“O Romeo, Romeo, wherefore art thou Romeo?” Although we use “wherefore,” if at all, as a synonym for “why,” Juliet uses the word in a more limited sense. By “wherefore?” Juliet means “for what purpose?” If she had merely asked “Why art thou Romeo?” she wouldn’t be distinguishing the two major meanings of “why”—”from what cause” (in the past) and “for what purpose” (in the future). “Wherefore” clearly emphasizes the latter sense, which is why “whys and wherefores” are different things. “Wherefore” and its partner “therefore” reflect the basic tendency of English to use spatial ideas—”where?” “there”—to represent logical ideas, such as cause and effect (Romeo And Juliet, Act 2, scene 2, 33–49; source).

Richard J. Pike, a geologist with the U. S. Geologic Survey, penned an article for The Professional Geographer back in 1974 titled “Why Not an Extraterrestrial Geography?” He opened the article by commenting that: “The number of planetary surfaces open to detailed investigation tripled during the last decade, thereby changing the earth sciences forever. From the dearth of papers on extraterrestrial topics submitted to the 1972 International Geographical Congress, despite the specific call for such material, it is evident that the profession has not responded to this exciting development with any great enthusiasm. Rather, perhaps, geographers remain partial to one of the more widely circulated definitions of their field as ‘the totality of man in his environment.’ From this proposition and from the absence of permanent human settlement on extraterrestrial bodies follows the corollary that there can be no such thing as the geography of the Moon or the geography of Mars. For several reasons, this verdict is premature. First, such a parochial perspective is hardly appropriate to a profession whose scope traditionally has encompassed an entire planet. At worst, this attitude suggests that geographers are prepared to abandon completely the investigation of the lunar and martian surfaces to astronomers, geologists, and geophysicists. Such an unfortunate acquiescence would still further encourage those who would gladly transform geography entirely into spatial economics and human ecology, to the exclusion of its physical component. In fact, geographers face an unparalleled opportunity to broaden the scope of their field in general, to say nothing of their topical and regional specialties” (source).

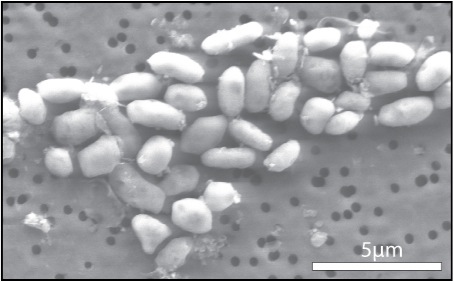

Closer to home, NASA’s highly anticipated December 2 announcement that it found microbes from Mono Lake in California that can use arsenic as one of the building blocks of their DNA is a discovery that may “fundamentally change the knowledge about what comprises all known life on Earth.” Furthermore, according to Dr. Felisa Wolfe-Simon, the lead scientist behind the research, “We’ve cracked open the door for what’s possible for life elsewhere in the universe, and that’s profound to understand how life is formed and where life is going.” “The results of this study will inform ongoing research in many areas, including the study of Earth’s evolution, organic chemistry, biogeochemical cycles, disease mitigation and Earth system research. These findings also will open up new frontiers in microbiology and other areas of research. ‘The definition of life has just expanded,’ said Ed Weiler, NASA’s associate administrator for the Science Mission Directorate at the agency’s Headquarters in Washington. ‘As we pursue our efforts to seek signs of life in the solar system, we have to think more broadly, more diversely and consider life as we do not know it’” (source). Add to this another recent discovery that the number of stars in the universe might be triple that of previous estimates, and the definition and, indeed, the “wherefore,” of Geography has just expanded as well.

Article by Bill Norrington

“O Romeo, Romeo, wherefore art thou Romeo?” Although we use “wherefore,” if at all, as a synonym for “why,” Juliet uses the word in a more limited sense. By “wherefore?” Juliet means “for what purpose?” If she had merely asked “Why art thou Romeo?” she wouldn’t be distinguishing the two major meanings of “why”—”from what cause” (in the past) and “for what purpose” (in the future). “Wherefore” clearly emphasizes the latter sense, which is why “whys and wherefores” are different things. “Wherefore” and its partner “therefore” reflect the basic tendency of English to use spatial ideas—”where?” “there”—to represent logical ideas, such as cause and effect (http://www.enotes.com/romeo-and-juliet-text/act-ii-scene-ii#rom-2-2-35 Romeo And Juliet Act 2, scene 2, 33–49)

Richard J. Pike, a geologist with the U. S. Geologic Survey, penned an article for The Professional Geographer back in 1974 titled “Why Not an Extraterrestrial Geography?” He opened the article by commenting that: “The number of planetary surfaces open to detailed investigation tripled during the last decade, thereby changing the earth sciences forever. From the dearth of papers on extraterrestrial topics submitted to the 1972 International Geographical Congress, despite the specific call for such material, it is evident that the profession has not responded to this exciting development with any great enthusiasm. Rather, perhaps, geographers remain partial to one of the more widely circulated definitions of their field as ‘the totality of man in his environment.’ From this proposition and from the absence of permanent human settlement on extraterrestrial bodies follows the corollary that there can be no such thing as the geography of the Moon or the geography of Mars. For several reasons, this verdict is premature. First, such a parochial perspective is hardly appropriate to a profession whose scope traditionally has encompassed an entire planet. At worst, this attitude suggests that geographers are prepared to abandon completely the investigation of the lunar and martian surfaces to astronomers, geologists, and geophysicists. Such an unfortunate acquiescence would still further encourage those who would gladly transform geography entirely into spatial economics and human ecology, to the exclusion of its physical component. In fact, geographers face an unparalleled opportunity to broaden the scope of their field in general, to say nothing of their topical and regional specialties.

