The following article, with the title above, is by Jennifer Zaino and was posted on semanticweb.com on February 2, 2012 under the heading of “Big Data, Government, Ontology/Ontologies, Scientific and Research Applications”:

How do you define a forest? How about deforestation? It sounds like it would be fairly easy to get agreement on those terms. But beyond the basics – that a definition for the first would reflect that a forest is a place with lots of trees and the second would reflect that it’s a place where there used to be lots of trees – it’s not so simple.

And that has consequences for everything from academic and scientific research to government programs. As explained by Krzysztof Janowicz, perfectly valid definitions for these and other geographic terms exist by the hundreds, in legal texts and government documents and elsewhere, and most of them don’t agree with each other. So, how can one draw good conclusions or make important decisions when the data informing those is all over the map, so to speak. “You cannot ask to show me a map of the forests in North America because the definition of forest differs between not just the U.S. and Canada but also between U.S. member states,” says Janowicz, Assistant Professor for geographic information science at UC Santa Barbara who’s one of the organizers of this week’s GeoVoCamp focusing on geo-ontology design patterns and bottom-up, data-driven semantics.

Or take the meaning of the word town as it is legally described in different states of the U.S. “Let’s say that in the U.S. you are interested in how rural economies react to global change. How do small places – what many colloquially understand as towns—that are not transitioned to a service infrastructure respond to a changing world,” he says. Having enough data isn’t the problem – there’s official data from the government, volunteer data, private organization data, and so on – but if you want to do a SPARQL query of it to discover all towns in the U.S., you’re going to wind up with results that include the places in Utah with populations of less than 5,000, and Los Angeles too – since California legally defines cities and towns as the same thing. “So this clearly blows up your data, because your analysis is you thinking that you are looking at small rural places,” he says.

This Big Data challenge is not a new problem for the geographic-information sciences community. But it is one that’s getting even more complicated, given the tremendous influx of more and more data from more and more sources: Satellite data, rich data in the form of audio and video, smart sensor network data, volunteer location data from efforts like the Citizen Science Project and services like Facebook Places and Foursquare. “The heterogeneity of data is still increasing. Semantic web tools would help you if you had the ontologies but we don’t have them,” he says. People have been trying to build top-level global ontologies for a couple of decades, but that approach hasn’t yet paid off, he thinks. There needs to be more of a bottom-up take: “The biggest challenge from my perspective is coming up with the rules systems and ontologies from the data.”

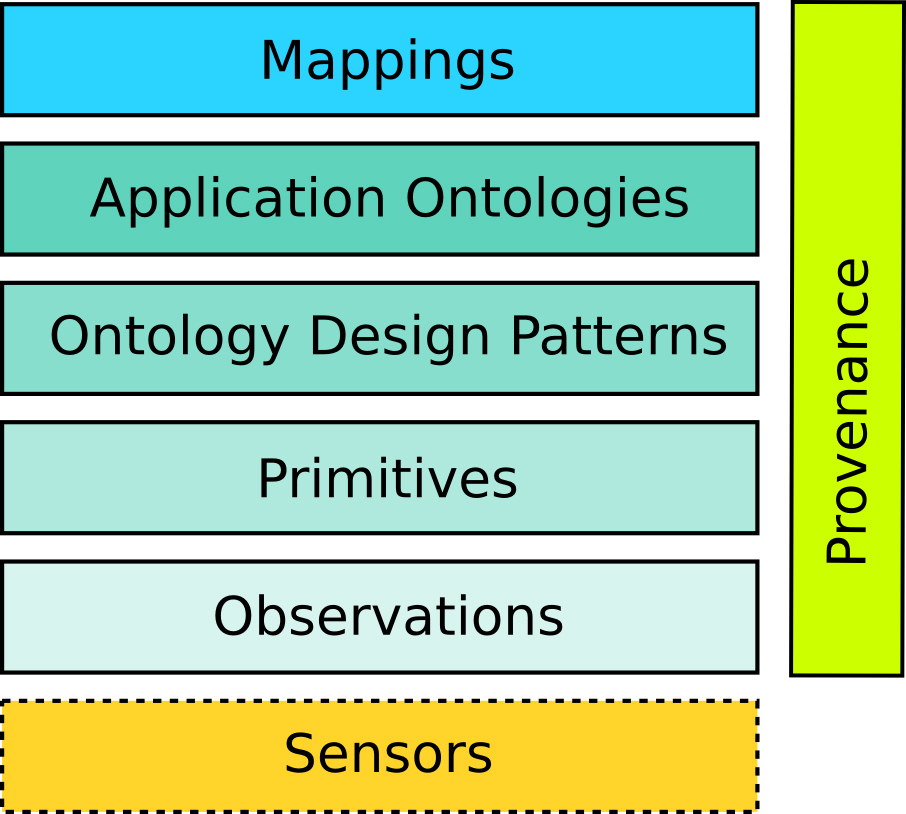

How to do it, he thinks, is to make very small and really local ontologies directly mined with the help of data mining or machine learning techniques, and then interlink them and use new kinds of reasoning to see how to reason in the presence of inconsistencies. “That approach is local ontologies that arrive from real application needs,” he says. “So we need ontologies and semantic web reasoning to have neater data that is human and also machine readable. And more effective querying based on analogy or similarity reasoning to find data sets that are relevant to our work and exclude data that may use the same terms but has different ontological assumptions underlying it.”

There is work underway in the area, including work he is researching around semantic signatures, for mining patterns out of observations data to create ontological primitives. The overall idea is to make the scientist him or herself the knowledge engineer – help these individuals derive the ontologies from their own data and give them the tools to map and combine their ontologies to share data. And thinking bigger to semantic interoperability of geographic data sets, why not take Al Gore’s Digital Earth idea further, to have an IBM Watson of the Digital Earth – “not information storage but way cooler, a Watson-like QA complex simulation system on top of Digital Earth. An interesting question is what kind of new interesting discoveries can we make on the way to that.”

Editor’s note: For more about Dr. Janowicz, see his web site; for more about this week’s GeoVoCamp, click here.