The following article with the title above is by alumnus Kirk Goldsberry who wrote it for fivethirtyeight.com, an award winning website launched by ESPN:

In late October, The Washington Post published a provocative op-ed about the rapidly changing demographics of U.S. cities. An influx of college graduates, it argued, is displacing lower-income African-Americans. Despite rapid overall growth in places such as Austin, Texas, some of America’s “most progressive” cities, according to the Post, are struggling to maintain racial diversity. Here’s a key passage suggesting Austin is Exhibit A: “A recent study we conducted at the University of Texas at Austin reveals that Austin is the only major growth city (a city with over half a million people that saw at least 10 percent growth between 2000 and 2010) that experienced an absolute loss in its African-American population.”

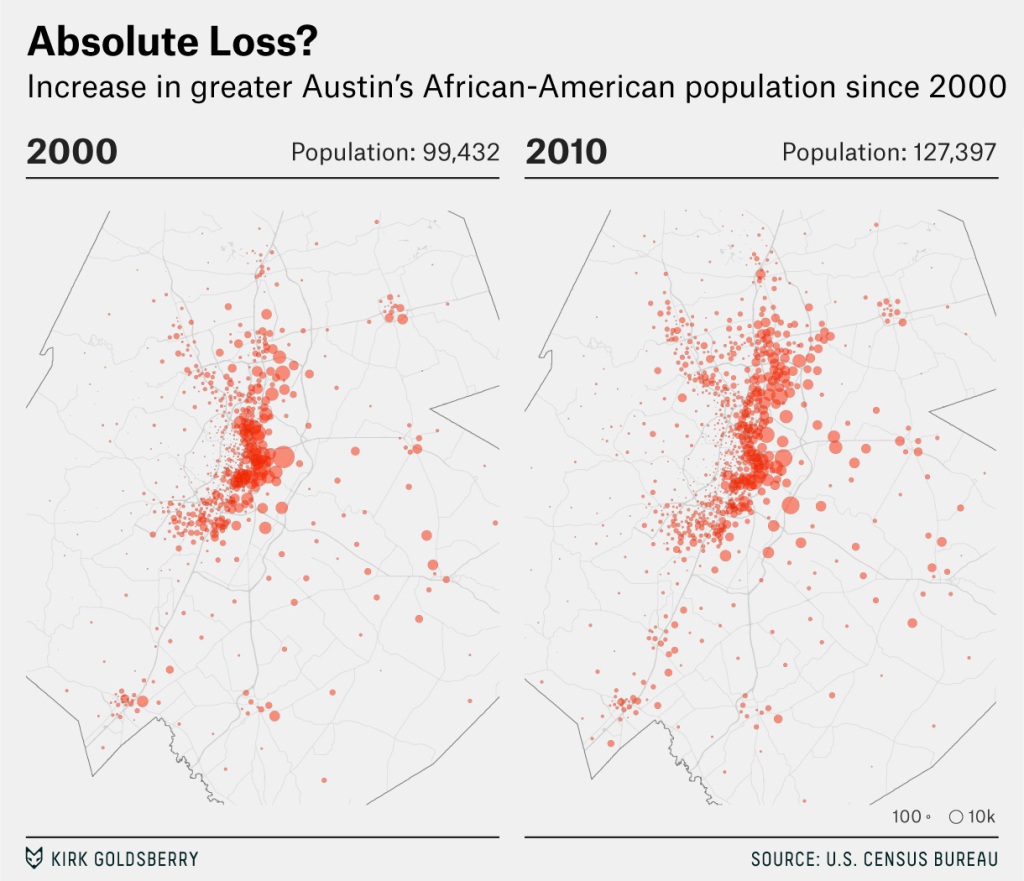

That’s fascinating, and the kind of thing census data should be able to show. Here’s what that “absolute loss” looks like [See Figure 1]. But wait. That can’t be right. These maps leave little doubt that there are more African-Americans in this region than there were 10 years ago. Yet the Post piece is claiming the opposite is true. What’s happening here? How could the Post publish a claim that seems to be flatly incorrect?

