“An ancient meteorite and high-energy X-rays have helped scientists conclude a half century of effort to find, identify, and characterize a mineral that makes up 38 percent of the Earth.” Tona Kunz, in an article for the Argonne National Laboratory, dated December 11, 2014 and with the title above, goes on to say:

And in doing so, a team of scientists led by Oliver Tschauner, a mineralogist at the University of Las Vegas, clarified the definition of the Earth’s most abundant mineral – a high-density form of magnesium iron silicate, now called Bridgmanite – and defined estimated constraint ranges for its formation. Their research was performed at the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility located at DOE’s Argonne National Laboratory.

The mineral was named after 1946 Nobel laureate and pioneer of high-pressure research Percy Bridgman. The naming does more than fix a vexing gap in scientific lingo; it also will aid our understanding of the deep Earth.

To determine the makeup of the inner layers of the Earth, scientists need to test materials under extreme pressure and temperatures. For decades, scientists have believed a dense perovskite structure makes up 38 percent of the Earth’s volume, and that the chemical and physical properties of Bridgmanite have a large influence on how elements and heat flow through the Earth’s mantle. But since the mineral failed to survive the trip to the surface, no one has been able to test and prove its existence – a requirement for getting a name by the International Mineralogical Association.

Shock-compression that occurs in collisions of asteroid bodies in the solar system create the same hostile conditions of the deep Earth – roughly 2,100 degrees Celsius (3,800 degrees Farenheit) and pressures of about 240,000 times greater than sea-level air pressure. The shock occurs fast enough to inhibit the Bridgmanite breakdown that takes place when it comes under lower pressure, such as the Earth’s surface. Part of the debris from these collisions falls on Earth as meteorites, with the Bridgmanite “frozen” within a shock-melt vein. Previous tests on meteorites using transmission electron microscopy caused radiation damage to the samples and incomplete results.

So the team decided to try a new tactic: non-destructive micro-focused X-rays for diffraction analysis and novel fast-readout area-detector techniques. Tschauner and his colleagues from Caltech and the http://www.gsecars.uchicago.edu/ GeoSoilEnviroCARS, a University of Chicago-operated X-ray beamline at the APS at Argonne National Laboratory, took advantage of the X-rays’ high energy, which gives them the ability to penetrate the meteorite, and their intense brilliance, which leaves little of the radiation behind to cause damage.

The team examined a section of the highly shocked L-chondrite meteorite Tenham, which crashed in Australia in 1879. The GSECARS beamline was optimal for the study because it is one of the nation’s leading locations for conducting high-pressure research.

