Some say the world will end in fire, / Some say in ice. / From what I’ve tasted of desire / I hold with those who favor fire. / But if it had to perish twice, / I think I know enough of hate / To say that for destruction ice / Is also great / And would suffice. (“Fire and Ice” by Robert Frost, 1920)

Our planet has been through five mass extinctions, and some scientists think we are undergoing a sixth. The Cretaceous-Tertiary or K-T event was the most recent mass extinction event; it occurred 66 million years ago, and the dinosaurs were among the 76 percent of all species on Earth that went extinct at that time. However, 185 million years before that, there was a mass extinction so devastating that paleontologists have nicknamed it the Great Dying. At that time, 96 percent of all species on the planet were wiped out over a span of roughly 100,000 years. All life on Earth today is descended from the 4% of species that survived.

“The fact that the vast majority of the species that have existed on Earth have become extinct has led to the suggestion that all species have a finite lifespan, and, thus, human extinction would be inevitable. Dave Raup and Jack Sepkoski found, for example, a twenty-six-million-year periodicity in elevated extinction rates, caused by factors unknown (See David M. Raup. “Extinction: Bad Genes or Bad Luck,” 1992, Norton). Based upon evidence of past extinction rates, Raup and others have suggested that the average longevity of an invertebrate species is between 4-6 million years, while that of vertebrates seems to be 2-4 million years.

The shorter period of survival for mammals lies in their position further up the food chain than many invertebrates, and, therefore, an increased liability to suffer the effects of environmental change. A counter-argument to this is that humans are unique in their adaptive and technological capabilities, so it is not possible to draw reliable inferences about the probability of human extinction based on the past extinctions of other species. Certainly, the evidence collected by Raup and others suggested that generalist, geographically dispersed species, like humans, generally have a lower rate of extinction than those species that require a particular habitat. In addition, the human species is probably the only species with a conscious prior knowledge of their own demise, and therefore would be likely to take steps to avoid it” (source).

Recently, Louise Leakey, grand-daughter of the famous anthropologist Louis Leakey, heated up the debate about the possible extinction of the human race in the relatively near future: “To put the history of life on planet earth into a time perspective, imagine unrolling a toilet roll down a hillside. If there are 400 sheets of tissue paper in the roll, then the very first life in the oceans is seen at sheet 240. The age of the dinosaurs begins at sheet 19. Dinosaurs in their many forms and great diversity are around for 14 and a half sheets. Dinosaurs are extinct by the end of the Cretaceous, 5 squares from the end, making way for the mammals. Our story and place on the timeline as upright walking apes begins only in the last half of the very last sheet. The human story as Homo sapiens, is represented by less than 2 millimeters of this, some 200,000 years.

Our own individual lifetimes cannot be depicted on this final sheet of the toilet roll as it would be too thin a line, yet we have been witness to more change to the planet, to the diversity of life, global climate and natural habitats in this same time period. We are undoubtedly the cause of the sixth mass extinction event that the planet has seen in its history.

The last 50 years has shown an enormous increase in human population, but also extraordinary leaps in technological innovation. The question that needs to be asked is if we can rise to the opportunity, to use our technology to better understand our impact, to stem the tide of extinction on land and in the oceans, to preserve what we have left, and to discover and understand more about our past. What the fossil record does do is to force us to contemplate our place on the planet. We are but one species of several hominids that inhabited planet earth, and like our distant cousins who went extinct fairly recently, our time on planet earth is also finite. It won’t take much to tip the balance against us.”

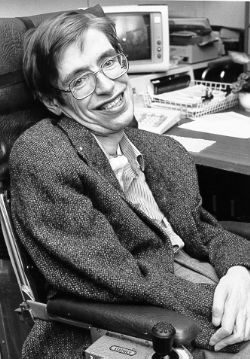

In 2010, Stephen Hawking commented that “Life on Earth is at the ever-increasing risk of being wiped out by a disaster, such as sudden global nuclear war, a genetically engineered virus, or other dangers we have not yet thought of,” and he conjectured that mankind’s only chance of long-term survival lies in colonizing space, as humans drain Earth of resources and face a terrifying array of new threats. “The human race shouldn’t have all its eggs in one basket, or on one planet,” the renowned astrophysicist told the website Big Think. “Our only chance of long-term survival is not to remain inward looking on planet Earth, but to spread out into space,” he added. He warned that the human race was likely to face an increased number of events that threaten its very existence, as the Cuban missile crisis did in 1962. “We are entering an increasingly dangerous period of our history,” said Hawking. “Our population and our use of the finite resources of planet Earth are growing exponentially, along with our technical ability to change the environment for good or ill” (source).

Article by Bill Norrington