At present, there are 51 large wildfires burning in the U.S., the National Interagency Fire Center has raised the national wildfire preparedness level to the highest level for the first time in five years, and firefighting costs have reached $1.2 billion so far this year, more than half last year’s total of $1.9 billion and quickly nearing the 10-year average of $1.4 billion. There have been 33,000 fires that have burned more than 5,300 square miles — an area nearly the size of Connecticut. Some scientists are predicting that this year’s fire season will be the worst in over 100 years.

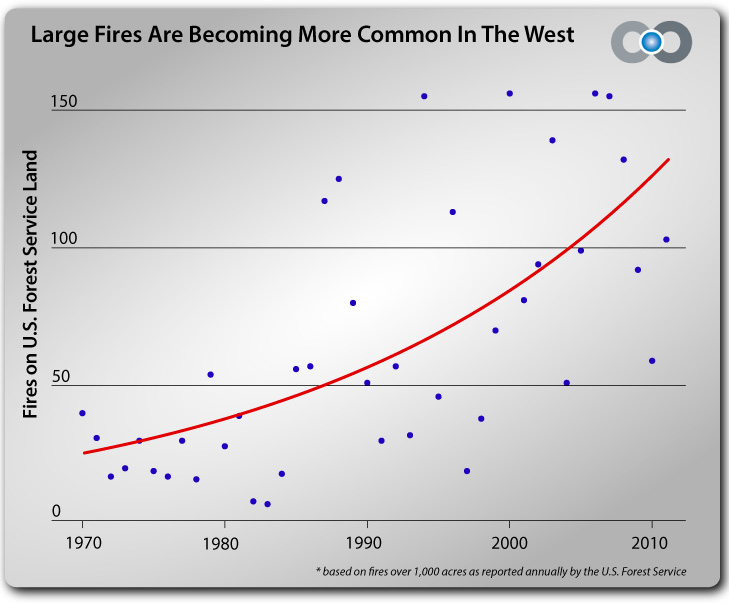

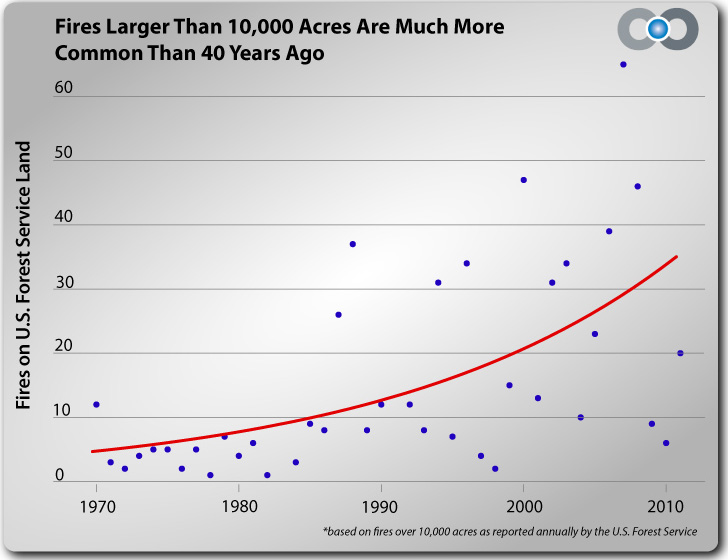

“There are more large fires (greater than 10,000 acres) burning now than at any time in the past 40 years, and the total area burned each year has also increased. And, in fact, the top eight worst wildfire years since 1960, in terms of acres burned, have all occurred since 2000, according to National Interagency Fire Center data. (You can monitor wildfires that are currently burning with Climate Central’s new interactive wildfires map.)

Many factors are involved in creating conditions that are primed for large wildfires. Decades of fire suppression strategies have left large tracts of forest with excess fuel to burn. Increased human development near traditionally fire-prone ecosystems has contributed to an uptick in damaging fires, and natural climate and weather variability plays a large role as well.

Climate studies show that over the long term, climate change is escalating wildfire risk in the West. According to Climate Central research, in some states, such as Idaho and Arizona, the number of large fires burning on U.S. Forest Service land each year has tripled or even quadrupled since the early 1970s. In other states, such as California and Wyoming, the number of large fires has doubled.

Idaho has seen the biggest increase in large wildfires since 1970 than any other western state. Year-to-year there is still a lot of variability, but in the past decade, several years with above-average temperatures and low spring snowpack have led to dozens of large wildfires on federal land.

Researchers predict that the area burned in the West may quadruple for every additional 1.8°F of average surface temperature rise. That is particularly ominous, since according to the most recent climate model projections contained in the draft U.S. National Climate Assessment, average temperatures could rise between 2°F and 4°F across most of the U.S. within the next few decades, and by as much as 8°F by 2100” (source).

“Fire seasons are starting earlier, due to warmer spring temperatures and earlier snow melt, and they are lasting longer into the fall. Snow cover shortens the fire season because dry vegetation is not a factor in fire ignition or progression. Rain will lead to build-up of grasses that dry out in the summer heat and become fuel for fires. “So while it may be warmer, it is the shift from snow to rain that increases fire risk,” said Jeff Eidenshink, fire science team lead with the USGS EROS facility.

“A 100,000-acre wildfire used to be unusual, you would see one every few years,” said Carl Albury, a contractor with the Forest Service-Remote Sensing and Applications Center in Salt Lake City. “Those type of fires are becoming a yearly occurrence.”

NASA recently launched the Landsat 8 and Suomi-NPP satellites, which will provide information on fire fuels, active fires, aerosols, and climate: all pieces of the wildfire puzzle” (source).

Article by Bill Norrington