“In 1807, President Thomas Jefferson established the Survey of the Coast to produce the nautical charts necessary for maritime safety, defense, and the establishment of national boundaries. Within years, the United States Coast Survey was the government’s leading scientific agency, charting coastlines and determining land elevations for the nation. In 1861, the agency adjusted quickly to meet the needs of a country at war.” Alumnus John Cloud (PhD, 2000), a Geographer, writer, and editor for the NOAA Central Library, has written an article that was recently web-published by the Office of Coast Survey within the National Ocean Service of NOAA, the lineal successor to the Coast Survey. As NOAA’s online History/Civil War Collection page points out, Dr. Cloud’s article, “The U.S. Coast Survey in the Civil War,” “provides insights into the innovative developments of the era,” and the following extracts are taken from that source. (John’s complete article can be found here.)

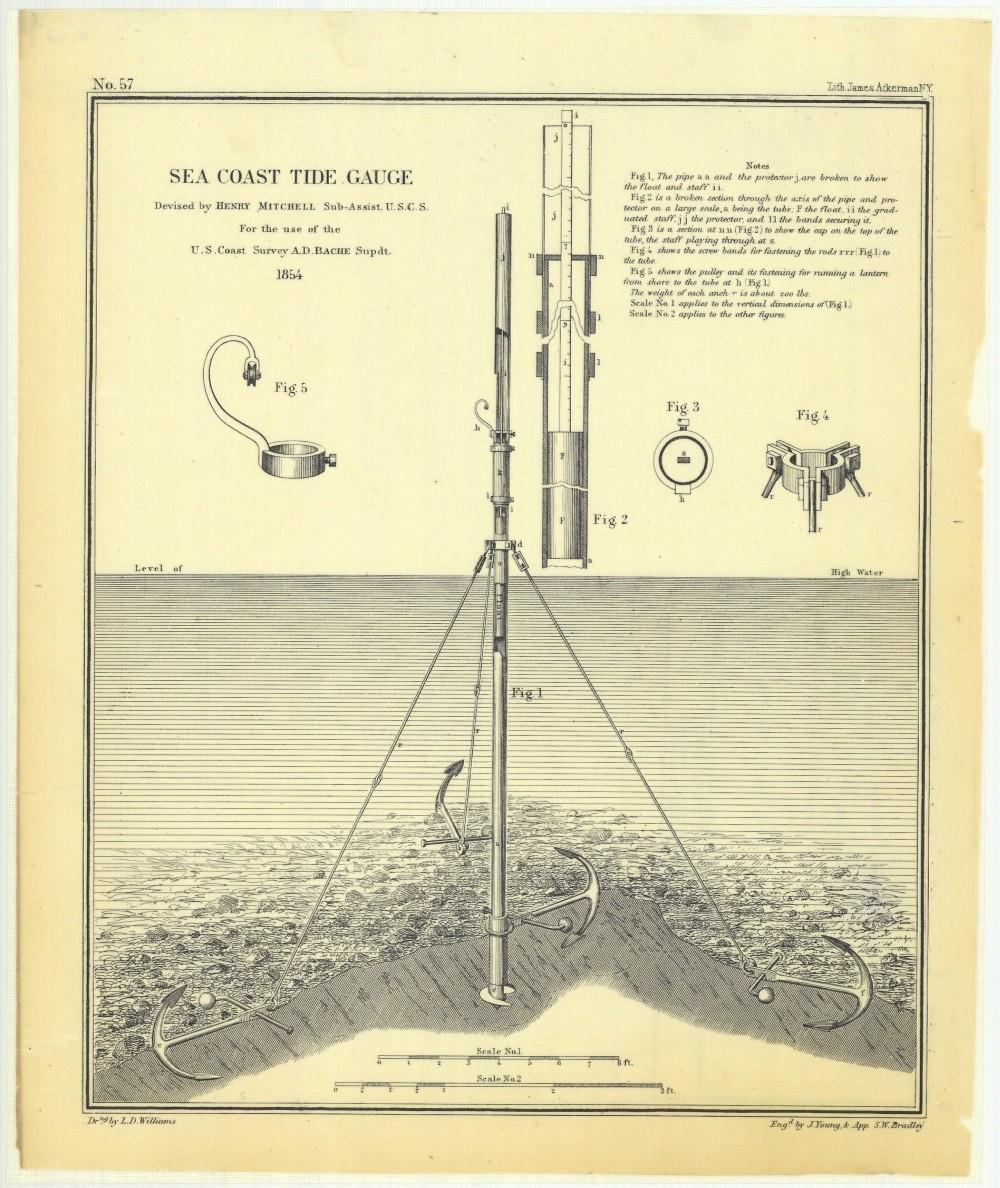

The U.S. Coast Survey began in 1807 as the Survey of the Coast, authorized by Congress and developed by President Thomas Jefferson. Alexander Dallas Bache (1806-1867) became the second Superintendent of the U.S. Coast Survey and remained its nominal leader until his death. Hence, the history of the Coast Survey in the Civil War is almost entirely under his leadership. Bache, the great grandson of Benjamin Franklin, was one of the major scientists of his era. He introduced telegraph use as a geodetic instrument, using it to determine differences in time of astronomical observations at different stations that correlated with differences in longitude. While Bache was not unique in this application, he developed the methodology that became standard, and the Survey’s technique became known in Europe as “the American method.” Bache also initiated major investigation of terrestrial magnetism, the changing geo-magnetic fields as sensed through local observations, which was critical to determining magnetic variation in compass needles in the field. That determination, in turn, was critical to every manner of military activity. Under Bache, the Survey developed new instruments to determine and measure tides and current which later became critical during the war. One notable example of that was Henry Mitchell’s seacoast tide gauge, a relatively small and quite portable instrument designed for use in the surf or in other bodies of moving water. In addition to pioneering the telegraph as a geodetic instrument, Bache also pioneered the use of steamships as hydrographic instruments.

