UCSB Geography Professor David López-Carr and graduate student Jessica Marter-Kenyon have just had an article published in Nature (Nature, 517, 265–267 [15 January 2015]; doi:10.1038/517265a), titled “Human adaption: Manage climate-induced resettlement.” The authors argue that governments need research and guidelines to help them to move towns and villages threatened by global warming. Excerpts:

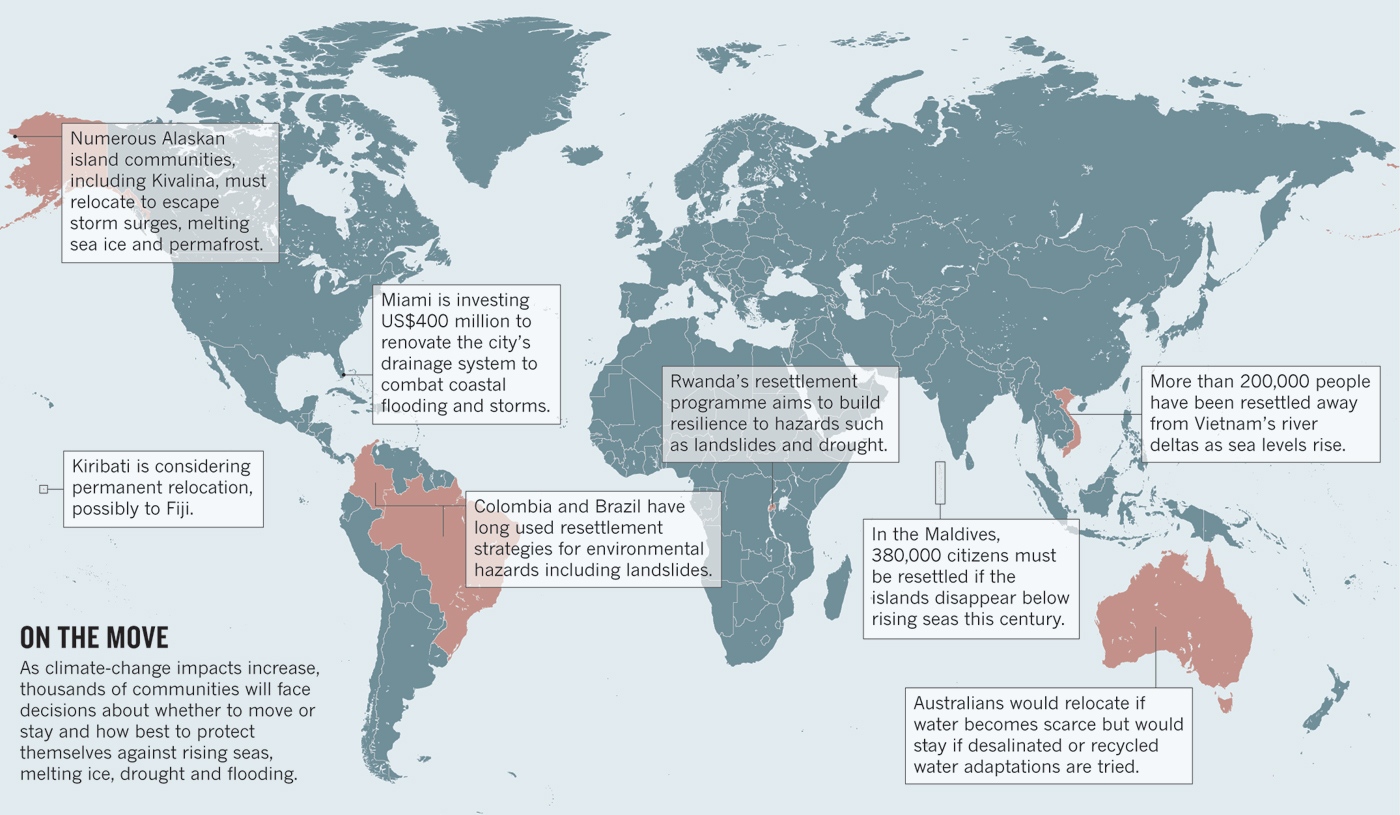

Inupiaq people are watching in horror as climate change claims their homes. Having endured repeated flooding and erosion from sea-ice melting and permafrost thaw, the 400 residents of Kivalina, an Alaskan village on a low barrier island in the Chukchi Sea, voted in 1998 and in 2000 to relocate — together — to coastal sites on higher ground. More than a decade and a half later, Kivalina remains in limbo, its move stymied by institutional, financial, and physical barriers.

No US federal or state agency has a mandate to undertake such mass resettlement, even though the government spent more than US$15 million on erosion control between 2006 and 2009. Kivalina has failed to raise funds through climate lawsuits against oil and gas companies. And it has yet to identify suitable relocation sites. Meanwhile, the village’s water-supply and waste-storage systems have been damaged, and it could become uninhabitable within a decade. Tens of thousands of people in more than 85% of Alaska’s 213 native villages face similar threats.

Papua New Guinea, China, and Vietnam have already relocated communities that were vulnerable to flooding. More than a dozen developing countries, including Uganda and Bhutan, have submitted national adaptation plans to the United Nations that involve population resettlement. Sea-level rise this century threatens the cultural and national survival of several low-lying island nations in the Pacific and Indian oceans. By 2050, climate-related hazards such as flooding, soil salinization, coastal erosion and droughts could displace hundreds of millions of people around the world from their homes, either temporarily or permanently.

In many cases, the best way to protect cultures, livelihoods and social links will be to move as a group. Yet population relocation is practically off the climate-policy radar. The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) did not officially recognize the need for such resettlement until 2010. And science has barely begun to examine the human and environmental drivers, costs and consequences. How severe must a threat — real or perceived — be for people to feel compelled to move? What determines whether they relocate as individuals or together? And how can the social, economic, and psychological downsides of population resettlement be minimized?

Social and environmental scientists and policy-makers need to invest in research to better understand and manage such resettlement. Relocation must be incorporated into climate-adaptation policy discussions and funding initiatives in the run-up to the next UNFCCC Conference of the Parties (COP) in Paris in December.

Institutional and legal systems remain ill prepared for managing relocation in response to climate threats. For example, the US Federal Emergency Management Agency, which provides federal aid for preparing for disasters and for relief and recovery after them, has little power to manage pre-emptive resettlement. It can support community relocation only once disaster strikes, and only in response to a handful of hazards — including drought and hurricanes, but not the severe erosion that threatens Arctic settlements.

Several international policy initiatives have formed recently to develop resettlement guidelines. For example, the Nansen Initiative led by the Norwegian and Swiss governments is planning a global meeting this year to agree to a set of best practices for dealing with cross-border climate displacement. The Peninsula Principles on Climate Displacement within States, developed in 2013 by a group of scientific and legal experts, provides a similar framework for assisting affected people within national borders.

These efforts are a start, but they remain scant and underfunded and are years from application.