“Dead reckoning is the process of estimating one’s current position based upon a previously determined position, or fix, and advancing that position based upon known or estimated speeds over elapsed time, and course. While traditional methods of dead reckoning are no longer considered primary means of navigation, modern inertial navigation systems, which also depend upon dead reckoning, are very widely used. A disadvantage of dead reckoning is that, since new positions are calculated solely from previous positions, the errors of the process are cumulative, so the error in the position fix grows with time” (Wikipedia). The following is taken verbatim from the online U.S. Naval History and Heritage pages, as cited below:

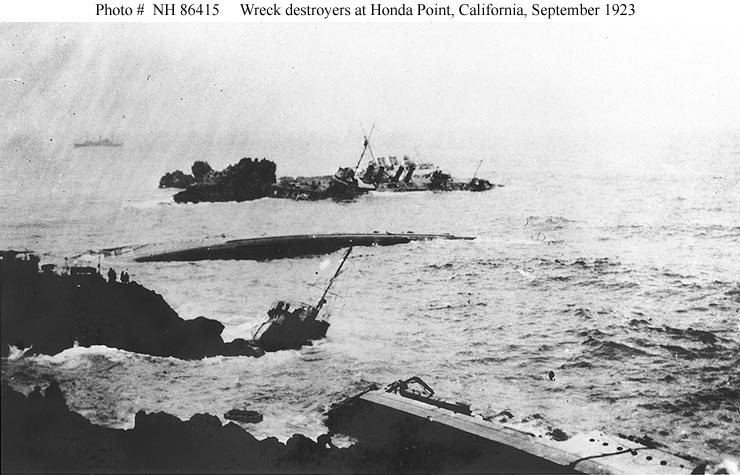

The Navy’s greatest navigational tragedy took place in September 1923 at an isolated California coastal headland locally known as Honda Point. Officially called Point Pedernales, Honda is a few miles from the northern entrance of the heavily-traveled Santa Barbara Channel. Completely exposed to wind and wave, and often obscured by fog, this rocky shore has claimed many vessels, but never more at one stroke than at about 9 PM on the dark evening of 8 September 1923, when seven nearly new U.S. Navy destroyers and twenty-three lives were lost there.

Just over twelve hours earlier Destroyer Squadron ELEVEN left San Francisco Bay and formed up for a morning of combat maneuvers. In an important test of engineering efficiency, this was followed by a twenty-knot run south, including a night passage through the Santa Barbara Channel. In late afternoon the fourteen destroyers fell into column formation, led by their flagship, USS Delphy. Poor visibility ensured that squadron commander Captain Edward H. Watson and two other experienced navigators on board Delphy had to work largely by the time-honored, if imprecise, technique of dead reckoning. Soundings could not be taken at twenty knots, but they checked their chartwork against bearings obtained from the radio direction finding (RDF) station at Point Arguello, a few miles south of Honda. At the time they expected to turn into the Channel, the Point Arguello station reported they were still to the northward. However, RDF was still new and not completely trusted, so this information was discounted, and DesRon 11 was ordered to turn eastward, with each ship following Delphy.

However, the Squadron was actually several miles north, and further east, than Delphy’s navigators believed. It was very dark, and almost immediately the ships entered a dense fog. About five minutes after making her turn, Delphy slammed into the Honda shore and stuck fast. A few hundred yards astern, USS S.P. Lee saw the flagship’s sudden stop and turned sharply to port, but quickly struck the hidden coast to the north of Delphy. Following her, USS Young had no time to turn before she ripped her hull open on submerged rocks, came to a stop just south of Delphy and rapidly turned over on her starboard side. The next two destroyers in line, Woodbury and Nicholas, turned right and left respectively, but also hit the rocks. Steaming behind them, USS Farragut backed away with relatively minor damage, USS Fuller piled up near Woodbury, USS Percival and Somers both narrowly evaded the catastrophe, but USS Chauncey tried to rescue the men clinging to the capsized Young and herself went aground nearby. The last four destroyers, Kennedy, Paul Hamilton, Stoddert and Thompson successfully turned clear of the coast and were unharmed. In the darkness and fog enveloping the seven stranded ships, several hundred crewmen were suddenly thrown into a battle for survival against crashing waves and a hostile shore (source).

For the hundreds of shipwrecked crewmen on board the seven destroyers, the immediate situation ranged from uncomfortable to nearly catastrophic. Nobody knew where they were, the best estimate being San Miguel island, on the other side of the Santa Barbara Channel entrance, and everyone was stunned by the suddenness of the calamity. Off-duty Sailors came topsides ill-dressed for what awaited them: chilly air, damp fog and drenching waves breaking over the ships. Oil, released from punctured fuel tanks, added to the misery, and to the danger. Most ships’ boiler and machinery spaces were flooded, extinguishing all electrical power. Darkness thus dominated nearly the entire area. Fortunately, disciplined crews were able to release steam before they abandoned their posts, preventing boiler explosions from compounding the tragedy.

On board Young, many men were swept away as the ship rolled over. Some were rescued or landed alive further down the coast, but twenty died in the water. With only inches of freeboard, waves easily swept over the wreck, threatening the rest of her crew as they clung to the now-horizontal port side, holding on to portholes broken open for the purpose or lashed to deck edge fittings. A particular terror was the sight of the oncoming Chauncey, seemingly bound for a collision. However, she went aground nearby, put her crew ashore with relative ease and soon became a route to safety for Young’s survivors. In a heroic swim, Chief Boatswain’s Mate Arthur Peterson carried a line from Young to Chauncey’s stern. One of the latter’s life rafts was then pulled back to the capsized destroyer, and some two-and-a-half hours after she was wrecked, all the men on Young had been brought over.

Woodbury, the only ship that retained power for more than a brief time, was firmly stuck near a little offshore islet. As a precaution, few men and a line were sent there while the ship tried to back free. Following over an hour of fruitless effort, her Captain decided to abandon ship, and the remainder of his crew hauled themselves along the line to the uncomfortable security of the islet, which was soon rechristened “Woodbury Rock”.

Settling fast on that rock’s outskirts, Fuller tried to send a whaleboat, and later a rubber raft, to rig a line between her bow and Woodbury, but this proved impossible. Swimmers finally established a connection to the as yet unchristened Woodbury Rock, to be followed by the rest of those on board Fuller. There they joined the Woodbury Sailors in trying to keep warm. All were rescued the next morning, most by the Santa Barbara fishing boat Bueno Amor de Roma (source).

Article by Bill Norrington