Alumnus Alex Samarin (BA 2008) recently wrote to say: “I think it’d be great if you could feature a current environmental issue that I’ve been a part of: groundwater contamination by oil extraction. It’s an important issue in California that was just heard by the CA Senate Natural Resources committee on Tuesday [March 10]. My dad and I have been involved at the local level by pursuing a particular case of legal infraction in Tulare County near my family’s home. My father approached the Natural Resource Defense Council for legal counsel, and I made maps to prove the case. This blog post by a Natural Resources Defense Council geologist highlights our case (“Hundreds of Active Oil Waste Injection Wells Still Threaten Drinking Water across California,” March 9, 2015):

California regulators shut down 12 injection wells last week that were improperly permitted to pump potentially toxic oil and gas waste water into drinking water aquifers. One of the 12 shutdown wells is in the Deer Creek Oil Field, near the town of Terra Bella, CA. Active since 2002, that well has injected almost 80 million gallons of waste into federally protected, very high-quality drinking water. The field also contains six more active disposal wells, still injecting into the same formation. Houses and farms surround the oil field.

Last fall NRDC was contacted by Bill Samarin, a resident of Terra Bella, who was concerned that the waste injection wells at the Deer Creek field could be contaminating groundwater. He noted that these injection wells are very shallow and explained that people near the oil field get water from private wells – wells that he feared could be pulling up water contaminated by oil waste.

At the time, one of the operators of the Deer Creek field was applying for a Special Use Permit (SUP) that could increase the amount of waste being pumped into six of the seven existing injection wells. Mr. Samarin sent us a detailed timeline of all the state and local officials he’d met with to express his concern about these wells and the proposal to increase the amount of waste pumped into them. According to Mr. Samarin, he was told that the field was operating in compliance with regulations. Not convinced, he filed an appeal of the SUP with the Tulare County Board of Supervisors (BOS) and reached out to NRDC for help.