To summarize these broad points, in the years under Bache before the war, the Survey and its associated military officers in both services gained a broad familiarity with many areas of the country, particularly the coastal areas of the southern states, where much of the Civil War would later be fought. They developed and invented or acquired new instruments, particularly emphasizing reduction in weight and size without impairing accuracy—instrument traits ideal for wartime applications. And, unlike the U.S. Navy, the Survey made the transition from sailing vessels to powered steamships well before the war, with important implications for their later military service.

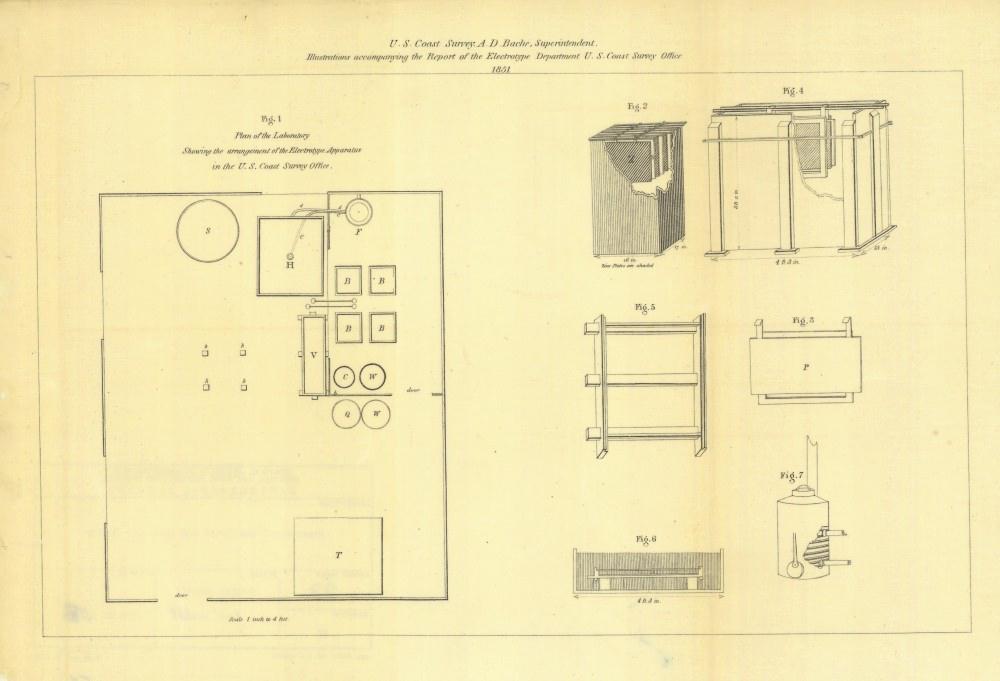

Superintendent Hassler was a progressive European who applied European instruments in the New World. His cartography was based on creating engraved copper plates used to produce limited numbers of wonderfully detailed but necessarily expensive maps and charts. His engravers worked for many years to create the set of six copper plates comprising the set of sheets of New York Bay and Harbor and the Environs. None of these were finished by the time of his untimely death in 1843. Superintendent Bache redoubled work on the plates, and published editions of the first four sheets in 1844. In 1845, his engravers completed the remaining two plates, and prepared a re-scaled and enlarged one-sheet version of the New York map. After that, Coast Survey cartography quickly developed. Bache wanted maps produced for parts of every one of the Survey’s new sections, and every year. He also wanted copies of these new maps readily distributed to Congressmen representing areas on the maps, and Congressmen who controlled his budget. And he genuinely wanted the largest quantities of the highest quality maps to be printed and distributed. In the 1840s, the process of electrotype plating was invented in Europe, and Bache brought in two highly skilled men to develop the electrotype system for the Survey.

