After quite a day’s travel and quite a three day stay in Assam, I’ve just arrived in Delhi for a formal National Geographic dinner tonight. While the 3 a.m. wake up call this morning was excruciating, and the drive from Kaziranga to Guwahati a classic bit of India travel (bumpy, slow, truck heavy, cold, misty, and with a roof vent in the bus stuck open), my day was made by having a clear view during the flight here of the front range of the Himalaya all the way from Bhutan across Nepal. We were flying at 30,000 feet, and although the peaks were far off, they were just about level with the plane.

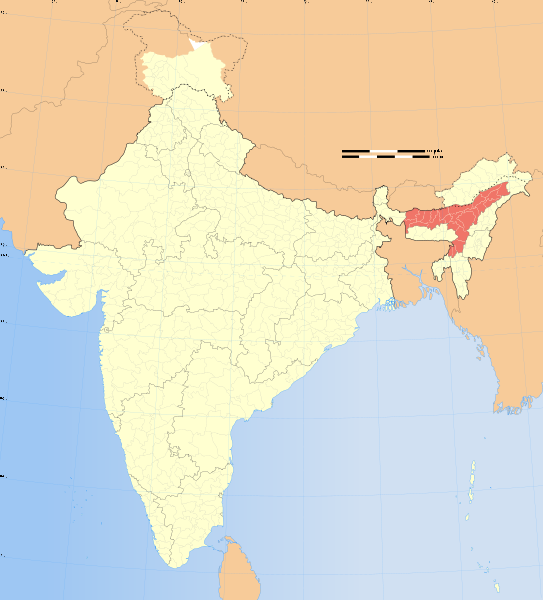

Also a once-in-a-lifetime experience was Kaziranga National Park. We toured both the east and west of the park, a stretch of low lying land from the south bank of the Brahmaputra River to the foothill of the Khazi Mountains, where we stayed in an ecotourism lodge that was surprisingly comfortable. In four trips into the park (which are taken at sunrise and just before sunset, when the animals are active), I saw Hog deer, Swamp deer, a pair of Hornbills, very many elephants and wild buffalo, and, of course, the famous Great One-horned Rhinoceroses. Kaziranga, now a world heritage site, was made a national park in 1905. At that time, there were only a dozen or so rhinos left, but 100 years of conservation has built the population to 1,855. There are 35 mammal species in the park, 15 of them endangered. The National Geographic Committee for Research and Exploration visit to the site is a result of the August 2010 feature article about Kaziranga in National Geographic Magazine. Enforcement against poaching is thorough; there are 600 rangers, dispersed in remote raised platform camps, and they are authorized to shoot to kill, as they did twice last month. The park can be visited only by permit, and with armed guards.

Two highlights stand out. First, a dawn trip through the elephant grass on elephant back. The park animals have no fear of the elephants, and you can get very close to the fauna. Second, and one of the highlights of the whole trip for me, was seeing a Bengal Tiger in the wild. One of the NGS staff spotted it sleeping from the fourth jeep in a four jeep convoy, I took a photo to show how hard a spotting task this was. We quickly got out of our lead jeep to look, but camera shutter clicks woke the tiger, which started to move away from us but parallel to the trail. We got back in the jeep, drove another 100m and waited. Sure enough the tiger emerged, and saw us from a distance of about 10m. A freshly woken and irritated tiger’s roar from 10m away sure gets the adrenaline pumping! Standing in the back of the jeep I was perfectly placed to get a photo of the tiger’s retreat, and that is the last we saw of him. Quite simply amazing.

Two weeks of early mornings is beginning to take its toll, and I’m glad to be back in a city and not to have to deal with the rural side of India. I’m looking forward to Varanasi tomorrow, and we have both sunset and sunrise cruises on the Ganges to witness the famous Hindu cremations first hand. While I’ll be glad to get home, I must say that the advertising campaign “Incredible India” really hits it on the head. This place is full of surprises, friendly people, exciting customs, and historical richness. I’m quite sure I’ll be back some time soon.

Editor’s note: Professor Clarke has been an “expert” member of the National Geographic Committee for Research and Exploration since 2006. CRE grants have supported the work of famous anthropologists, such as Louis and Mary Leakey; the CRE’s first archaeology grant went to Hiram Bingham in 1912 to excavate Machu Picchu; Simon Newcomb received the first CRE grant for astronomy for his lunar eclipse expedition of 1900; CRE biology grantees include such respected names as Jane Goodall and Dian Fossey; most of the CRE’s first grants were for geographical exploration, including Israel C. Russell’s 1890 mapping expedition of the area of Mt. St. Elias, Robert E. Peary’s 1909 expedition to the North Pole, and Roald Amundsen’s 1914-15 explorations of the South Pole; a 1975 CRE-supported project headed by geologist Walter Alvarez resulted in observations that led him and his father—Nobel Prize-winning physicist Luis Alvarez—to a breakthrough theory, The Alvarez Theory of Extinction; among oceanography’s best known CRE grantees is William Beebe, who in 1934 completed a record-breaking descent inside a heavy steel ball called a bathysphere, and, in addition, much of Jacques-Yves Cousteau’s work was CRE sponsored; and the impressive list goes on. For more, see the National Geographic web site.