How ancient societies understood and visualized the world — from their immediate surroundings to the edges of their empires and beyond — provides a unique perspective on their political and cultural values and philosophy, as well as demonstrating their mathematical and scientific expertise. New York University’s Institute for the Study of the Ancient World is hosting a major exhibition devoted to the subject, October 4 – January 5:

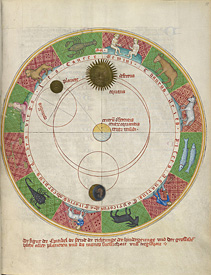

“Measuring and Mapping Space will explore the ways in which ancient Greek and Roman societies understood, perceived, and visualized both the known and the unknown areas of their world. It brings together more than forty objects, combining ancient artifacts with Medieval and Renaissance manuscripts and printed books that draw upon ancient geographic treatises. Together, they provide a fascinating overview of Greco-Roman theories of the shape and size of the Earth, ancient methods of surveying and measuring land, and the ways in which geography was used in Roman political propaganda. A specially designed multimedia display examines the increasing importance of modern technologies in mapping the ancient world” (Ibid.).

According to the Introduction to the Exhibition, “Measuring and Mapping Space: Geographic Knowledge in Greco-Roman Antiquity continues ISAW’s innovative approach to the ancient world with a selection of objects that help viewers understand how Greek and Roman conceptions of the world were reflected in and defined by how it was presented in globes, maps, and other tools of navigation and representation. A digital component of the exhibition—accessible both in the gallery space itself and on the world-wide web—extends the show’s reach to embrace continuing scholarly engagement with geographical aspects of antiquity.

The conceptualization of the ancient Greek and Roman universe was first formulated in the sixth century BCE by pre-Socratic philosophers interested in exploring the phenomena that regulated the external world. These geographic theories were further developed during the Hellenistic period and were later adopted and implemented by Roman geographers.

In studying the shape and size of the Earth, ancient geographers developed the fundamentals of topography and cartography, the sciences of recording the surface of the terrain through drawings, as we still know them today. In particular, Roman surveyors introduced the concepts of measurable and measured space, and the visualization of the terrain through lines of demarcation. Their work became instrumental for administrators and generals whose main goal was to control and exploit the expanse of lands.

Our modern knowledge of ancient cartography relies almost exclusively on written sources. Despite this paucity of ancient artifacts, it is clear that Greeks and Romans applied topographical studies to the mapping of land and sea routes, to the implementation of an accurate system of recording public and private lands, and to promote specific political agendas. In all these instances, the resulting representations of places presented the viewer with a distorted and schematized version of geographic and topographic elements, transforming those regions both on a conceptual and on a physical level.

In the exhibition, several artifacts and manuscripts illustrate the ways in which space was conceptualized not only through topography and cartography, but also according to non-geographical elements such as strategy and tactics. Indeed, official propaganda during the Roman imperial period consistently boosted the emperors’ agendas by performing acts of ‘imaginative geography’, out-and-out manipulations of known geographic facts that contributed to the creation of ever shifting social, ethnic, political, and cultural boundaries.

In addition to measuring, drawing and manipulating their known world, Greeks and Romans developed a flourishing literature of geographic mirabilia, in part inspired by the perceived secluded nature of their oikoumene. These texts, which had a wide impact on the shared geographic knowledge of individuals of all social categories, paired the knowledge of actual territories with hypothetical constructions of what existed beyond ancient ken, drawing both on actual facts from exploration and trade as well as pure fabrication. The objects on display show how geographical remoteness translated into projections of mythical and semi-mythical societies outside their controllable universe, ranging from the bizarre to the utopian” (source).

Editor’s note: Many thanks to Professor Helen Couclelis for suggesting this article. For more on the subject, see the New York Times article “The World as They Knew It: The Legacy of Greco-Roman Mapmaking.”