The far-sighted Bache also realized a new technology – photography –would have a major impact on the Survey. In the early 1850s, he ordered the personnel in the Survey divisions to explore new methods for showing terrain by shaded relief in engraving. He also asked them to explore the potential applications of lithography for printing maps more cheaply and easily. This process began by developing methods to reproduce Survey engraved maps, which were printed on heavy, expensive paper. Lithographic copies, on the other hand, could be printed on cheaper and far thinner paper, which could be folded and then sewn into the massive volume of the annual report. And he asked them to explore methods to allow rapid transfer and rescaling of details from the Survey’s original unpublished manuscript maps, to their published maps. The key technology that would tie together these practices, from the field sheet in the country to the published chart in the office, was photography.

The first indication of the changes in the Coast Survey as war approached was the reduction in fieldwork on the Pacific coast. Both hydrographic and topographic survey parties returned steadily to the east, leaving a small field staff primarily working on completing the topographic surveys of San Francisco Bay. Map compilation and production based on previous fieldwork continued, but clearly, by 1858 the Survey was anticipating war on the Atlantic and Gulf coasts. In addition to the personnel turmoil and enemy harassment of his field parties, Bache faced onerous developments at home: Congress looked upon the operations of the Survey as expendable in the year 1861. A much-reduced Congressional allocation of funds for 1861-1862 led to curtailment of Coast Survey activities right at the time that operations should have been expanding in support of Union forces. This was followed by an attempt by the House of Representatives to eliminate the Coast Survey appropriation for 1862-1863. It is a tribute to Bache as an administrator that he was able to overcome the disruptions of early 1861 and further build and direct an organization that would play a major role in determining much of the strategy and tactics of the Civil War.

In January 1861, Bache finished and published the Survey’s annual report for the year 1860. The report made almost no mention of the gathering storm, apart from oblique statements about the rapid termination of certain survey parties here and there. But the report also included a small and subtle but rather extraordinary document. In the 1860 report, the backside of the Index of Sketches had glued to it a very small printed piece of paper. The small piece of paper notes that many of the maps and charts listed on the List of Sketches were not, in fact, bound in the volume. As the paper politely indicates: “It is deemed inexpedient at the present time, for obvious reasons, to publish for general circulation maps and charts Nos…” The ten charts covered coastal areas in the Mississippi Sound in the Gulf of Mexico, and coastal bays along the Florida coast and up the Atlantic coast to Chesapeake Bay. All charted areas were entirely the lands and waters of slave-holding states. At the very same moment, however, the Survey, while not publishing the maps for general circulation, was in fact quietly in the early stages of an extraordinary project to publish the very same maps, plus many others, but to do so secretly. The secret project featured the deliberately innocuous name of Notes on the Coast. The genesis of the project was the Blockade Strategy Board, which also had an innocuous name: “Conference on Commission.” This group organized to determine and deploy the Union naval strategy against the Rebellion, as they termed it. The seceding states controlled their territories, but they did not necessarily control the ocean adjacent to their shores.