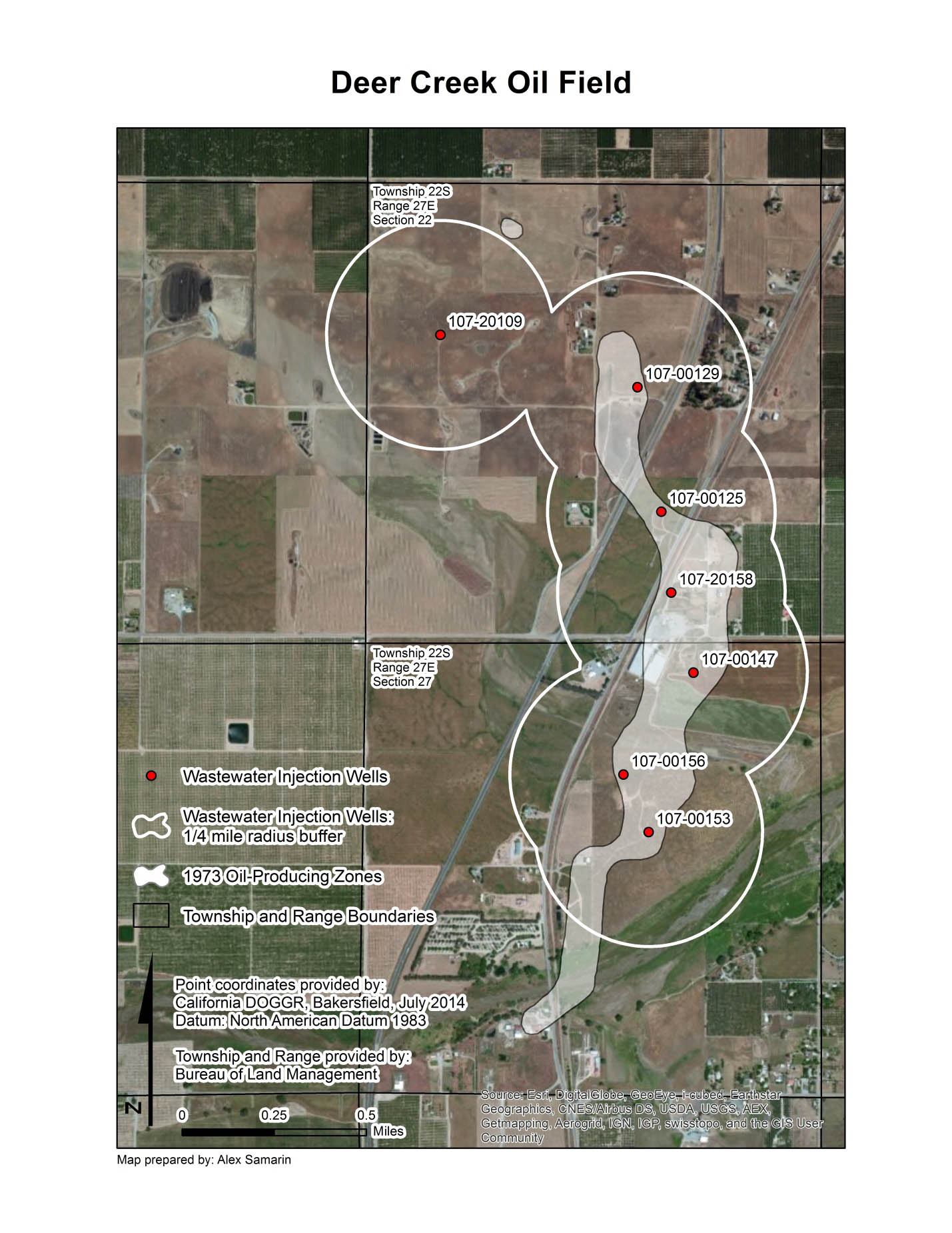

For months, Mr. Samarin had been collecting all the data he could get his hands on about the oil field. Among other things, he learned that the drinking water these wells were pumping waste into had been granted an “aquifer exemption,” which essentially turned this high-quality drinking water aquifer into a sacrifice zone, legally allowing oil and gas waste to be injected into it. He enlisted the help of his son Alex Samarin, a geographer, to make a map displaying some of the information he had gathered. They discovered something shocking: the map showed that one of the injection wells was located outside the boundary of the aquifer exemption and was therefore injecting waste directly into protected drinking water.

Based on the available data, there was also concern that the injected waste could be migrating upwards into shallower drinking water and that the injection wells weren’t constructed properly and could be another pathway for oil waste to contaminate drinking water.

Armed with this and some help from NRDC, Mr. Samarin presented his case to the Tulare County BOS. Despite the damning evidence he provided, his appeal was denied and the oil company’s plan to stuff even more waste into the drinking water aquifer was upheld.

Mr. Samarin worked for months to bring this issue to light, only to be told that he was wrong, or crazy, or worse. He was finally vindicated last week when the State decided to shut down the injection well outside the aquifer exemption boundary, but the victory is far from complete. This is because the other worrying thing that Alex Samarin’s simple yet powerful map shows is that, while the other six wells are located within the exemption boundary, the fluids those wells are injecting may be migrating beyond it.

The map shows ¼-mile radius circles drawn around the injection wells, referred to as the “Area of Review” (AoR). Generally speaking, the AoR is the area around an injection well where drinking water may be endangered by injection activity. The use of a fixed, ¼-mile radius to represent the AoR has been heavily criticized as not being sufficiently protective of ground water, including criticism by the independent auditors who reviewed California’s injection well program in 2011 and by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s own scientists. The map shows that, even using this weak standard, the AoRs of the six remaining active injection wells at the Deer Creek oil field extend beyond the boundary of the exempt portion of the aquifer. Given how close the injection wells are to the exemption boundary, it’s a reasonable hypothesis that the fluids being injected are migrating into and potentially contaminating protected drinking water.

It’s also likely that Deer Creek Oil Field isn’t the only place in the state where this is happening. So, in addition to the 2,553 wells that DOGGR has identified as being located outside the boundaries of exempt aquifers, there could be hundreds or thousands more that are within the exemption boundaries, but where injected fluids could be migrating out. To be clear, that’s a violation of the rules too.

The scale and number of problems with California’s injection well program is overwhelming. We commend the State for taking the steps it has to begin fixing this mess, and for the additional steps to which it has committed itself. But a problem of this magnitude and severity demands an equally large and serious response, and in that we think the State is falling short. That is why we and others are continuing to call on the State to immediately shut down all 2,553 wells located outside the boundaries of exempt aquifers and to keep them shut down until full investigations of any water contamination – including that which may be caused by wells within the boundaries of exempt aquifers – is complete.

The primary mission of the injection well program is simple: to ensure that underground injection does not endanger drinking water. By nearly any imaginable measure, California has failed that goal.