The following article is by Steven Pinker, a Harvard University Professor of Psychology. This essay is adapted from his 2011 book, “The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined,” published by Viking.

On the day this article appears, you will read about a shocking act of violence. Somewhere in the world there will be a terrorist bombing, a senseless murder, a bloody insurrection. It’s impossible to learn about these catastrophes without thinking, “What is the world coming to?” But a better question may be, “How bad was the world in the past?” Believe it or not, the world of the past was much worse. Violence has been in decline for thousands of years, and today we may be living in the most peaceable era in the existence of our species.

The decline, to be sure, has not been smooth. It has not brought violence down to zero, and it is not guaranteed to continue. But it is a persistent historical development, visible on scales from millennia to years, from the waging of wars to the spanking of children. This claim, I know, invites skepticism, incredulity, and sometimes anger. We tend to estimate the probability of an event from the ease with which we can recall examples, and scenes of carnage are more likely to be beamed into our homes and burned into our memories than footage of people dying of old age. There will always be enough violent deaths to fill the evening news, so people’s impressions of violence will be disconnected from its actual likelihood. Evidence of our bloody history is not hard to find. Consider the genocides in the Old Testament and the crucifixions in the New, the gory mutilations in Shakespeare’s tragedies and Grimm’s fairy tales, the British monarchs who beheaded their relatives and the American founders who dueled with their rivals. Today the decline in these brutal practices can be quantified. A look at the numbers shows that over the course of our history, humankind has been blessed with six major declines of violence.

The first was a process of pacification: the transition from the anarchy of the hunting, gathering, and horticultural societies in which our species spent most of its evolutionary history to the first agricultural civilizations, with cities and governments, starting about 5,000 years ago. For centuries, social theorists like Hobbes and Rousseau speculated from their armchairs about what life was like in a “state of nature.” Nowadays we can do better. Forensic archeology—a kind of “CSI: Paleolithic”—can estimate rates of violence from the proportion of skeletons in ancient sites with bashed-in skulls, decapitations, or arrowheads embedded in bones. And ethnographers can tally the causes of death in tribal peoples that have recently lived outside of state control. These investigations show that, on average, about 15% of people in prestate eras died violently, compared to about 3% of the citizens of the earliest states. Tribal violence commonly subsides when a state or empire imposes control over a territory, leading to the various “paxes” (Romana, Islamica, Brittanica, and so on) that are familiar to readers of history. It’s not that the first kings had a benevolent interest in the welfare of their citizens. Just as a farmer tries to prevent his livestock from killing one another, so a ruler will try to keep his subjects from cycles of raiding and feuding. From his point of view, such squabbling is a dead loss—forgone opportunities to extract taxes, tributes, soldiers, and slaves.

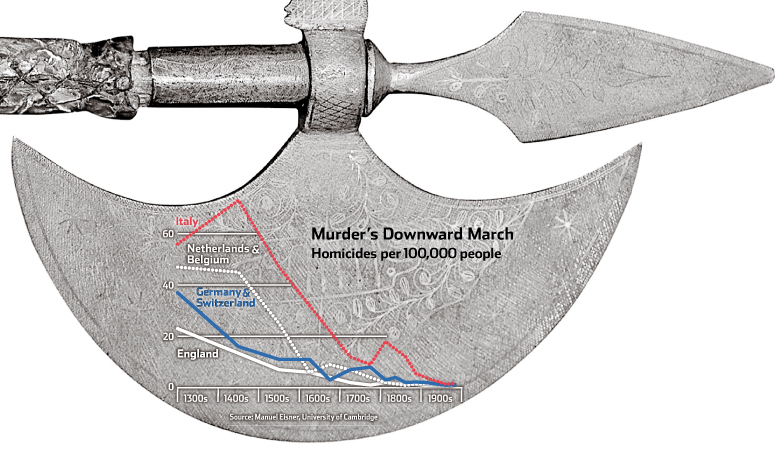

The second decline of violence was a civilizing process that is best documented in Europe. Historical records show that between the late Middle Ages and the 20th century, European countries saw a 10- to 50-fold decline in their rates of homicide. The numbers are consistent with narrative histories of the brutality of life in the Middle Ages, when highwaymen made travel a risk to life and limb and dinners were commonly enlivened by dagger attacks. So many people had their noses cut off that medieval medical textbooks speculated about techniques for growing them back. Historians attribute this decline to the consolidation of a patchwork of feudal territories into large kingdoms with centralized authority and an infrastructure of commerce. Criminal justice was nationalized, and zero-sum plunder gave way to positive-sum trade. People increasingly controlled their impulses and sought to cooperate with their neighbors.