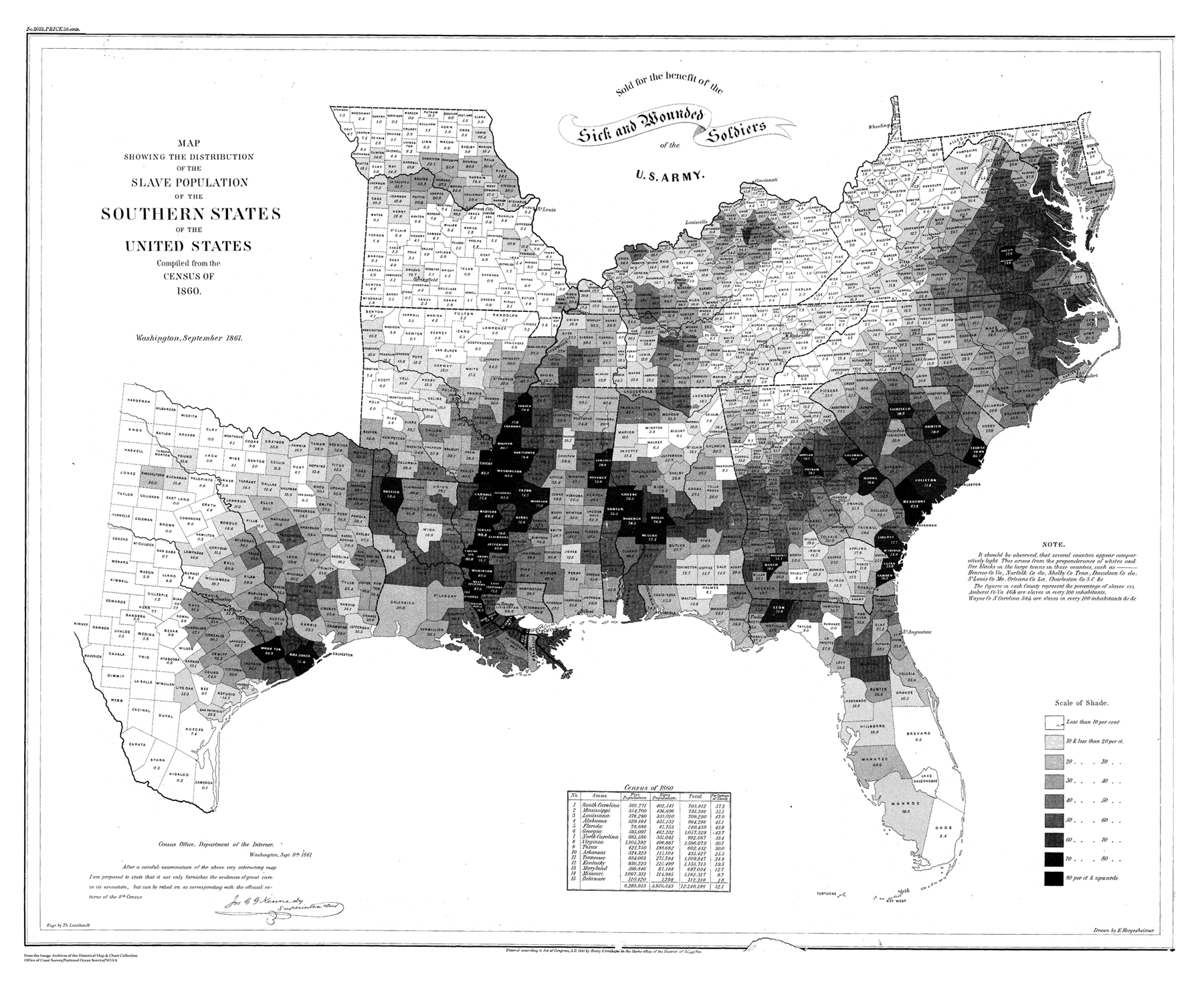

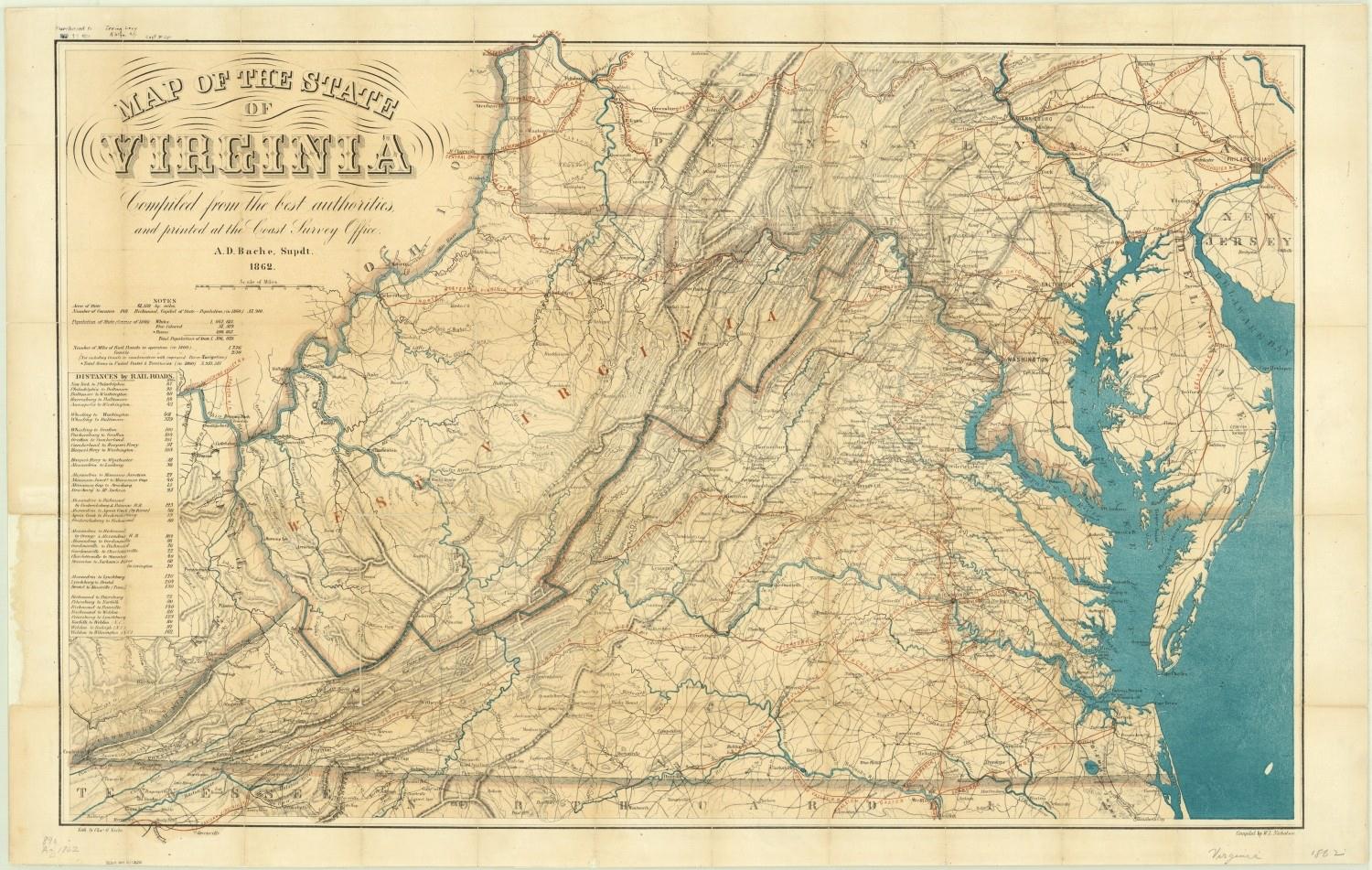

On the eve of conflict, the Coast Survey published two of the most important battle maps for the coming war. They were battle maps in the same sense that Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly was a call to arms. In June 1861, the Coast Survey prepared a unique map, lithographed by a commercial printer, which showed the proportions of the slave populations of each of the counties of the state of Virginia, based on the data from the recently released 1860 Census. In September of 1861, the Survey completed a revised version of the Virginia map, and also a larger map, showing the same slave proportions of county populations for all of the Southern slave-owning states. The maps were utterly different from anything the Coast Survey had ever produced. Thus in 1860, on the eve of war, the Survey had completed a review and improvement of the entire system of cartography as practiced since Bache’s arrival. One of the first major applications of the new systems was the display of the slavery populations in the Southern states, where Coast Survey adapted the new system of hachures to display topographic relief to the task of political and moral relief.

As noted in Albert Theberge’s history of the Coast Survey, a not insignificant aspect of the service of the Coast Survey in the Civil War was that an entire generation of Union Army and Navy officers and personnel had been trained in geodesy and surveying from service with the Coast Survey. Importantly, they had received their training in many of the most critical geographical areas where the later war was fought. The terrestrial battles of the war in the south had