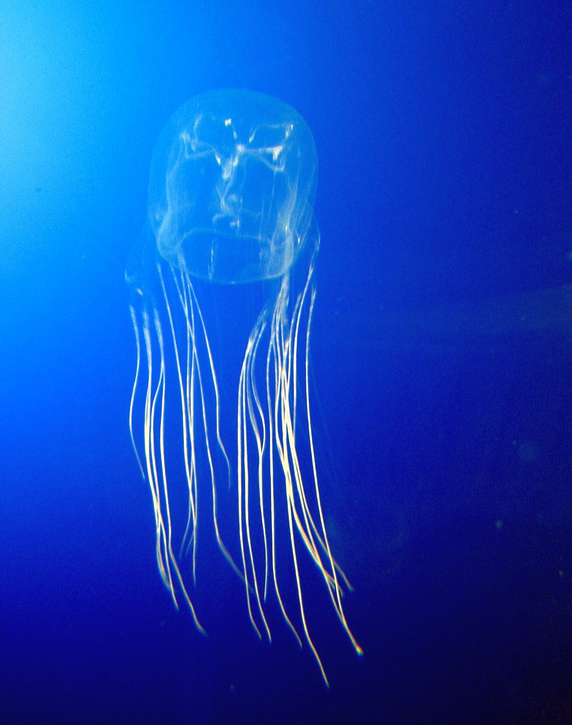

A huge cluster of jellyfish recently clogged the cooling water intakes of the Oskarshamn nuclear plant in southeastern Sweden, forcing it to shut down. This marks the second time that jellyfish have caused the closure of the Swedish plant. The same thing happened to California’s Diablo Canyon facility last year, and four nuclear reactors in Japan, Israel, and Scotland were forced to shut down in 2011, due to swarms of jellyfish which clogged the plants’ cooling systems.

Apart from impacting nuclear plants, blooms of jellyfish can have seriously negative impacts on coastal populations, tourism, and marine-related industries. A massive jellyfish invasion wiped out the Irish salmon industry in 2007, Tunisian fish farms lost a year’s production to jellyfish swarms in 2009, and jellyfish kill 20-40 people a year in the Philippines. Since 1982, the Sea of Japan has been invaded by huge masses of Nomura’s jellyfish, weighing up to 440 pounds and measuring 6.5 feet in diameter, which clog fishing nets and even overturn trawlers.

Enter the robot jellyfish exterminator: “A [South Korean] team led by KAIST Civil and Environmental Engineering Department’s Professor Hyeon Myeong has just finished testing the cooperative assembly robot for jellyfish population control, named JEROS, in the field. The rising number of accidents and financial losses by the fishing industry, estimated at 300 billion won [about $280,000,000] per year, caused by the recent swarm of jellyfish in coastal waters has been a major problem for many years. The research team led by Prof. Hyeon Myeong began developing an unmanned automated system capable of eradicating jellyfish in 2009 and has since completed field tests last year with success.

This year, JEROS’s performance and speed has been improved with the ability to work in formation as a cooperative group to efficiently exterminate jellyfish. An unmanned aquatic robot JEROS with a mountable grinding part is buoyed by two cylindrical bodies that utilize propulsion motors to move forward and reverse, as well as rotate 360 degrees. Furthermore, GIS (geographic information system)-based map data is used to specify the region for jellyfish extermination, which automatically calculates the path for the task. JEROS then navigates autonomously, using a GPS (Global Positioning System) receiver and an INS (inertial navigation system).

The assembly robots maintain a set formation pattern, while calculating its course to perform jellyfish extermination. The advantage of this method is that there is no need for individual control of the robots. Only the leader robot requires the calculated path, and the other robots can simply follow in a formation by exchanging their location information via wireless communication (ZigBee method).

JEROS uses its propulsion speed to capture jellyfish into the grinding part on the bottom, which then suctions the jellyfish toward the propeller to be exterminated. The field test results show that three assembly robots operating at 4 knots (7.2km/hour) dispose of jellyfish at the rate of about 900kg/hour.

The research team has currently completed testing JEROS at Gyeongnam Masan Bay and is expected to further experiment and improve the performance at various environment and conditions. JEROS may also be utilized for other purposes, including marine patrols, prevention of oil spills, and waste removal in the sea”.

An article in BioScience questions recent claims that jellyfish are increasing worldwide: “During the past several decades, high numbers of gelatinous zooplankton species have been reported in many estuarine and coastal ecosystems. Coupled with media-driven public perception, a paradigm has evolved in which the global ocean ecosystems are thought to be heading toward being dominated by “nuisance” jellyfish. We question this current paradigm by presenting a broad overview of gelatinous zooplankton in a historical context to develop the hypothesis that population changes reflect the human-mediated alteration of global ocean ecosystems. To this end, we synthesize information related to the evolutionary context of contemporary gelatinous zooplankton blooms, the human frame of reference for changes in gelatinous zooplankton populations, and whether sufficient data are available to have established the paradigm. We conclude that the current paradigm in which it is believed that there has been a global increase in gelatinous zooplankton is unsubstantiated, and we develop a strategy for addressing the critical questions about long-term, human-related changes in the sea as they relate to gelatinous zooplankton blooms.”

Editor’s note: See the May 26, 2013 article, “Jellyfish: If we can’t beat ’em, why not eat ’em?”

Article by Bill Norrington