The third transition, sometimes called the Humanitarian Revolution, took off with the Enlightenment. Governments and churches had long maintained order by punishing nonconformists with mutilation, torture, and gruesome forms of execution, such as burning, breaking, disembowelment, impalement, and sawing in half. The 18th century saw the widespread abolition of judicial torture, including the famous prohibition of “cruel and unusual punishment” in the eighth amendment of the U.S. Constitution. At the same time, many nations began to whittle down their list of capital crimes from the hundreds (including poaching, sodomy, witchcraft, and counterfeiting) to just murder and treason. And a growing wave of countries abolished blood sports, dueling, witchhunts, religious persecution, absolute despotism, and slavery.

The fourth major transition is the respite from major interstate war that we have seen since the end of World War II. Historians sometimes refer to it as the Long Peace. Today we take it for granted that Italy and Austria will not come to blows, nor will Britain and Russia. But centuries ago, the great powers were almost always at war, and until quite recently, Western European countries tended to initiate two or three new wars every year. The cliché that the 20th century was “the most violent in history” ignores the second half of the century (and may not even be true of the first half, if one calculates violent deaths as a proportion of the world’s population). Though it’s tempting to attribute the Long Peace to nuclear deterrence, non-nuclear developed states have stopped fighting each other as well. Political scientists point instead to the growth of democracy, trade and international organizations—all of which, the statistical evidence shows, reduce the likelihood of conflict. They also credit the rising valuation of human life over national grandeur—a hard-won lesson of two world wars.

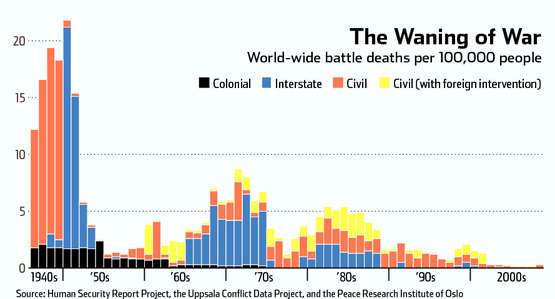

The fifth trend, which I call the New Peace, involves war in the world as a whole, including developing nations. Since 1946, several organizations have tracked the number of armed conflicts and their human toll world-wide. The bad news is that for several decades, the decline of interstate wars was accompanied by a bulge of civil wars, as newly independent countries were led by inept governments, challenged by insurgencies and armed by the cold war superpowers. The less bad news is that civil wars tend to kill far fewer people than wars between states. And the best news is that, since the peak of the cold war in the 1970s and ’80s, organized conflicts of all kinds—civil wars, genocides, repression by autocratic governments, terrorist attacks—have declined throughout the world, and their death tolls have declined even more precipitously. The rate of documented direct deaths from political violence (war, terrorism, genocide, and warlord militias) in the past decade is an unprecedented few hundredths of a percentage point. Even if we multiplied that rate to account for unrecorded deaths and the victims of war-caused disease and famine, it would not exceed 1%. The most immediate cause of this New Peace was the demise of communism, which ended the proxy wars in the developing world stoked by the superpowers and also discredited genocidal ideologies that had justified the sacrifice of vast numbers of eggs to make a utopian omelet. Another contributor was the expansion of international peacekeeping forces, which really do keep the peace—not always, but far more often than when adversaries are left to fight to the bitter end.