much to do with massing and transporting huge armies and their supplies, with sieges and attacks, with rapid movements and with railroads. In response, the Coast Survey developed unique series of territorial maps, derived from a variety of sources. They were unlike any maps the Survey had ever produced, in several respects. In order to accomplish this, the Survey created an entire new division in the headquarters, the “Lithographing Division. The utility and iconic status of these Coast Survey maps for the Union war effort is captured in Francis Carpenter’s painting of 1864, which hangs in the Senate wing of the U.S. Capitol, of Abraham Lincoln preparing to read the Emancipation Proclamation to his cabinet for the first time. The two maps visible in the painting are the slavery map and the map of the state of Virginia, both produced by the Coast Survey.

Eventually the war concluded. Virtually every aspect of Bache’s strategy for the Survey — the blockade, the new and innovative map series, and much else — had proved original and successful. Sadly, Bache was not able to experience the fruits of his labor. Alexander Dallas Bache’s health declined as the war progressed. While overseeing construction of fortifications to defend Philadelphia against possible attack in May 1864, Bache suffered some sort of debilitating stroke or other disorder. On February 17, 1867, Alexander Dallas Bache died, and, thus, the greatest leader of the U.S. Coast Survey, who guided the Survey in the war, was also essentially Coast Survey’s last casualty of the Civil War.

Editor’s note: Many thanks to Dr. Cloud for directing us to this fascinating material–and humble apologies for the fragmented nature of the extracts included here.