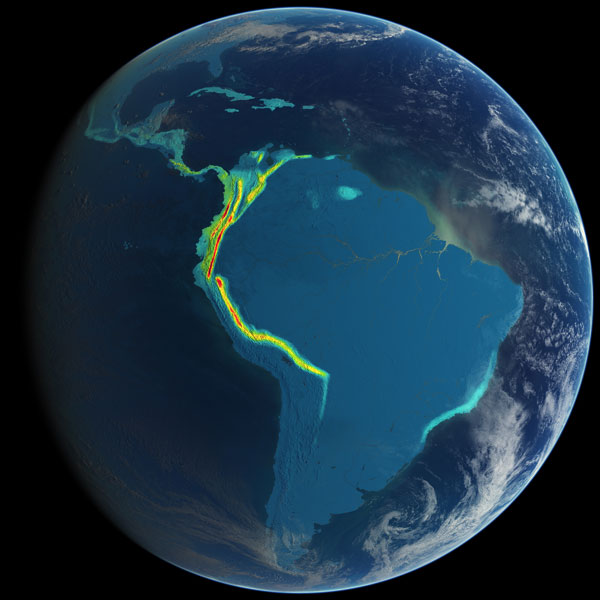

In stunning color, new biodiversity research from North Carolina State University maps out priority areas worldwide that hold the key to protecting vulnerable species and focusing conservation efforts. The research, published online in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, pinpoints the highest global concentrations of mammals, amphibians, and birds on a scale that’s 100 times finer than previous assessments. The findings can be used to make the most of available conservation resources, said Dr. Clinton Jenkins, lead author and research scholar at NC State University.

“We must know where individual species live, which ones are vulnerable, and where human actions threaten them,” Jenkins said. “We have better data than in the past—and better analytical methods. Now we have married them for conservation purposes.”

To assess how well the bright-red priority areas are being protected, researchers calculated the percentage of priority areas that fell within existing protected zones. They produced colorful maps that offer a snapshot of worldwide efforts to protect vertebrate species and preserve biodiversity. More maps are available in high resolution on the Saving Species blog.

“The most important biodiversity areas do have a higher rate of protection than the global average. Unfortunately, it is still insufficient, given how important these areas are,” said co-author Dr. Lucas Joppa with Microsoft Research in Cambridge, England. “There is a growing worry that we are running out of time to expand the global network of protected areas.”

Researchers hope their work can guide expansion of protected areas before it’s too late. “The choice of which areas in the world receive protection will ultimately decide which species survive and which go extinct,” says co-author Dr. Stuart Pimm of Duke University. “We need the best available science to guide these decisions.” Jenkins’ work was supported by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Blue Moon Foundation, and a National Aeronautics and Space Agency Biodiversity Grant.

“Global patterns of terrestrial vertebrate diversity and conservation” was published online, the week of June 24, in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences; authors: Clinton N. Jenkins, North Carolina State University, Stuart L. Pimm, Duke University, and Lucas N. Joppa, Microsoft Research, Cambridge, England.

Abstract:

Identifying priority areas for biodiversity is essential for directing conservation resources. Fundamentally, we must know where individual species live, which ones are vulnerable, where human actions threaten them, and their levels of protection. As conservation knowledge and threats change, we must reevaluate priorities. We mapped priority areas for vertebrates using newly updated data on more than 21,000 species of mammals, amphibians, and birds. For each taxon, we identified centers of richness for all species, small-ranged species, and threatened species listed with the International Union for the Conservation of Nature. Importantly, all the analyses were at a spatial grain of 10 by 10 km, 100 times finer than previous assessments. This fine scale is a significant methodological improvement, because it brings mapping to scales comparable with regional decisions on where to place protected areas. We also mapped recent species discoveries, because they suggest where as-yet-unknown species might be living. To assess the protection of the priority areas, we calculated the percentage of the priority areas within protected areas using the latest data from the World Database of Protected Areas, providing a snapshot of how well the planet’s protected area system encompasses vertebrate biodiversity. Although the priority areas do have more protection than the global average, the level of protection still is insufficient given the importance of these areas for preventing vertebrate extinctions. We also found substantial differences between our identified vertebrate priorities and the leading map of global conservation priorities, the biodiversity hotspots. Our findings suggest a need to reassess the global knowledge of conservation resources to reflect today’s improved knowledge of biodiversity and conservation.