Finally, the postwar era has seen a cascade of “rights revolutions”—a growing revulsion against aggression on smaller scales. In the developed world, the civil rights movement obliterated lynchings and lethal pogroms, and the women’s-rights movement has helped to shrink the incidence of rape and the beating and killing of wives and girlfriends. In recent decades, the movement for children’s rights has significantly reduced rates of spanking, bullying, paddling in schools, and physical and sexual abuse. And the campaign for gay rights has forced governments in the developed world to repeal laws criminalizing homosexuality and has had some success in reducing hate crimes against gay people.

Why has violence declined so dramatically for so long? Is it because violence has literally been bred out of us, leaving us more peaceful by nature? This seems unlikely. Evolution has a speed limit measured in generations, and many of these declines have unfolded over decades or even years. Toddlers continue to kick, bite and hit; little boys continue to play-fight; people of all ages continue to snipe and bicker; and most of them continue to harbor violent fantasies and to enjoy violent entertainment. It’s more likely that human nature has always comprised inclinations toward violence and inclinations that counteract them—such as self-control, empathy, fairness, and reason—what Abraham Lincoln called “the better angels of our nature.” Violence has declined because historical circumstances have increasingly favored our better angels.

The most obvious of these pacifying forces has been the state, with its monopoly on the legitimate use of force. A disinterested judiciary and police can defuse the temptation of exploitative attack, inhibit the impulse for revenge and circumvent the self-serving biases that make all parties to a dispute believe that they are on the side of the angels. We see evidence of the pacifying effects of government in the way that rates of killing declined following the expansion and consolidation of states in tribal societies and in medieval Europe. And we can watch the movie in reverse when violence erupts in zones of anarchy, such as the Wild West, failed states, and neighborhoods controlled by mafias and street gangs, who can’t call 911 or file a lawsuit to resolve their disputes but have to administer their own rough justice.

Another pacifying force has been commerce, a game in which everybody can win. As technological progress allows the exchange of goods and ideas over longer distances and among larger groups of trading partners, other people become more valuable alive than dead. They switch from being targets of demonization and dehumanization to potential partners in reciprocal altruism. For example, though the relationship today between America and China is far from warm, we are unlikely to declare war on them or vice versa. Morality aside, they make too much of our stuff, and we owe them too much money. A third peacemaker has been cosmopolitanism—the expansion of people’s parochial little worlds through literacy, mobility, education, science, history, journalism, and mass media. These forms of virtual reality can prompt people to take the perspective of people unlike themselves and to expand their circle of sympathy to embrace them.

These technologies have also powered an expansion of rationality and objectivity in human affairs. People are now less likely to privilege their own interests over those of others. They reflect more on the way they live and consider how they could be better off. Violence is often reframed as a problem to be solved rather than as a contest to be won. We devote ever more of our brainpower to guiding our better angels. It is probably no coincidence that the Humanitarian Revolution came on the heels of the Age of Reason and the Enlightenment, that the Long Peace and rights revolutions coincided with the electronic global village. Whatever its causes, the implications of the historical decline of violence are profound. So much depends on whether we see our era as a nightmare of crime, terrorism, genocide and war or as a period that, in the light of the historical and statistical facts, is blessed by unprecedented levels of peaceful coexistence.

Bearers of good news are often advised to keep their mouths shut, lest they lull people into complacency. But this prescription may be backward. The discovery that fewer people are victims of violence can thwart cynicism among compassion-fatigued news readers who might otherwise think that the dangerous parts of the world are irredeemable hell holes. And a better understanding of what drove the numbers down can steer us toward doing things that make people better off rather than congratulating ourselves on how moral we are. As one becomes aware of the historical decline of violence, the world begins to look different. The past seems less innocent, the present less sinister. One starts to appreciate the small gifts of coexistence that would have seemed utopian to our ancestors: the interracial family playing in the park, the comedian who lands a zinger on the commander in chief, the countries that quietly back away from a crisis instead of escalating to war. For all the tribulations in our lives, for all the troubles that remain in the world, the decline of violence is an accomplishment that we can savor—and an impetus to cherish the forces of civilization and enlightenment that made it possible.