Because what we think of as Austin isn’t what it used to be. The place is exploding, and depending on how we define Austin’s city limits, a simple demographic query can have many “correct” answers. Do we include suburbs or surrounding communities? Do we rely solely on the official municipal boundaries? These questions may seem wonky, but their answers often help define our conception of urban space.

Cities grow in two key ways, and when we talk about how “big” a “city” has become, or how fast it has grown, we often conflate two forms of expansion: spatial and demographic. On the one hand, the footprint of a city changes shape; year to year and decade to decade, growing municipalities annex more and more land. On the other hand, urban growth also involves a bigger and bigger batch of humanity living in and around that bulging municipality. But the one hand does not always know what the other is doing, and when population growth outpaces geographic growth — like it has in Austin — things get messy. It becomes foolish to rely on municipal definitions of the city’s boundaries to characterize the overall urban space.

In turn, any analysis or characterization of how a place like Austin is changing is tricky. The findings in the Post present a perfect case. The analysis focuses on the technical municipality, which overlooks hundreds of thousands of residents who self-identify as Austinites. While Austin the municipality may have a clear spatial definition, Austin the “place” is a much murkier thing. [In Figure 2], you see two “official” delineations of Austin. The place called “Austin” is not so simple to define. The city’s definition looks more like a Rorschach plot than it does a city, which is not unusual. But when you plot the city’s population alongside these boundaries, it’s obvious that the official Austin border cuts and weaves through growing settlements.

Unsurprisingly, much of Austin’s population explosion has occurred outside of its famous city limits. Consider the two definitions of Austin in the map [Figure 3] while asking the question the Post did: Were there more or fewer African-Americans in Austin in 2010 than there were in 2000? Simple demographic analyses of population changes in and around “Austin” yield different results, depending on the shape and size of our study area. Through one lens — the one with that wacky Rorschach shape — it looks like there’s a decrease in African-Americans; through another, it looks like there’s a big increase. Although there’s no doubt that Austin’s population has exploded across the board, its black population growth is less clear. This is what geographers call the “modifiable areal unit problem” (MAUP) at its most annoying; two logical delineations of a place produce disparate answers to a simple question.

Still, while that disharmony may be annoying, it also presents important evidence of a curious trend here: A higher share of greater Austin’s black population has recently begun living outside of the city’s formal limits. In 2000, 65 percent of the area’s African-Americans lived within the formal boundary; by 2010, that number was down to 48 percent.

