“Hydraulic fracturing in the United States began in 1949. According to the US Department of Energy, as of 2013 at least two million oil and gas wells in the US have been hydraulically fractured, and currently about 95% of completed oil and gas wells in the US are being hydraulically fractured. Hydraulically fractured wells make up 43% of the oil and 67% of the current natural gas production in the United States. Environmental safety and health concerns about hydraulic fracturing emerged in the 1980s, and are still being debated at the state and federal levels” (Wikipedia: Hydraulic fracturing in the United States).

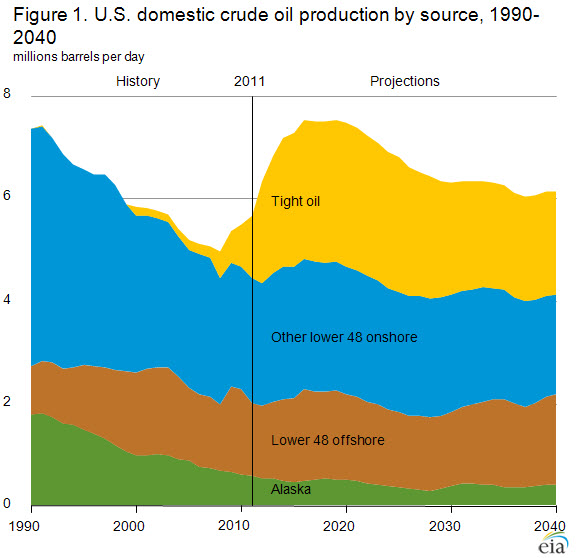

The National Petroleum Council estimates that hydraulic fracturing will eventually account for nearly 70% of natural gas development in North America. Hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling apply the latest technologies and make it commercially viable to recover shale gas and oil. In the United States, 45% of domestic natural gas production and 17% of oil production would be lost within 5 years without usage of hydraulic fracturing.

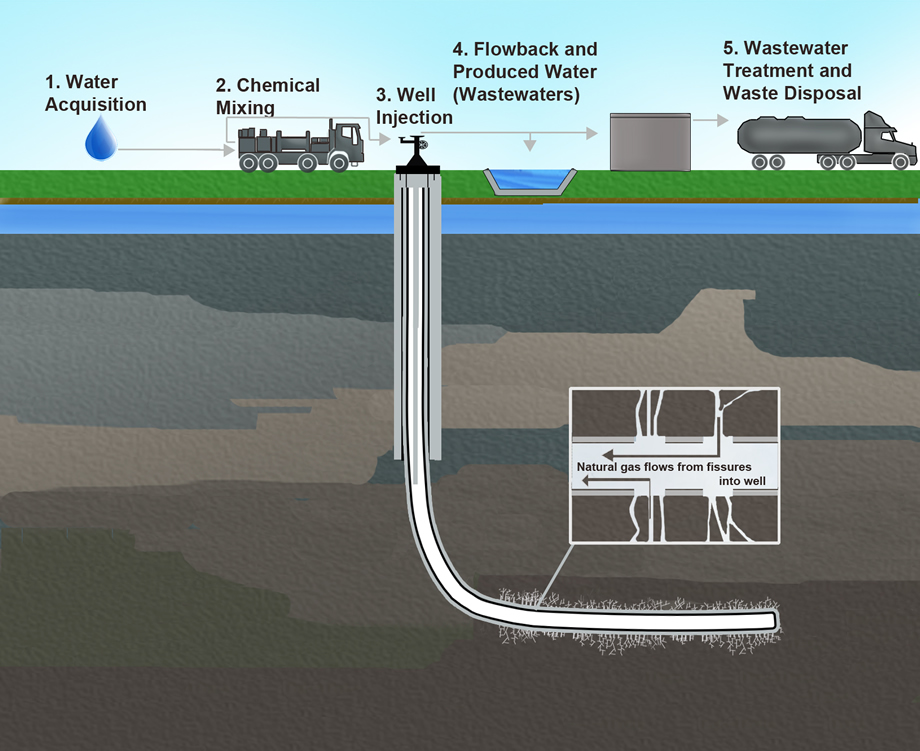

Hydraulic fracturing, better known as fracking, is a process that involves injecting mixtures of sand, water, and chemicals at high pressure in order to fracture shale rocks, thereby freeing oil and natural gas trapped deep underground. Currently, there are over half a million gas wells using this technique in the U.S., and each well requires about 8 million gallons of water per fracking. The fracking fluid contains up to 600 chemicals, including known carcinogens and toxins, and there are major concerns that they can leach out from the fracking sites and contaminate nearby groundwater. To date, there have been over 1,000 documented cases of water contamination next to areas of gas drilling. Furthermore, the recovered fracturing fluid is left to evaporate in open air pits, creating concern about the volatile organic compounds that are released into the atmosphere (source).

To complicate the issue, “The rivers of water pumped into and out of the ground during the production of natural gas, oil and geothermal energy are causing the Earth to shake more frequently in areas where these industrial activities are soaring, according to a series of studies … While the gas extraction process known as hydraulic fracturing (aka “fracking”) causes some small quakes, it’s the disposal of wastewater following that process — and many others relating to energy production — that lead to the largest tremors … Within the central and Eastern United States, more than 300 earthquakes of magnitude 3 or greater were recorded from 2010 through 2012, compared to an average rate of 21 earthquakes per year from 1967 to 2000, [according to] a review study on human-induced earthquakes published in Science” (source).

Cliff Frohlich, a seismologist from the University of Texas, hypothesizes that quakes occur when a “suitably oriented” fault lies near an injection site. “Hydraulic fracturing almost never causes true earthquakes,” he told the group gathered for the National Research Council workshop on Marcellus shale-gas drilling. “It is the disposal of fluids that is a concern.” Texas has 10,000 injection wells, Frohlich said, and some have been in use since the 1930s. That effectively makes the state a giant research lab for the shale-gas drilling issues now facing Appalachian states including West Virginia, Pennsylvania, Ohio, and New York. If injection wells were “hugely dangerous,” he said, “we would know.” “Texas would be famous as a state that just rocks with major earthquakes,” Frohlich said. “That is not true” (source).

Nonetheless, concerns about groundwater and air pollution, the sheer amount of water involved, and the possibility of earthquakes related to fracking have led many U.S. towns and states, and some entire countries, to put restrictions on fracking or even ban it until more research is done (see “List of Bans Worldwide”). On September 11, 2013, a controversial bill that would impose California’s first regulations on fracking and other oil production practices passed the state Assembly, despite opposition from oil companies as well as environmentalists, and California Governor Jerry Brown has promised to sign it into law if, as is expected, it is passed by the California Senate later this week.

“There are still many unanswered questions about the use and impacts of fracking and acidizing, and it is in the interest of all Californians to monitor and regulate these practices,” said state Senator Fran Pavley, an Aurora Hills Democrat who wrote the bill, SB 4. “Ultimately the oil industry, not the public, should be held accountable for the costs of these activities.” The bill was opposed by oil company interests in the state, which said it could make it difficult for California to reap the benefits offered by development of the Monterey Shale, including thousands of new jobs, increased tax revenue, and higher incomes for residents in one of the poorest regions in the nation. The bill was opposed by environmental groups that wanted to see an outright ban on fracking in the state. They were especially critical of amendments added to the bill late last week that they said would cut some existing requirements for environmental review” (source).

Article by Bill Norrington

.png)