“I don’t like to call it a disaster, because there has been no loss of human life. I am amazed at the publicity for the loss of a few birds” (Fred L. Hartley, President of Union Oil Company, commenting on the 1969 Santa Barbara oil spill). While Union Oil’s president callously equated the 1969 Santa Barbara oil spill to “the loss of a few birds,” the public reaction to the environmental disaster acquired long-term local and national dimensions:

- A broad environmental grassroots movement was founded, leading to the first Earth Day in November of 1969. )

- Get Oil Out (GOO) collected 100,000 signatures for a petition to ban offshore drilling

- The Environmental Defense Center was founded ) and the first Environmental Studies program was started at UC Santa Barbara ).

- The California Coastal Commission was created from a statewide initiative. (http://www.coastal.ca.gov). This commission today has powerful control over human activities that impact California’s coastal areas.

- The State Land Commission banned offshore drilling for 16 years, until the Reagan Administration took office.

- President Nixon signed the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 ), leading the way to the July 1970 establishment of the Environmental Protection Agency.

- The California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) became law ).

- Federal and state regulations governing oil drilling were strengthened.

- A CIA owned U-2 Spy Plane took the first ever air photo reconnaissance images of Santa Barbara for peaceful purposes other than mapping of denied territory (Marx, 1984).

- Federal Government founded the Civil Applications Committee, aimed at coordinating intelligence and military systems for national emergencies (source).

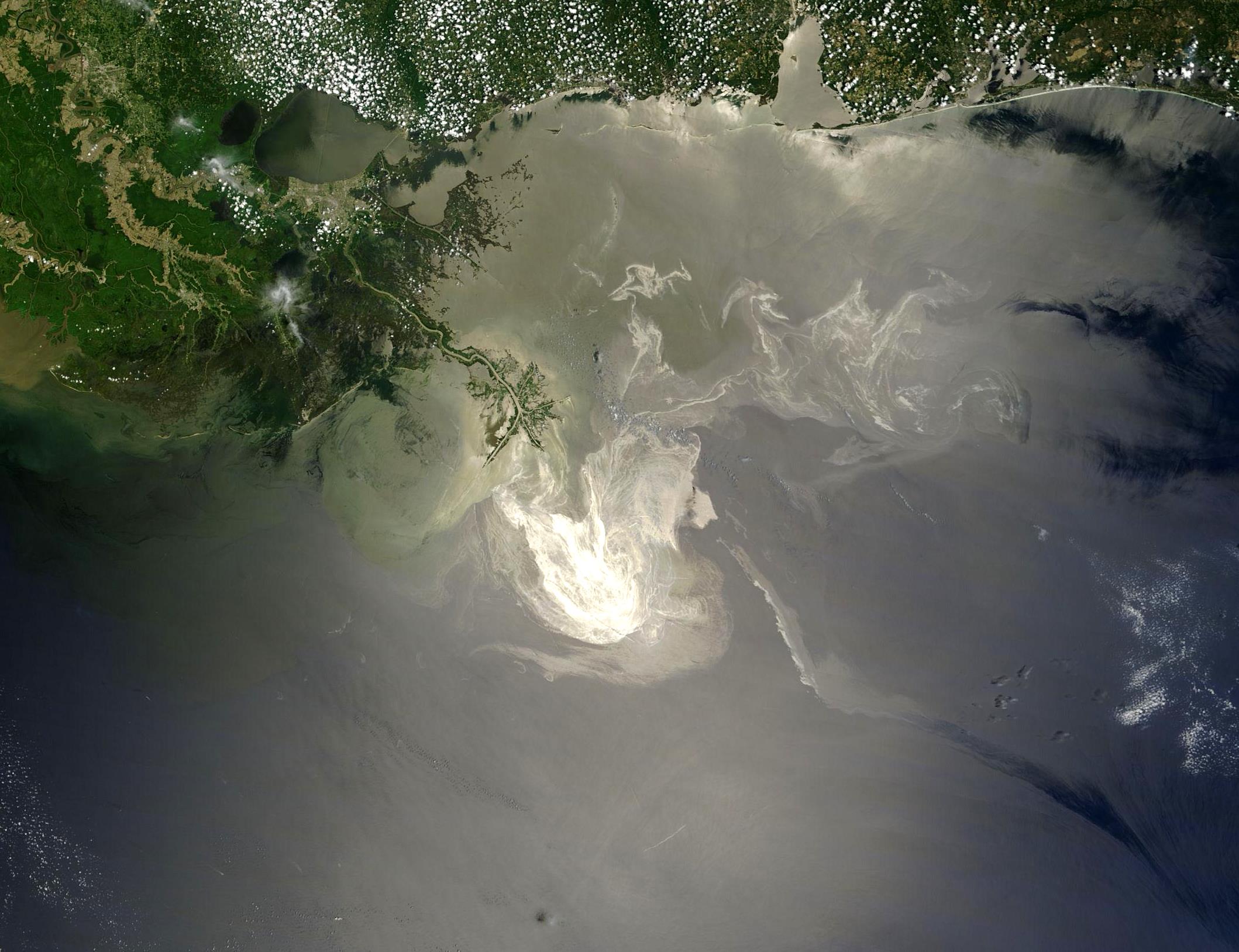

In a BBC article titled “How US and Europe differ on offshore drilling” by Katie Connoly (May 18, 2010), the author notes that “the Gulf of Mexico oil disaster has prompted calls for the US to re-impose a moratorium on offshore oil drilling, which lapsed in 2008 after nearly 30 years. No other country in the world has taken such a tough line on exploitation of offshore oil, so why is the US different?” Ms. Connoly goes on to quote Professor Keith Clarke in order to answer this question: “Drilling in the UK is extremely remote and none of it is clearly visible from the coastline in the way it is in California and Louisiana. In the US, drilling is integrated with local economies so much – and the consequences of disasters are so immediate and apparent – that communities pay more attention than in other parts of the world.”

While the latest oil disaster in the Gulf has muted the “drill, baby, drill” brigade somewhat, “It’s a sad thing from our perspective that it takes a disaster to refocus people’s attention on drilling” (Athan Manuel, The Sierra Club). For Europeans, drilling is out of sight and, therefore, largely out of mind. “But in Santa Barbara, lights from the oil rigs still dot the night sky, a legacy in part attributed to Ronald Reagan’s time as governor of California. With tongues firmly in cheek, locals call them Ronald Reagan’s Christmas Trees” (Connoly, Ibid.). One wonders what Gulf of Mexico locals call their oil rigs…

“The chant is ‘drill, baby, drill.’ That’s what we hear across this country in our rallies because people are hungry for those domestic sources of energy to be tapped into. They know that even in my own energy-producing state we have billions of barrels of oil and hundreds of trillions of cubic feet of clean, green natural gas. Barack Obama and Sen. Biden, you’ve said no to everything in trying to find a domestic solution to the energy crisis. You even called drilling — safe, environmentally-friendly drilling offshore — as raping the outer continental shelf” (Sarah Palin, October 2, 2008 Vice Presidential debate against Joe Biden).