The following is a Washington Post “Wonkblog” By Emily Badger, posted October 13 with the title above (directed from AAG SmartBrief):

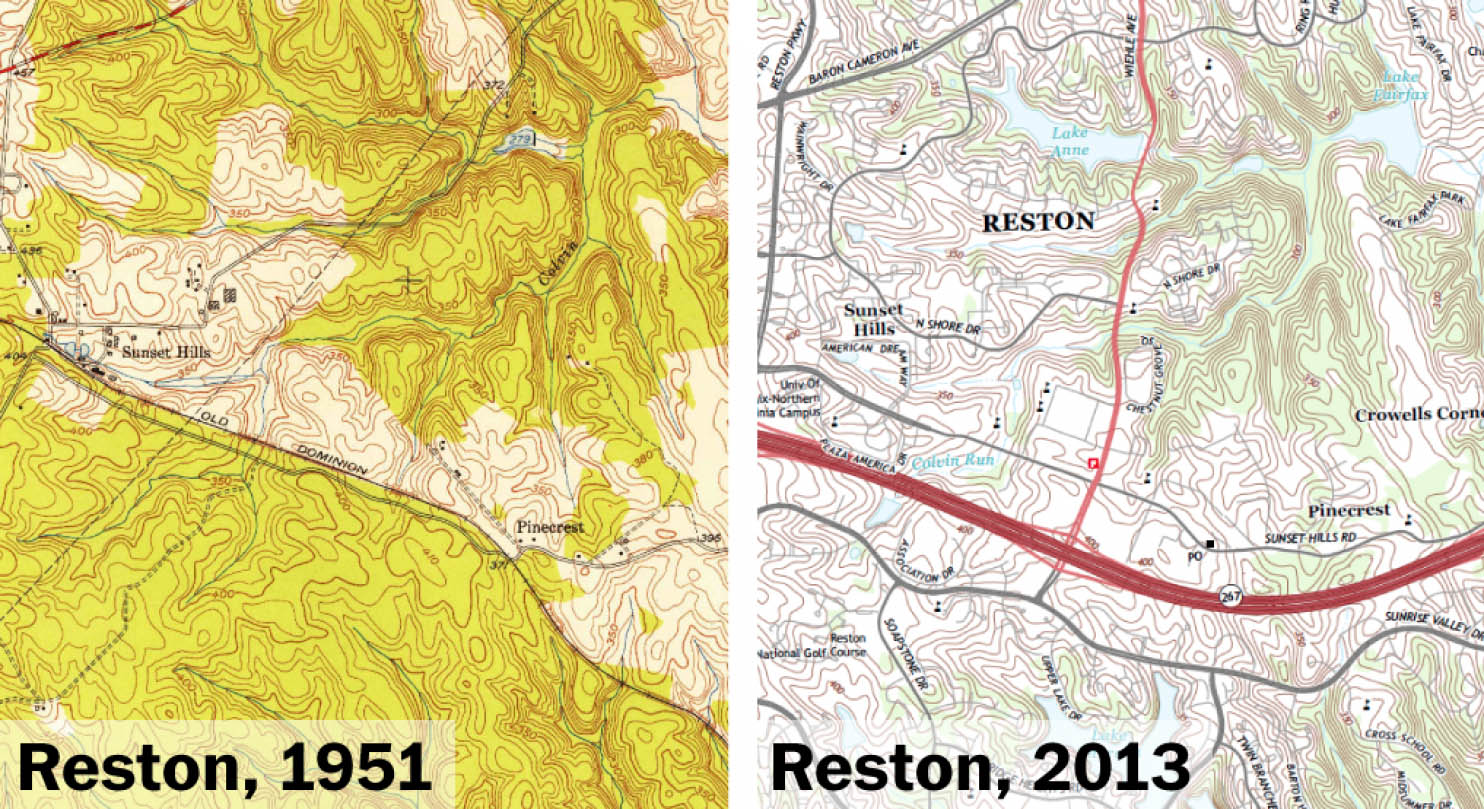

On a 1951 U.S. Geological Survey map of the Virginia land 20 miles west of Washington, Reston doesn’t exist. The place that would come to be Reston is there: the former Old Dominion railroad tracks, the meandering creek called Colvin Run, the faint outlines of a few roads laid long before anyone envisioned a tollway to the airport. But there is no town bearing such a name — Reston — on government maps of the time.

The new developments there have gradually been filled in, added to a vast database of the named places in the United States — landscape features, important locations, newly built suburbs — that ultimately populate official maps of our world. Those maps have been chasing after this quickly evolving place on Washington’s edge for years, as they do anywhere new subdivisions are constructed, or new towns are incorporated, or old places are reinvented with new names. In China, the challenge to cartographers is even more intense: Entire cities now exist where there was nothing a decade ago.