Closer to home, NASA’s highly anticipated December 2 announcement that it found microbes from Mono Lake in California that can use arsenic as one of the building blocks of their DNA is a discovery that may “fundamentally change the knowledge about what comprises all known life on Earth.” Furthermore, according to Dr. Felisa Wolfe-Simon, the lead scientist behind the research, “We’ve cracked open the door for what’s possible for life elsewhere in the universe, and that’s profound to understand how life is formed and where life is going.” “The results of this study will inform ongoing research in many areas, including the study of Earth’s evolution, organic chemistry, biogeochemical cycles, disease mitigation and Earth system research. These findings also will open up new frontiers in microbiology and other areas of research. ‘The definition of life has just expanded,’ said Ed Weiler, NASA’s associate administrator for the Science Mission Directorate at the agency’s Headquarters in Washington. ‘As we pursue “O Romeo, Romeo, wherefore art thou Romeo?” Although we use “wherefore,” if at all, as a synonym for “why,” Juliet uses the word in a more limited sense. By “wherefore?” Juliet means “for what purpose?” If she had merely asked “Why art thou Romeo?” she wouldn’t be distinguishing the two major meanings of “why”—”from what cause” (in the past) and “for what purpose” (in the future). “Wherefore” clearly emphasizes the latter sense, which is why “whys and wherefores” are different things. “Wherefore” and its partner “therefore” reflect the basic tendency of English to use spatial ideas—”where?” “there”—to represent logical ideas, such as cause and effect (http://www.enotes.com/romeo-and-juliet-text/act-ii-scene-ii#rom-2-2-35 Romeo And Juliet Act 2, scene 2, 33–49). Richard J. Pike, a geologist with the U. S. Geologic Survey, penned an article for The Professional Geographer back in 1974 titled “Why Not an Extraterrestrial Geography?” He opened the article by commenting that: “The number of planetary surfaces open to detailed investigation tripled during the last decade, thereby changing the earth sciences forever. From the dearth of papers on extraterrestrial topics submitted to the 1972 International Geographical Congress, despite the specific call for such material, it is evident that the profession has not responded to this exciting development with any great enthusiasm. Rather, perhaps, geographers remain partial to one of the more widely circulated definitions of their field as ‘the totality of man in his environment.’ From this proposition and from the absence of permanent human settlement on extraterrestrial bodies follows the corollary that there can be no such thing as the geography of the Moon or the geography of Mars. For several reasons, this verdict is premature. First, such a parochial perspective is hardly appropriate to a profession whose scope traditionally has encompassed an entire planet. At worst, this attitude suggests that geographers are prepared to abandon completely the investigation of the lunar and martian surfaces to astronomers, geologists, and geophysicists. Such an unfortunate acquiescence would still further encourage those who would gladly transform geography entirely into spatial economics and human ecology, to the exclusion of its physical component. In fact, geographers face an unparalleled opportunity to broaden the scope of their field in general, to say nothing of their topical and regional specialties. Closer to home, NASA’s highly anticipated December 2 announcement that it found microbes from Mono Lake in California that can use arsenic as one of the building blocks of their DNA is a discovery that may “fundamentally change the knowledge about what comprises all known life on Earth.” Furthermore, according to Dr. Felisa Wolfe-Simon, the lead scientist behind the research, “We’ve cracked open the door for what’s possible for life elsewhere in the universe, and that’s profound to understand how life is formed and where life is going.” “The results of this study will inform ongoing research in many areas, including the study of Earth’s evolution, organic chemistry, biogeochemical cycles, disease mitigation and Earth system research. These findings also will open up new frontiers in microbiology and other areas of research. ‘The definition of life has just expanded,’ said Ed Weiler, NASA’s associate administrator for the Science Mission Directorate at the agency’s Headquarters in Washington. ‘As we pursue our efforts to seek signs of life in the solar system, we have to think more broadly, more diversely and consider life as we do not know it’” (http://www.nasa.gov/topics/universe/features/astrobiology_toxic_chemical.html source). Add to this another recent discovery that the number of stars in the universe might be triple current estimates, and the definition and, indeed, the “wherefore,” of Geography has just expanded, as well. our efforts to seek signs of life in the solar system, we have to think more broadly, more diversely and consider life as we do not know it’” (http://www.nasa.gov/topics/universe/features/astrobiology_toxic_chemical.html source). Add to this another recent discovery that the number of stars in the universe might be triple current estimates, and the definition and, indeed, the “wherefore,” of Geography has just expanded, as well.