Mankind’s love of and quest for color in the form of pigments and dyes has motivated human aesthetics, exploration, exploitation, and experimentation since prehistoric times. The discovery of earth pigments and pigment grinding tools in an early Middle Stone Age deposit in Zambia suggests that early humans engaged in body and cave painting rituals as early as 400,000 years ago. The Egyptians were manufacturing pigments on a large scale by 4,000 BC, and the Chinese developed costly pigments such as Vermilion 2,000 years before it was rediscovered by the Romans.

Pigments are materials which change reflected light’s color because of wavelength absorption. They are generally classified as “natural” (organic) pigments—earth (e.g., ochres and iron oxides), mineral (usually made from ground-up, semi-precious stones, e.g., lapis lazuli used to make Ultramarine), and biological (for example, Tyrian Purple, made from whelks and Sepia, from cuttlefish)—or “synthetic” (inorganic) pigments (such as the nineteenth century aniline dyes, chemically produced from coal tar).

While the history of every pigment ever used by mankind has a fascinating geographical component, that of Carmine Red, also known as Cochineal, is particularly intriguing. The bright, red pigment was used by the Aztecs as early as the 10th century, it was exploited and monopolized by the Spanish for 300 years, its ingredients (crushed insects) were kept secret until the invention of the microscope and industrial espionage on the part of the French, and it is still used today in the textile, cosmetics, food, and medical research industries (though some of them also keep the ingredient secret).

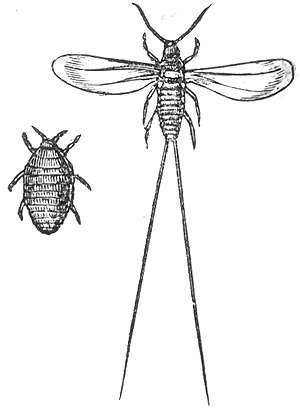

“The Cochineal (Dactylopius coccus) is a scale insect in the suborder Sternorrhyncha, from which the crimson-coloured dye carmine is derived. A primarily sessile parasite native to tropical and subtropical South America and Mexico, this insect lives on cacti from the genus Opuntia, feeding on plant moisture and nutrients. The insect produces carminic acid that deters predation by other insects. Carminic acid, which occurs as 17-24% of the weight of the dry insects, can be extracted from the insect’s body and eggs and mixed with aluminum or calcium salts to make carmine dye (also known as Cochineal)” (source).

When the Spanish invaded the New World in the 16th century, precious metals were the big draw—but it turned out that Cochineal became a main export, second only to silver. Cortez’s soldiers reported seeing great quantities of cochineal offered for sale in what today is Mexico City, and “there was immediate interest in this bright scarlet dye, for it was quickly recognized by the Spanish invaders as resembling the European red dye Kermes. Spain was interested in the possibility of Kermes being found in the New World, because it was not easily obtainable in the markets and dye shops of Europe” (source). Charles V ordered that samples be sent to Spain, and Cortez proceeded to establish a tribute system in Mexico for the pigment. By 1536, the royal Cochineal tribute amounted to 6,300 pounds of dye, and, when it was discovered that Cochineal was superior to Kermes and could be acquired in larger quantities by using cheaper labor, demand for the pigment ballooned and Cochineal became Spain’s second most profitable export item from the New World.

“The Spanish Cochineal industry thrived for over three hundred years. During that time, vast quantities of the red dye were shipped to Europe… [Recently] The Santa Maria de Yciar, a Spanish ship which had sunk with a full load in 1541, was discovered. Her cargo contained 20,000 pounds of Cochineal” (Dutton, Ibid.). To protect their lucrative monopoly, the Spanish fostered a misconception that Cochineal was a seed or grain, forbade the export of the Cochineal insects, and deterred other Europeans from visiting Mexico. “It was the invention of the microscope by van Leeuwenhoek that led to the discovery of the source of Cochineal dye. When, in 1704, a Cochineal particle was placed under the microscope, van Leeuwenhoek exclaimed that it was a bug… Despite the detective work of van Leeuwenhoek… Spain’s monopoly over Cochineal was not lost until, in 1777, a French naturalist… managed to enter Oaxaca secretly on foot, where he collected samples of both the cactus pads and the insect” (Ibid.).

The final demise of Spain’s Cochineal industry was due to the invention of superior (or, at least, much cheaper) synthetic alternatives in the middle of the 19th century: “Organic chemistry delivered the final blow for the cochineal color industry. When chemists created inexpensive substitutes for Carmine Red, an industry and a way of life went into steep decline… The demand for cochineal fell sharply with the appearance on the market of alizarin crimson and many other artificial dyes discovered in Europe in the middle of the 19th century, causing a significant financial shock in Spain as a major industry almost ceased to exist” (Wikipedia, Ibid.).

Today, the demand for Cochineal is rebounding to a degree, ironically because of the fact that many of its synthetic substitutes have proven to be carcinogenic. The history of pigments such as Cochineal is reminiscent of that of the Beaver in the fur trade or Cinnamon in the ancient spice routes, in terms of human aesthetics, exploration, exploitation, and experimentation. To quote the renowned French geographer Elisée Reclus, “Geography is history in space, whilst history is geography in time.”

Article by Bill Norrington