“The steelhead trout is a remarkable trout species that lives in both freshwater and ocean environments. Steelhead trout are born in freshwater streams/rivers. They typically spend their first year in freshwater habitats and then migrate to the ocean where they spend most of their adult life. Adult steelhead trout are anadromous, meaning they migrate up freshwater streams and rivers to spawn. Steelhead trout are native to streams and rivers along the Pacific Coast from Mexico to Alaska. Populations of southern steelhead historically existed in all of the larger watersheds within Santa Barbara County.

The Santa Ynez River is reported to have had the largest population of steelhead in all of Southern California, with estimates of 13,000 to 25,000 adults returning in the 1943-1944 run. Although the range of steelhead trout is still very large, from Alaska to northern Baja, populations in the southern portion of their range have been severely reduced. Since the beginning of the century, it is estimated that steelhead populations in Southern California have been reduced to less than one percent of their former population size. Due to this significant reduction, the Southern California steelhead trout population (which includes Santa Barbara County) has been federally designated as an endangered species by the National Marine Fisheries Service” (source).

Mark Capelli is the South-Central/Southern California Coast Recovery Coordinator for NOAA’s Protected Resources Division of the National Marine Fisheries Service devoted to recovery of salmon and steelhead. The Protected Resources Division is responsible for conservation and management programs involving endemic and migratory marine mammals and endangered species populations adjacent to California and in the southern and eastern tropical Pacific Ocean. The Division develops regulations and management measures to protect, conserve, and restore marine mammal and endangered species populations (source).

As the Steelhead Recovery Coordinator for Southern/South-Central California, Mark is particularly involved with a recovery plan for steelhead runs along the coast. The plan identifies the threats which have brought steelhead to the brink of extinction, sets out a general strategy for recovering the species to allow their removal from the list of threatened species, and describes a research and monitoring program to refine recovery goals and track the progress towards recovery. Priority recovery actions include: Establishing access above impassible barriers (road crossings, dams, debris basins), restoring flow regimes for migration and over-summering habitat, reducing point and non-point pollution sources, developing and implementing a comprehensive habitat monitoring and stock assessment program, and restoring ecological estuarine functions to support steelhead rearing and acclimation.

The following notes, “Atascadero Creek Steelhead Observation, Santa Barbara, CA,” were recently provided by Mark and are a poignant reminder that steelhead are literally in our backyards, fighting for survival:

Following a moderate sized rain on March 7-9th, flows in the tributaries to the Goleta Slough (principally, Maria Ignacio, Atascadero, and San Jose) breached the sandberm at the mouth of the Goleta Slough, creating opportunities for winter steelhead (Oncorhynchus mykiss) to enter the estuary and move into upstream spawning and rearing habitat. Several weeks later, on March 18-19th, a pair of adult steelhead were observed in lower Atascadero Creek, below the Patterson Avenue Bridge. A steelhead spawning nest (redd) created by the pair was visible approximately 10 meters downstream of the Patterson Avenue Bridge (Figure 1 and 2).

The two adult steelhead were observed lying in about 0.75 meter of water near the eastern side of the redd. The larger of the two fish (c. 63 cm) showed some minor fungal growth on the dorsal side (in the vicinity of the dorsal fin). The smaller of the two fish (c. 58 cm) did not appear to show as much fungal growth. Neither fish exhibited any significant fin erosion, though both fish had developed a red band along their lateral line and gill covers (operculum), an indication that the fish had been in freshwater for at least several weeks. Neither fish was active over the redd when they were observed, but they would periodically swim across the redd as they milled in the associated pool (Figure 2).

Atascadero Creek in this reach is a low-gradient stream with generally slow moving water and few falls or riffles. It has a natural bottom and is vegetated on both banks with a variety of native vegetation, including mule fat, willow, and sycamore. However, there is a concrete drop structure under the Patterson Avenue Bridge, which is approximately 1.5 meters above the current water surface area immediately below the drop structure; additionally, there is a concrete apron that extends upstream approximately the width of the Patterson Avenue Bridge. Under the current water conditions, this drop structure inhibits (and effectively prohibits) the upstream movement of these fish and, most likely, also inhibits the downstream movement of fish from upstream reaches of Atascadero Creek, including both adults and juveniles (Figure 3).

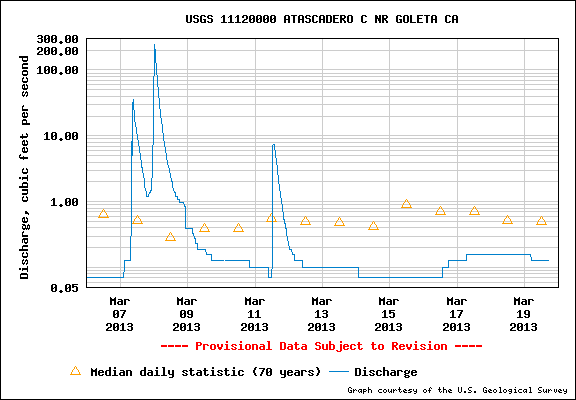

The Atascadero Creek flow in to the pool below the Patterson Avenue Bridge was approximately 0.5 cfs at the time the observation of the adult steelhead (and juvenile O. mykiss) were made. The water temperature was 14 c., and there was a slight discoloration of the water; additionally, the staff of the Regional Water Quality Control Board reports periodic super-saturated conditions in this reach of lower Atascadero Creek. Preliminary data from the U.S.G.S. gaging station on the Patterson Avenue Bridge (USGS 1112000) reported flows above 200 cfs on March 8, 2013 (Figure 4).

While recent rain/runoff events may have created conditions which facilitated the upstream migration of these (and possibly other) steelhead from the ocean and through the lower portions of the Goleta Slough, at the time of the observation, the sandberm at the mouth of the Goleta Slough was closed, though the water levels in the slough were near the top of the sandberm. There was evidence of a recent attempt to manually breach the sandberm at the far eastern end of the berm at the mouth of the Goleta Slough, though there was no evidence that this effort was successful (Figure 5).

Both adult steelhead appear to be in generally good condition, spawned out, and, possibly, ready to emigrate back downstream and out to sea if flow conditions permit and the sandberm at the mouth of the Goleta Slough is open to the ocean. A second, smaller storm event on April 6-7th may have provided an opportunity for these spawned out adult fish to return to the ocean, while additional steelhead were observed attempting to pass over the drop structure under the Patterson Avenue Bridge.

Editor’s note: A PDF of “A History of Steelhead and Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) in the Santa Ynez River Watershed, Santa Barbara County, California,” coauthored by Mark Capelli, can be found here. The Mark H. Capelli Southern California Steelhead Watershed Archive is available in Special Collections at the UCSB Library.

Fish Survey 8-13-10b.jpg)