As rapid change and urbanization redraw the world, someone must refresh our maps so that the two-dimensional pictures that give us a common sense of where we live reflect the dynamic, shape-shifting places around us. Quite literally, this is how the U.S. government keeps track of such change: The little-known, 125-year-old U.S. Board on Geographic Names (BGN) maintains a single repository of the definitive name and location of nearly every significant feature worth mapping in the United States (really, you can search through it here), as well as another database of foreign places. And the board is adding names to those very long lists all the time.

In Reston, Lake Audubon, which itself didn’t exist in 1951, was added to the database in 1990. The “Bank of Potomac Shopping Center” and “Plaza America Industrial Park” were noted in 1994. Buzz Aldrin Elementary School was recorded in 1996, Reston Town Center in 2004, the Wiehle-Reston East Metro Station just last year.

The BGN makes sure that “Reston” is never spelled “Restin,” that “Wolf Trap” is always written in two words, that we all agree the reservoir south of the tollway is called “Lake Thoreau.” “Subdivisions and developments are one of the most difficult things to keep track of,” says Lou Yost, the executive secretary for the Domestic Names Committee of the board.

By the end of the last fiscal year, the BGN’s domestic names database included more than 2.7 million names, spanning the country’s towns and schools, airports and islands, streams and more. More than 12,000 were added that year alone, reflecting a national map that hasn’t stopped evolving, even if we long ago believed we’d discovered everything.

The BGN maintains a similar database of all the known and named places outside the U.S, even undersea, their native words often carefully transliterated from other alphabets. That trove contains nearly 10 million names, describing about 6 million features (some with more than one recognized name). In the third quarter of this year, 57,000 new names were added — just in China.

These names, and the coordinates attached to them, turn up in National Park brochures, Forest Service maps, NOAA coastal charts, military maps, State Department documents and the definitive topographic maps, like the one above, covering the entire United States that you can order from the USGS. Private companies rely on the database. So does National Geographic.

“There’s been a shift in the way that we think about maps,” says Bob Davis, chief of the cartographic data services branch within the National Geospatial Program at the USGS. “Even if you went back 15 to 20 years ago, the map product itself – that topo map that came out and was printed on paper – that was the cartographic bible, and every feature was derived from that map.” If you wanted to digitize information 20 years ago on, say, mountains in Yosemite or suburbs of Washington, you’d have to collect the information first from those paper maps. “Now that has switched,” Davis says. “Maps are derived from data, rather than data being derived from maps.”

That makes it easier to keep up with change and to produce official maps en masse. The USGS now creates more than 18,000 new large-scale topo maps every year, each one covering about 55 square miles of the United States. Each map is updated every three years, and new places and changes in the names database are swept up in that update (along with a lot of other data about elevation, water features, roads and administrative boundaries).

The BGN learns about changes, meanwhile, from local governments or news reports or official documents. Yost’s group must research discrepancies in names where they exist. The foreign-names committee is often searching for names in parts of the world that don’t do their own regular mapmaking, like Afghanistan.

“It’s easy to grab names for stuff,” says Marcus Allsup, a geographer at the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency who heads the foreign names group for the BGN. “But it’s not so easy usually to get the official legal name for that feature in that country.” The federal government’s official name-keeper can’t, in short, just Google it. Google, in fact, relied in part on the BGN’s database when it was first building its own maps. The board’s job sounds arcane, but without it, a lot of things would fall apart. Imagine the Army and the Marine Corps talking about the same town with different names in Afghanistan. Or what would happen if no one could agree on what to call Mount Hood. Or how you’d find Reston if no one had ever added it to a map. (The BGN has also, at various points in its history, been responsible for scrubbing racially offensive place-names, and choosing sides between, say, Denali and McKinley.)

“Having an authoritative source for any type of information is terribly important, because we point back to that,” Davis says. “Otherwise, we’d be dealing with lots of complaints and feedback that ‘well this name should have been Davis Hill, or Badger Valley.'” (Great news! There are eight Badger Gulches, five Badger Canyons and one Badger Valley in the U.S.)

The newly added names in the United States don’t entirely come from freshly paved, man-made development. We continue, in fact, to name the land itself — mountains, islands and the like. “There’s still a bunch out there,” Yost says. We may have mapped everything. But we haven’t named it all. The BGN generally won’t sanction new names in congressionally designated wilderness lands in the United States (to name more streams there would be another kind of human intrusion, like name pollution in nature). But that still leaves a lot of unnamed America, between the newly built airports and subdivisions on the fringe of cities. As for exactly how much of our world we’ve named, Yost pauses, stumped. “I wouldn’t know how to quantify that.”