The following is an article for houmatoday.com by Staff Writer Nikki Buskey titled “As coast erodes, names wiped off the map” and posted 5/1/13:

For decades, south Louisiana residents have watched coastal landmarks disappear as erosion worsened and the Gulf of Mexico marched steadily inward. Now federal officials are wiping the names of these vanished places off the map. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Office of Coast Survey began remapping coastlines in south Louisiana in 2011 but have found many of the lakes, bays, bayous and passes that once existed no longer have the defining features to stay on the map. “It shows the sheer travesty of the situation we’re facing in coastal Louisiana,” said Lafourche Parish Administrator Archie Chaisson. “These places, their entire identity, are being wiped off the map.”

The office remapped coastlines in Plaquemines Parish and will remove 31 place names from the map, including Grand Bayou Carrion Crow, Fleur Pond and Yellow Cotton Bay. They will remain in historic archives but will no longer be used in current maps. The remapping process will continue along the coast for the next few years. Meredith Westington, chief geographer with NOAA’s Office of Coast Survey, said she’s never seen this level of change before in her eight years working in the office: “In the course of changing the shoreline, we found a lot of place names that were no longer attached to any features,” she said. In some cases, for example, they found that pieces of land that had once separated lakes or bays had disappeared, leaving them indistinguishable. “It’s pretty substantial,” she said. “This is 31 names, and there are more coming.”

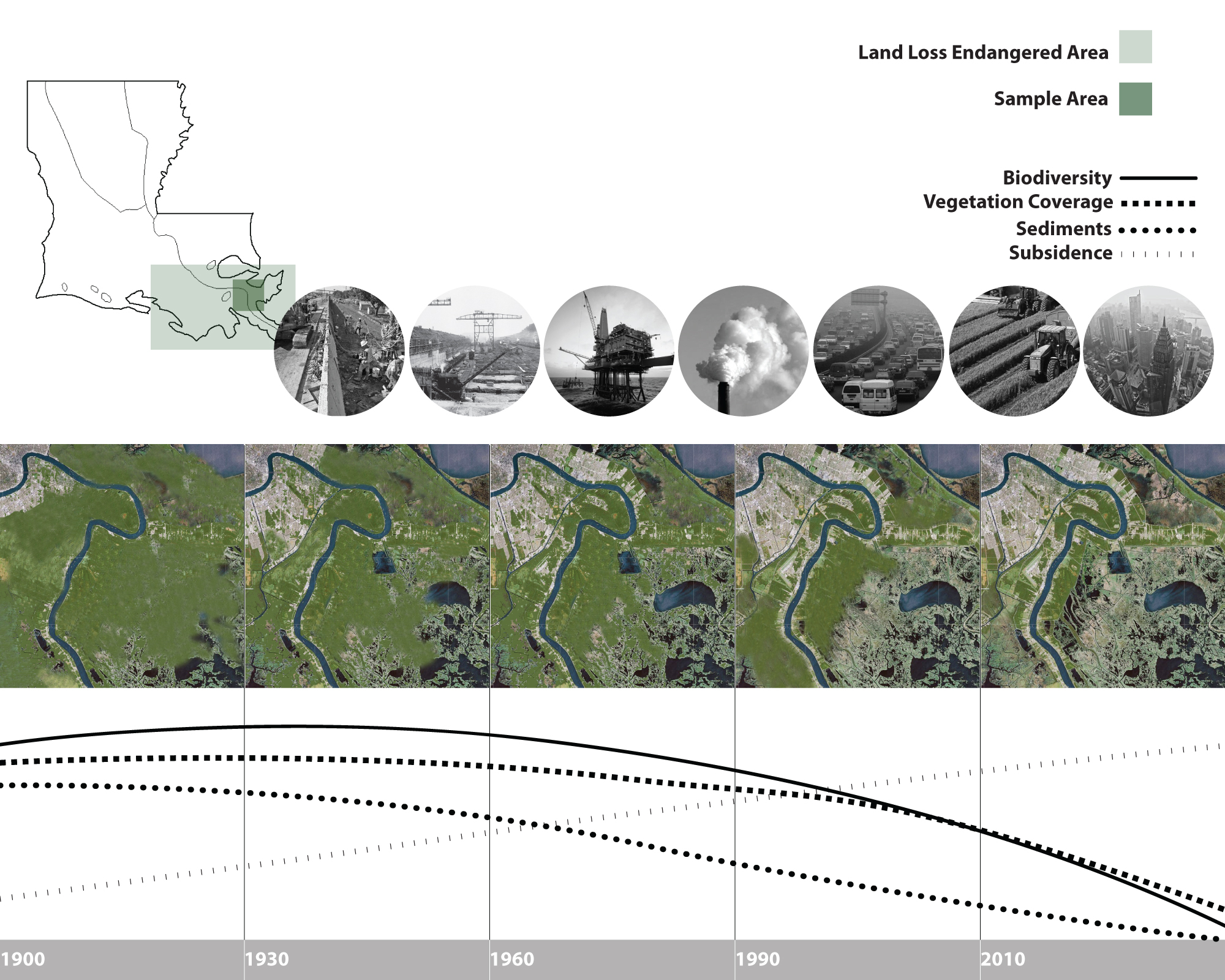

The erosion causing this massive disappearing act is from subsidence, or the sinking of land, and salt water intrusion. When the Mississippi River was leveed in to prevent flooding, it also cut communities such as Terrebonne and Lafourche parishes off from the rich river sediment and fresh water that built and sustained land for decades. Disappearing places aren’t anything new to residents of lower Terrebonne and Lafourche, said Terrebonne Coastal Restoration Director Nic Matherne. But he’s hopeful such a dramatic step could raise awareness of the problem of coastal erosion for residents elsewhere in Louisiana and around the country.

And these areas that are gone now are likely not coming back. The state has drafted a 50-year, $50 billion master plan to address coastal restoration and protection that is aiming for no net loss of wetlands in the next 50 years. If the plan works, Louisiana would see more land gained than lost by 2042. But that goal spans the entire coast, and Terrebonne and Lafourche officials have been concerned about the lack of restoration options available locally in the plan. The state has stressed that hard choices are necessary to save the coast, and there’s not enough time or money to save everyone. (Read the entire article here.)

Editor’s note: Many thanks to John Cloud (PhD 2000) for suggesting this material.