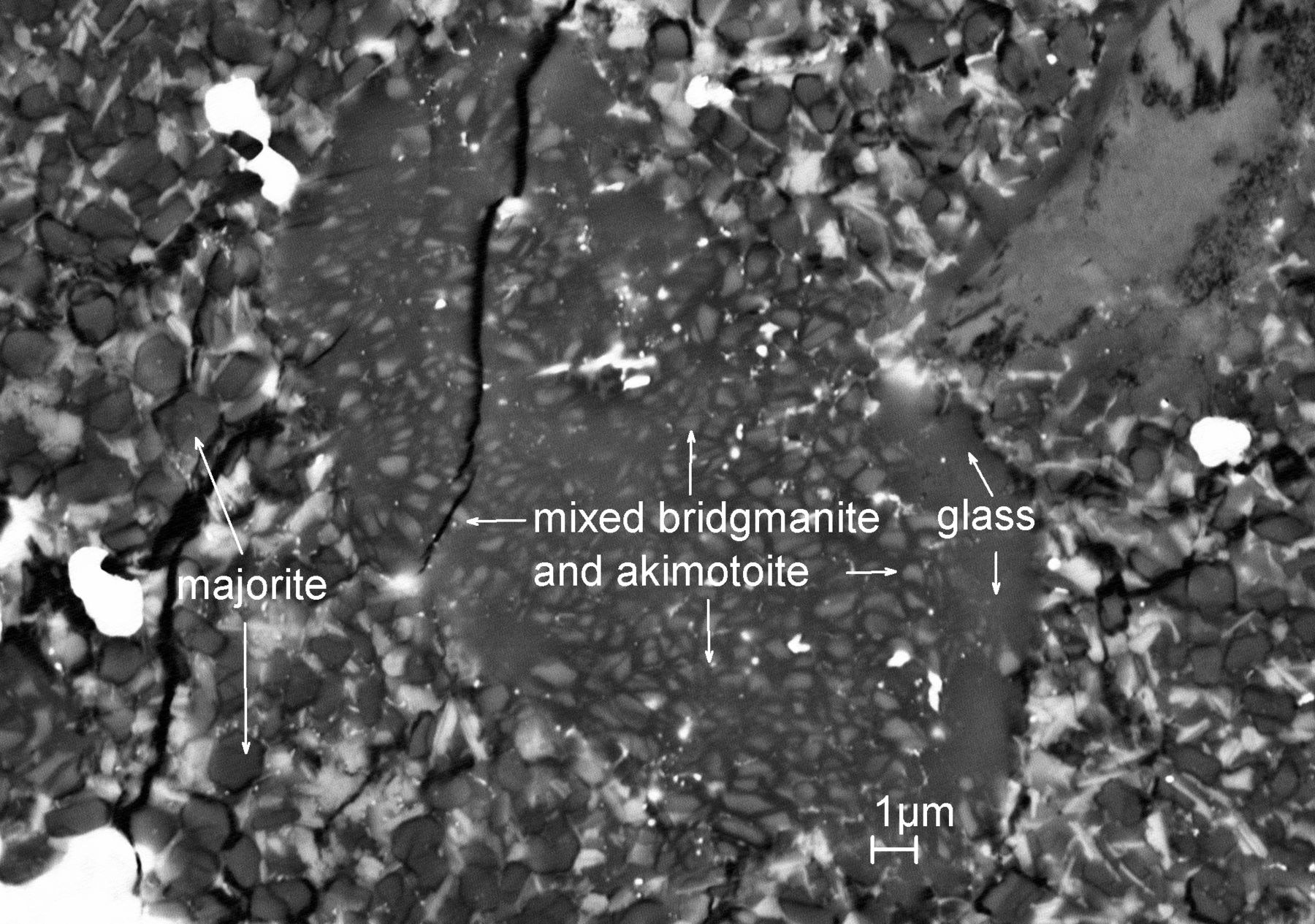

Bridgmanite grains are rare in the Tenhma meteorite, and they are smaller than 1 micrometer in diameter. Thus the team had to use a strongly focused beam and conduct highly spatially resolved diffraction mapping until an aggregate of Bridgmanite was identified and characterized by structural and compositional analysis.

This first natural specimen of Bridgmanite came with some surprises: It contains an unexpectedly high amount of ferric iron, beyond that of synthetic samples. Natural Bridgmanite also contains much more sodium than most synthetic samples. Thus the crystal chemistry of natural Bridgmanite provides novel crystal chemical insights. This natural sample of Bridgmanite may serve as a complement to experimental studies of deep mantle rocks in the future.

Prior to this study, knowledge about Bridgmanite’s properties has only been based on synthetic samples because it only remains stable below 660 kilometers (410 miles) depth at pressures of above 230 kbar (23 GPa). When it is brought out of the inner Earth, the lower pressures transform it back into less dense minerals. Some scientists believe that some inclusions on diamonds are the marks left by Bridgmanite that changed as the diamonds were unearthed.

The team’s results were published in the November 28 issue of the journal Science as “Discovery of bridgmanite, the most abundant mineral in Earth, in a shocked meteorite,” by O. Tschauner at University of Nevada in Las Vegas, N.V.; C. Ma; J.R. Beckett; G.R. Rossman at California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, Calif.; C. Prescher; V.B. Prakapenka at University of Chicago in Chicago, IL. This research was funded by the U.S. Department of Energy, NASA, and NSF.