In a recent National Public Radio history article with the title above, Richard Gonzales comments: “While Pope Francis is in Washington this week, he is scheduled to canonize Junipero Serra — an 18th century Spanish missionary and the founder of California’s storied network of missions. The canonization of Serra prompts a robust debate: Was the Franciscan friar, as the pontiff proclaims, a saint? Or was he, as many Native Americans argue, a villainous tool of Spanish conquest and genocide? What’s not being talked about is how Serra’s missions became the blueprint for modern California.”

According to historians, “the friars came as part of the colonial expedition, and Spain’s strategy was that by bringing the native peoples into its settlements and way of life, it would cement its hold on the California territory. However, the objective of Serra and the Franciscan missionaries was evangelization” (source). “Serra spent the final half of his life, from the moment he arrived in Mexico City on Jan. 1, 1750, until his death at Carmel on Aug. 28, 1784, struggling to live out his own beliefs in the midst of that complex and bloody reality,” Senkewicz and Beebe write in their 2015 biography. “The manner in which he did so was controversial in his own day and remains no less controversial today.”

“It is estimated that during the Spanish conquest of the Americas, up to eight million indigenous people died, mainly through disease. With the initial conquest of the Americas completed, the Spanish implemented the encomienda system. In theory, encomienda placed groups of indigenous peoples under Spanish oversight to foster cultural assimilation and conversion to Christianity, but in practice it led to the legally sanctioned exploitation of natural resources and forced labor under brutal conditions with a high death rate. Though the Spaniards did not set out to exterminate the indigenous peoples, believing their numbers to be inexhaustible, their actions led to the annihilation of entire tribes such as the Arawak. In the 1760s, an expedition dispatched to fortify California, led by Gaspar de Portolà and Junípero Serra, was marked by slavery, forced conversions, and genocide through the introduction of disease” (Wikipedia: Genocide of indigenous peoples).

The worst abuses of the California Indians, however, came much later, according to Ruben Mendoza of California State University, Monterey Bay (Contested Visions: Fray Junípero Serra, Native Californians, and the Legacy of the Franciscan Missions), who believes the antagonism toward Serra is based on the fact that many of Serra’s critics confuse the impact of Spanish colonizing and missionary activity on the native communities with the decimation of the native peoples after California became a U.S. territory in 1848. The California legislature over time appropriated more than $1 million to pay for bounties for killing California Indians and paid $5 a scalp, said Mendoza, citing “Murder State: California’s Native American Genocide 1846-1873,” by Brendan C. Lindsay (source).

But back to NPR’s discussion of Serra’s missions as a blueprint for modern California. “The government of Mexico secularized the missions in the 1830s after the passage of the Mexican secularization act of 1833. This divided the vast mission land holdings into land grants which became many of the Ranchos of California. In the end, the missions had mixed results in their objectives: to convert, educate, and ‘civilize’ the indigenous population and transform the natives into Spanish colonial citizens. Today, the surviving mission buildings are the state’s oldest structures and the most-visited historic monuments” (source).

“Fast forward through California’s dizzying political development: Mexico loses the territory to the United States in 1848; the gold rush occurs around the same time; California is admitted to the Union in 1850. By the end of the Civil War, the missions were all but abandoned relics of a past that few gold-hungry Americans had time for. But the decrepit and decaying missions would prove to play another pivotal role in California’s explosive growth” (NPR, op. cit.)

“By the 1880s, American real estate developers and railroad barons were looking for ways to attract tourists and new residents to the Golden State, especially Southern California. Spurred on by a cultural movement known as the Spanish Revival, they attached themselves to, and promoted the romantic idea of, an idyllic and comfortable California where people could enjoy the Spanish, or Mediterranean, life style. Rail lines were advertised with promises of taking travelers along ‘the Path of the Padres’” (Ibid.).

“One of the main boosters of this mythology, built on nostalgia for an imagined Spanish past, was Los Angeles Times city editor Charles Fletcher Lummis. As president of the Landmarks Club of Southern California, Lummis pushed for the preservation of the crumbling missions, which he argued were ‘worth more than our money…than our oil, our oranges, or even our climate.’ And so, Senkewicz says, ‘these people create a fantasy past of the missions. You get the heroic evangelizing missionaries, and happy contented Indians, and everybody was living together in this bucolic Arcadia’” (Ibid.).

“Ironically, the promotion of the Mission Myth coincided with the declining Hispanic economic and political power in California, writes historian David Weber in “The Spanish Frontier in North America.” ‘Properly laundered and packaged, California’s picturesque Spanish heritage attracted tourists and gave its infant cities a patina of permanence and tradition'” (Ibid.).

“The advent of the automobile in the early 1900s gave new life to the Mission Myth. New car clubs created caravans along the supposed ‘El Camino Real,’ or King’s Highway, that linked the missions. But there was never only one road that linked the missions, according to historian James Sandos, author of “Converting California: Indians and Franciscans in the Missions.” ‘It’s the desire to be associated with the missions that’s so important,’ he says. ‘Myth is ever more comfortable than reality’” (Ibid.).

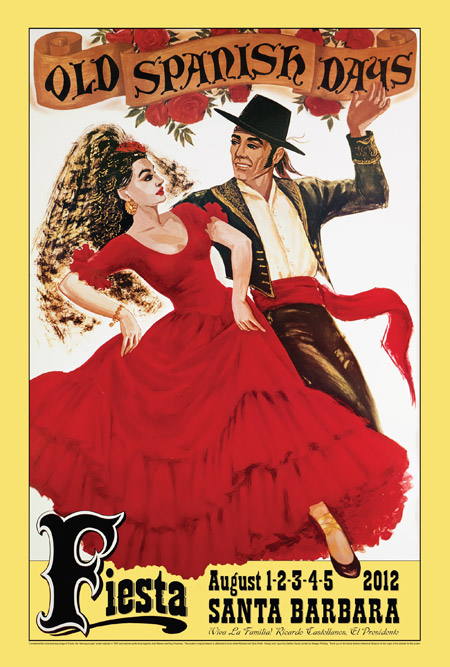

2012_poster_lg.jpg<|>450<|>Santa Barbara’s annual Fiesta was originally called “Old Spanish Days” and is celebrated every year in August. Fiesta started as a tourist attraction, like the Rose Bowl, designed to draw business into the town in the 1920s. “Being that the most important Fiestas in the Spanish and Mexican tradition have always been closely connected with church celebrations, it is only fitting that Santa Barbara’s annual Fiesta has included traditions with the historic Old Mission Santa Barbara. With the gracious involvement of the Franciscan Fathers, those traditions continue today. The 1926 Fiesta held its sunset service at the Mission. A year later, restoration of the Mission from the damage it received in the massive earthquake of 1925 was completed, leading to a celebration on Wednesday evening as a prelude to the opening of Fiesta. There was an Ecclesiastical Procession along the Mission corridor up to the steps of the Mission and followed by a program including addresses by dignitaries, music, and dancing and ending with a reception. From 1927 to the present the tradition has not changed” (source: http://www.oldspanishdays-fiesta.org/history/history_of_fiesta)