The following Climate Central article was written by Alison Kanski and posted July 28, 2015, with the title above:

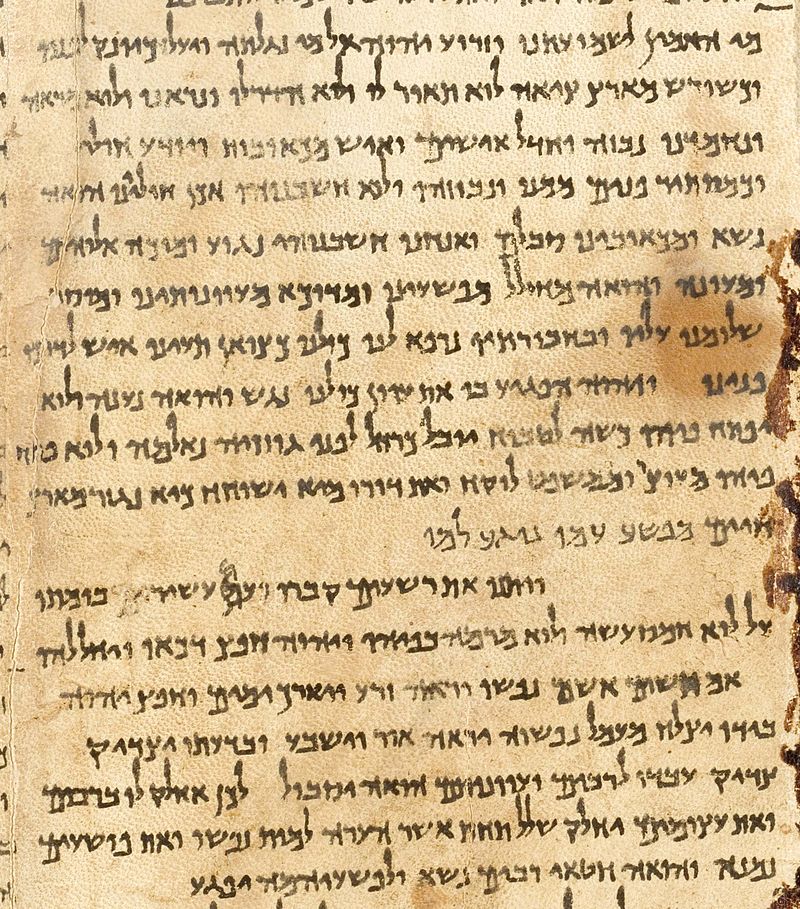

Radiocarbon dating has been helping put the planet’s history in the right order since it was first invented in the 1940s, giving scientists a key way to determine the age of artifacts like the Dead Sea Scrolls and the Shroud of Turin. Thanks to fossil fuel emissions, though, the method used to date these famous artifacts may be in for a change.

The burning of fossil fuels is altering the ratio of carbon in the atmosphere, which may cause objects tested in the coming decades to seem hundreds or thousands of years older than they actually are, according a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. A cotton T-shirt manufactured and tested in 2050 may appear to be the same age as an artifact from the 11th century when dated using the radiocarbon method. A new shirt made in 2100, if emissions continue unabated, could appear to come from the year 100, alongside something worn by a Roman soldier. In short, future human emissions may alter one of the most reliable methods for learning about the past.

Radiocarbon dating relies on the amount of radiocarbon, or carbon-14, remaining in an object to determine its approximate age. Radiocarbon is a radioactive form of carbon that’s created when nitrogen reacts with cosmic rays in the upper atmosphere. It occurs only in trace amounts, but it is present in every living thing.

Carbon-14 can combine with oxygen in the atmosphere to create carbon dioxide, which is then absorbed by plants and makes its way through the food chain. The amount of carbon-14 in living plants and animals matches the amount in the atmosphere, but when plants and animals die, they no longer absorb carbon-14. Because radiocarbon has a known rate of decay, scientists can determine about how long it has been since the plant or animal was alive. The lower the amount of radiocarbon, the older the object.

But big changes in the atmosphere can throw off this method, like releasing tons of extra carbon dioxide into the air from burning fossil fuels. Because fossil fuels like coal and oil are so old, they have no radiocarbon left. When burned, they increase the amount of carbon dioxide, which dilutes the radiocarbon in the atmosphere and the amount that can be absorbed by organic material. “Fossil fuels have lost all of their radiocarbon over millions of years of radioactive decay,” said Heather Graven, author of the study published last week. “This makes the atmosphere appear as though it has ‘aged.’”

Scientists are used to a bit of wiggle with carbon-14 dating; it can vary as much as 30 to 100 years from the actual age. But the changes from emissions will require some extra adjustment, even in the study’s best-case-scenario emissions projection. “If emissions are rapidly reduced, then the decrease in the fraction of radiocarbon in the atmosphere will be equivalent to only about a hundred years of radioactive decay,” said Graven.

For those who use carbon dating, like archaeologists, physicists, forensic scientists, and even art historians, the change in radiocarbon will complicate their work, according to Timothy Jull, a radiocarbon scientist. “There are all these complicated effects,” said Jull, also a professor of geosciences at University of Arizona, who was not involved in the study. “There will be some ambiguities about whether it’s 300 years old or relatively recent. We’re going to need more information.”

Scientists could begin seeing the effects on radiocarbon as soon as 2020, when the ratio is expected to drop below pre-industrial levels, according to Graven. But she hopes the projections in her study could also help scientists prepare for the changes to come. And, hopefully, they will keep scientists from mistaking a T-shirt from 2050 for William the Conqueror’s blouse.