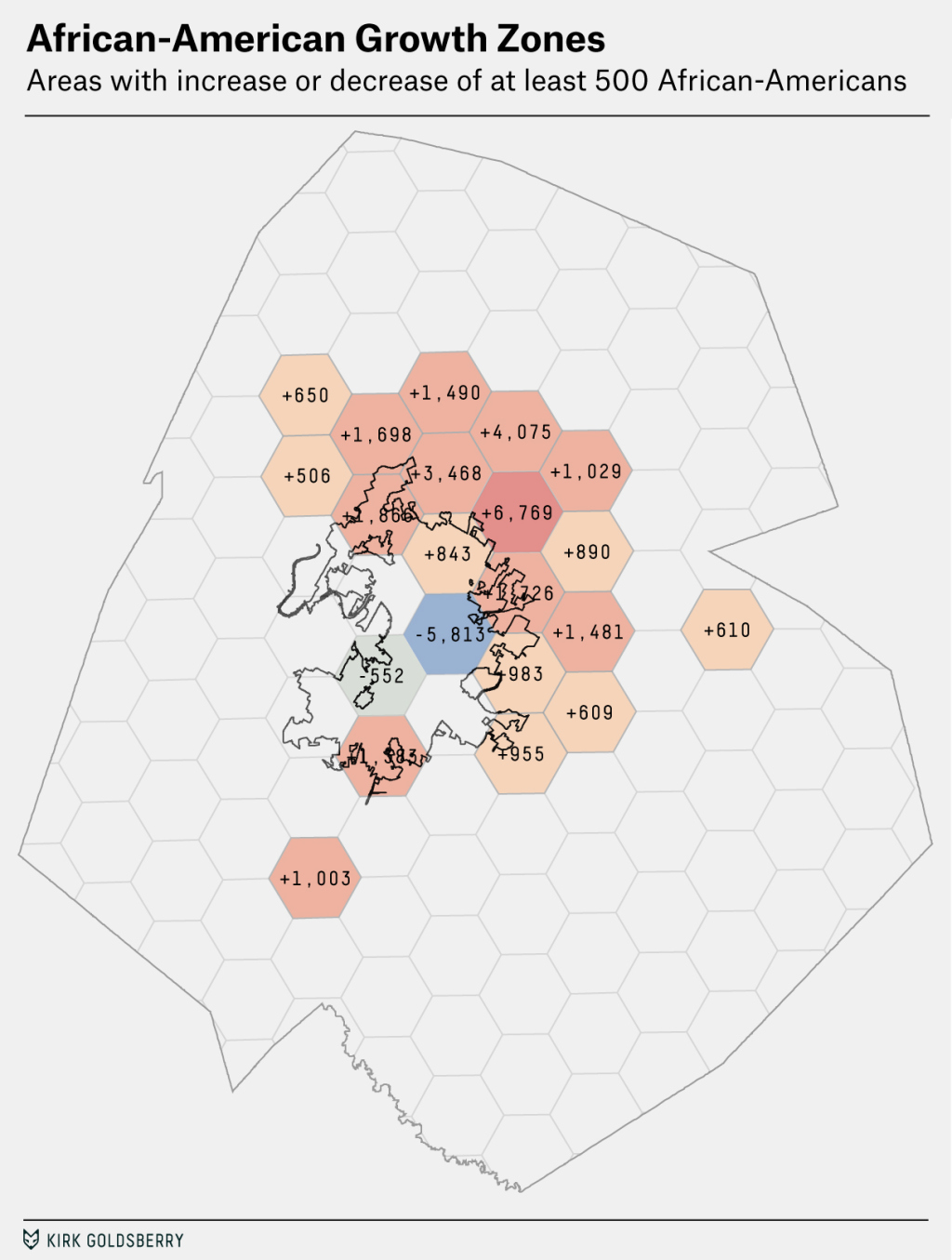

So, it’s incorrect to say greater Austin is experiencing a net loss in its black population, but it’s accurate to suggest some important changes are happening. Those changes have names: gentrification and suburbanization. The map [Figure 4] shows two clear things: 1.) By any definition, there are more black residents in and around Austin than there were in 2000. The five counties that combine to create the census statistical area added 27,965 African-Americans between 2000 and 2010. 2.) There is a curious counter-trend within Austin’s urban core, particularly its historically black East side, which is experiencing a marked decline in its African-American population.

While both the Post piece and the study it’s based on harp on the second point, they neglect to mention the first one. The original study is called “Outlier: The Case of Austin’s Declining African-American Population,” and nowhere in the work do the authors mention that the African-American population has substantially increased in greater Austin. Although they acknowledge they are conducting analyses at the “city” level, it seems strange that they overlook these relevant trends in the metro area.

As Austin, or any city, explodes in size, the city itself changes shape. Its ballooning citizenry begins to bleed into other nearby cities and towns, and at some point the unruly spread of humanity overflows the tidy, arbitrary nature of municipal boundaries. That’s when cities become “metro areas” and when the word “greater” — greater Austin, greater Boston, etc. — starts to creep in front of the city’s name. That’s what led our federal government to concoct “metropolitan statistical areas”; in many cases, they make for better study areas than those antiquated Rorschach town limits.

In Austin, those metropolitan statistical areas are filling up with people of all races. The Post author exploited a common narrative: the new guys (college graduates) pushed the victims (African-Americans) out. But that’s overly simplified: As Austin’s population has exploded in the city, many people of all backgrounds are simply choosing to move to the suburbs [see Figure 5].

It’s undeniable that East Austin has experienced rapid gentrification, but that’s not the only force at work here. Yes, the aimless yearnings of capitalism has brought condominium complexes, craft cocktails, yoga studios and yogurt shops to East Austin. But the suburbs can be appealing, too. An explosion of new suburban housing options and better school districts have enticed black Austinites to move away from the urban core.

Not everyone defecting from East Austin is a victim here. To assume that “college graduates” have “pushed” people away from the urban core is not only incorrect, it’s irresponsible. That’s a lesson that goes for nearly any city — check the narrative before you set your own.