Last week’s hot spell, culminating in record-breaking temperatures in Santa Barbara County, has drawn comparisons with Goleta’s “Great Simoon” of 1859 when, supposedly, the temperature hit 133°F (56.1°C), a record in the United States for decades until the U.S. Weather Bureau recorded a temperature of 134°F (56.6°C) in Death Valley, California in 1913. A “simoon” is a strong, superheated and dust-laden wind that occurs in parts of the Middle East (alternative spellings include samiel, sameyel, samoon, samun, simoun, and simoom), and its name derives from the Arabic verb ‘to poison,’ presumably because exposure to such temperatures could cause heat stroke.

According to the Goleta Scrapbook: “Famous for its temperate climate, the Goleta Valley was nonetheless the site of North America’s only simoon, a scorching hot wind that took the temperature to 133 degrees in the middle of the 19th century. The morning of June 17, 1859, dawned sunny and pleasant, with the temperature reaching about 80 degrees by noon. Then, about 1 p.m., according to Walker Tompkins in his book, Goleta the Good Land, a ‘blast of superheated air’ came from the direction of Santa Ynez Peak and hit the Goleta Valley, alarming the residents and sending them scurrying for cover inside thick-walled buildings. By 2 p.m. the temperature had reached an incredible 133 degrees, with the northwest wind bringing ‘great clouds of impalpable dust,’ Tompkins wrote. People reportedly took refuge behind the 3-foot-thick walls of the Daniel Hill adobe, the casa grande at Dos Pueblos Ranch, and the adobe winery at San Jose Vineyard among other places. Rabbits, cattle, snakes (sic) and deer died on their feet according to a government report, and fruit fell from trees to the ground, scorched on the windward side. Birds fell dead from the sky and others flew into wells in search of cooler air and drowned. About 5 p.m. the unimaginably searing, hot wind died down, the report said, the thermometer ‘cooled off” to 122 degrees. Finally, by 7 p.m. the air had dropped to 77 degrees. The Goleta Valley held the continental record for heat for decades until 1913 when Death Valley recorded a temperature of 134 degrees.” According to Tompkins, this temperature, as luck would have it, was recorded by an official US coastal survey vessel that was operating in the waters just offshore, in the Santa Barbara Channel. He also claims that a fisherman in a rowboat made it to the Goleta Sandspit with his face and arms blistered as if he had been exposed to a blast furnace (source).

If you google the subject, you’ll find that most web sites refer to and/or quote Tompkins’ book, “Goleta the Good Land” as the sole source for this historic event (Tompkins, Walker A. [1966]. Goleta – The Good Land. Goleta Am-Vets Post No. 55, 1966; Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 66-23873. P. 57-58). So, who was Walker Tompkins? According to a web site about him, Tompkins “sold his first western novel to Street and Smith, New York. In 1931, in addition to a steady production of wild west fiction, he was writing feature articles for the Sunday Portland Oregonian. Early in his career, Tompkins was dubbed “Two-Gun” for his prodigious output of pulp…Tompkins was a reporter and staff writer for the Santa Barbara News-Press from 1957 to 1973. He wrote the popular Santa Barbara Yesterdays column for the paper and a book of the same name. His daily radio vignettes, also titled Santa Barbara Yesterdays, aired for 20 years on a local station.”

Emails to the California Historical Society and NOAA requesting verification of Tompkins’ version of “the great simoon” went unanswered. It seems unlikely that the (supposed) second highest temperature ever recorded in US history, and one that held the record for decades, isn’t documented outside of Tompkins’ text (but see Editor’s note below). What happened to the log of the US coastal survey vessel that supposedly recorded the historic event, and, if a local fisherman was badly blistered by the heat, what happened to the coastal survey ship’s crew? When asked, Professor Joel Michaelsen commented: “I have never found any outside source to validate Tompkins’ story, and I am highly skeptical of its veracity. I don’t doubt that strong hot, dry downslope winds could kick up lots of dust and produce very high temperatures – but in the 110 F – 115 F range at most. The 133 F just isn’t physically reasonable, as it would require the creation of an extremely hot air mass somewhere to the northeast. Last Monday’s weather was a very good strong example of the sort of conditions that would produce such a heat wave, and our temperatures topped out at least 20 degrees below Tompkins’ figure. Stronger winds could have increased the heating a bit, but not nearly that much. Add to all that meteorologically-based skepticism Tompkins’ well-known tendency to mix liberal doses of fiction into his ‘histories,’ and I think you have a strong case for discounting this one.”

According to USA Today, the USA’s highest temperature (also the official highest temperature in the Western Hemisphere) was 134° on July 10, 1913 in Death Valley, California, and the world’s highest official temperature is 136°, recorded at El Azizia, Libya, on Sept. 13, 1922. However, “Not everyone agrees that the Death Valley and El Azizia records are valid. Some meteorologists say that a sandstorm was going on at the time 134° was measured at Greenland Ranch in Death Valley and that very hot sand and dust could have hit the thermometer inside its shelter, pushing its measurement higher than the actual temperature of the air.”

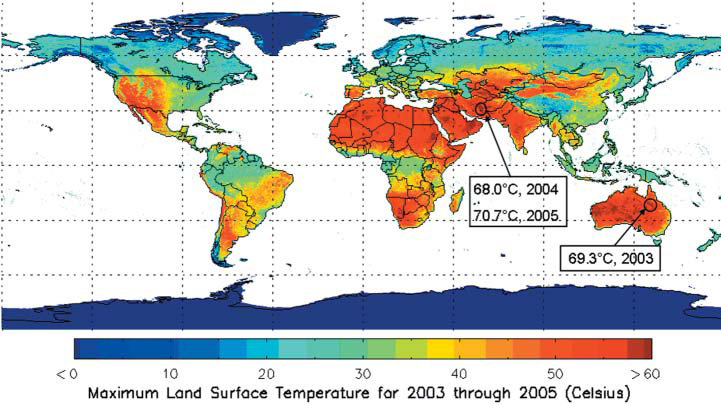

Editor’s note: Thanks to Chris Still for pointing out that El Azizia is no longer considered the earth’s hottest spot. Chris referred me to an article in EOS about land surface temperature (as opposed to air temperature) measurements from a satellite-based product mostly developed in ICESS by Z. Wan and colleagues, the MODIS Land Surface Temperature product: “In 2003, the hottest land surface temperature detected on the Earth’s surface was 69.3°C, in Queensland, Australia …In 2004, the hottest spot on the Earth’s surface was 68.0°C, in the Lut desert of Iran’s Kerman Province” (source).

Thanks also to Jon Eidelson who wrote in to point out that Tomkins was not the original source regarding Goleta’s “Great Simoon”; the earliest reference was in “Coast Pilot of California, Oregon, and Washington Territory,” by George Davidson, 1869, page 21. Like Tomkins, Davidson fails to cite any evidence for the event. Davidson was president of the California Academy of Sciences from 1871 to 1887, Honorary Professor of Geodesy and Astronomy and Regent of the University of California from 1877 to 1885, and the first professor of Geography at the University of California, Berkeley (Chair 1898-1905).

“History: gossip well told.” ~ Elbert Hubbard, The Roycroft Dictionary.

Article by Bill Norrington