The following article with the above title was written by Dr. Craig McClain, Chief Editor for Deep Sea News, and first posted on June 27, 2012:

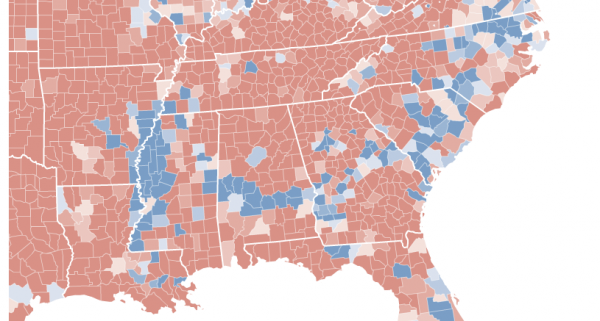

Hale County in west central Alabama and Bamberg County in southern South Carolina are 450 miles apart. Both counties have a population of 16,000, of which around 60% are African American. The median households and per capita incomes are well below their respective state’s median, in Hale nearly $10,000 less. Both were named after confederate officers–Stephen Fowler Hale and Francis Marion Bamberg. And although Hale’s county seat is the self-proclaimed Catfish Capitol, pulling catfish out of the Edisto River in Bamberg County is a favorite past time. These two counties share another unique feature. Amidst a blanket of Republican red, both Hale and Bamberg voted primarily Democratic in the 2000, 2004, and again in the 2008 presidential elections. Indeed, Hale and Bamberg belong to a belt of counties cutting through the deep south–Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, South Carolina, and North Carolina–that have voted over 50% Democratic in recent presidential elections. Why? A 100 million year old coastline.

During the Cretaceous, 139-65 million years ago, shallow seas covered much of the southern United States. These tropical waters were productive–giving rise to tiny marine plankton with carbonate skeletons which overtime accumulated into massive chalk formations. The chalk, both alkaline and porous, led to fertile and well-drained soils in a band, mirroring that ancient coastline and stretching across the now much drier South. This arc of rich and dark soils in Alabama has long been known as the Black Belt. But many, including Booker T. Washington, coopted the term to refer to the entire Southern band. Washington wrote in his 1901 autobiography, Up from Slavery, “The term was first used to designate a part of the country which was distinguished by the color of the soil. The part of the country possessing this thick, dark, and naturally rich soil…”

Over time this rich soil produced an amazingly productive agricultural region, especially for cotton. In 1859 alone a harvest of over 4,000 cotton bales was not uncommon within the belt. And yet, just tens of miles north or south this harvest was rare. Of course this level of cotton production required extensive labor.

As Washington notes further in his autobiography, “The part of the country possessing this thick, dark, and naturally rich soil was, of course, the part of the South where the slaves were most profitable, and consequently they were taken there in the largest numbers. Later and especially since the war, the term seems to be used wholly in a political sense—that is, to designate the counties where the black people outnumber the white.”

The legacy of ancient coastlines, chalk, soil, cotton, and slavery can still be seen today. African Americans make up over 50%, in some cases over 85%, of the population in Black Belt counties. As expected this has and continues to deeply influence the culture of the Black Belt. J. Sullivan Gibson writing in 1941 on the geology of the Black Belt noted, “The long-conceded regional identity of the Black Belts roots no more deeply its physical fundament of rolling prairie soil than in its cultural, social, and economic individuality.” And so this plays out in politics.

This Black Belt with its predominantly African American population consistently votes overwhelmingly for Democratic candidates in presidential elections. The pattern is especially pronounced on maps when a Republican candidate has secured the presidency as Bush did in 2000 and 2004. In Southern states where a Republican secures the nomination, almost the entirety of Black Belt counties still lean Democratic. This leads to a Blue Belt of Democratic counties across the South. Even when Clinton, a Democrat, overwhelmingly took most Southern states, the percentages of those voting Democrat was still highest in the Black Belt counties.

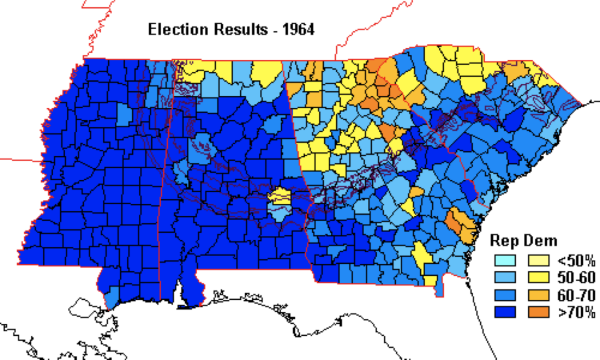

But the Black Belt has not always been visible on maps during elections. The Voting Rights Act, outlawing discriminatory voting practices, was passed in 1965. As result, a year earlier in the 1964 elections larger numbers of African Americans were excluded from the polls in Southern states. And, in turn, the blue band we see today was not visible. Long heralded as the Black Belt for rich dark soils and later for the rich African American culture and population, it may equally be referred to as the Blue Belt to reflect both its oceanic geology and the political leanings that resulted from it.

Editor’s note: Many thanks to Zia Salim, a U.S. Fulbright Fellow – Bahrain 2011-2012 – for suggesting this material and to Dr. Craig McClain, Chief Editor for Deep Sea News, for permission to copy his fascinating article (link).