Under the heading “Urbanization, Climate Change, and Indigenous Populations: Finding USAID’s Comparative Advantage,” Kayly Ober wrote the following May 26 posting of the Wilson Center’s online news:

“Part of the outflow of migrants from rural areas of many Latin American countries has settled in remote rural areas, pushing the agricultural frontier further into the forest,” writes David López-Carr in a recent article in Population & Environment, “The population, agriculture, and environment nexus in Latin America.” In a May 4 presentation at the Latin American and Carribbean (LAC) Economic Growth and Environment Strategic Planning Workshop in Panama City, Panama, sponsored by USAID and the Woodrow Wilson Center, he discussed how to integrate family planning and environmental services in rural Latin America.

Latin America is one of the most highly urbanized continents in the world, with an average of 75 percent of the population living in cities. However, “there are two Latin Americas,” said López-Carr at the workshop, which was sponsored by the Woodrow Wilson Center’s Environmental Change and Security Program and Brazil Institute, as well as the U.S. Agency for International Development. Largely developed countries like Chile, Argentina, and Uruguay are close to 90 percent urbanized, while Guatemala, Ecuador, and Bolivia are about 50 percent. In less urbanized countries, rural-rural migrants in search of agricultural land remain a major driving force behind forest conversion, he said.

Between 1961 and 2001, Central America’s rural population increased by 59 percent, said Lopez-Carr. The increasing density of the rural population had a negative impact on forest reserves: a 15 percent increase in deforestation totaling some 13 million hectares.

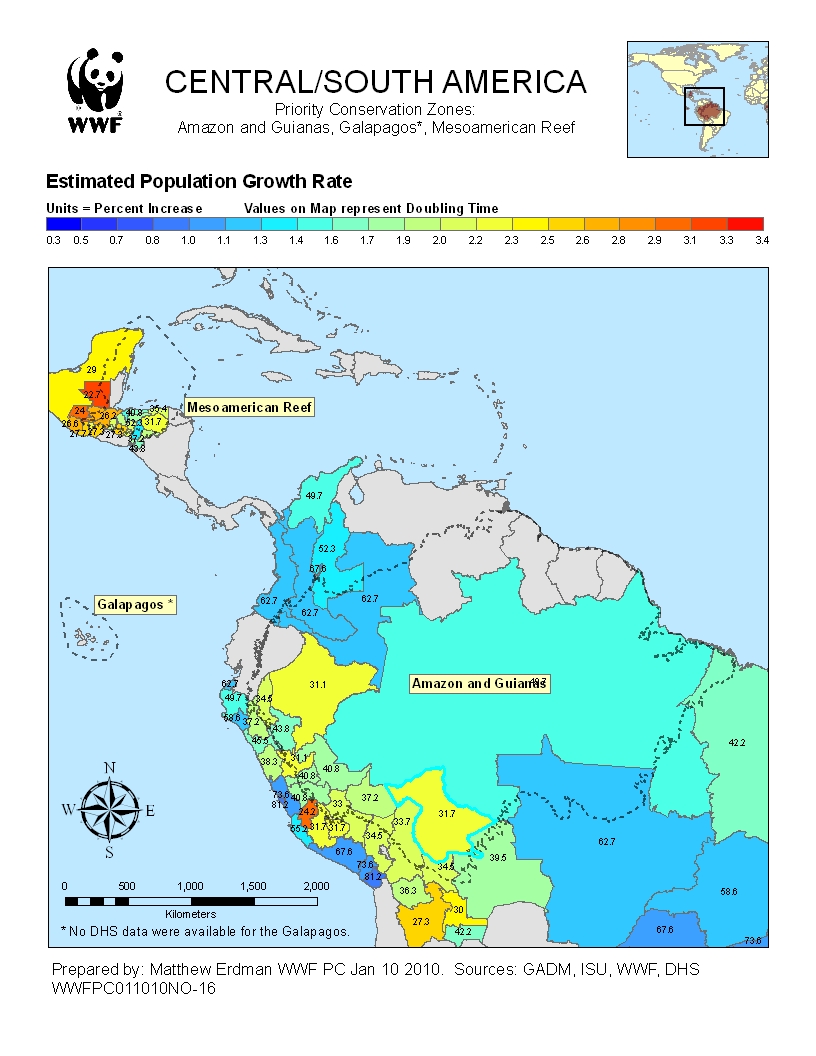

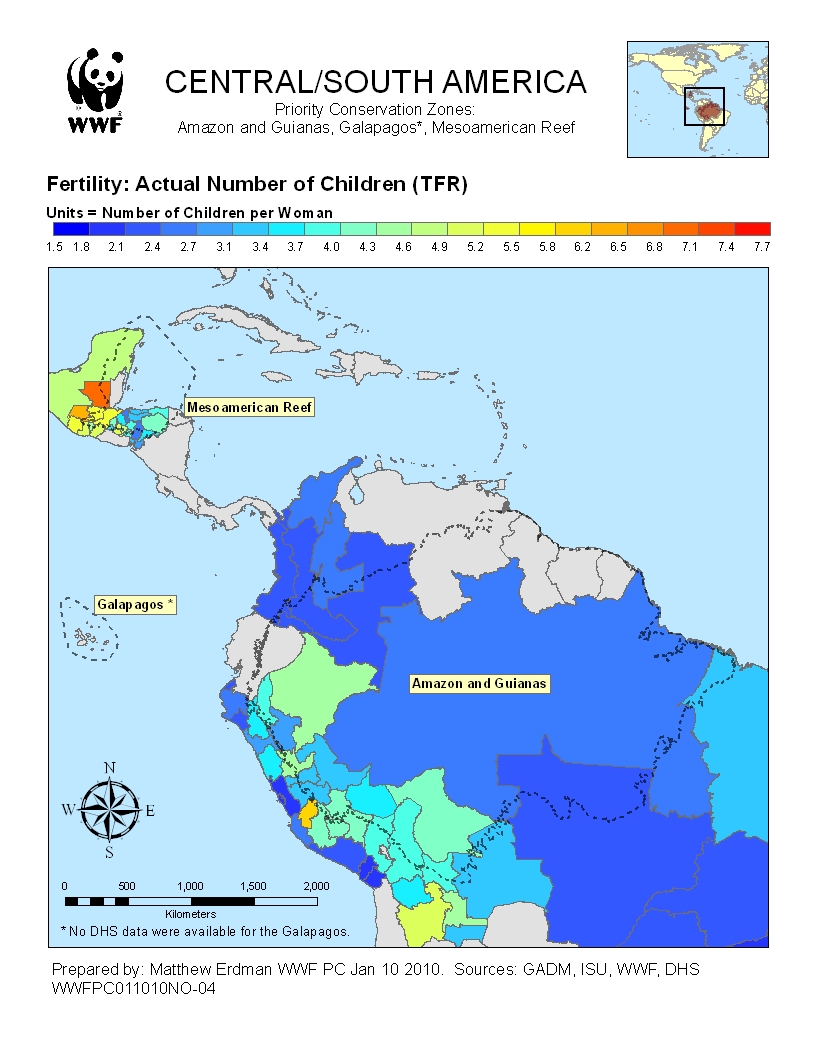

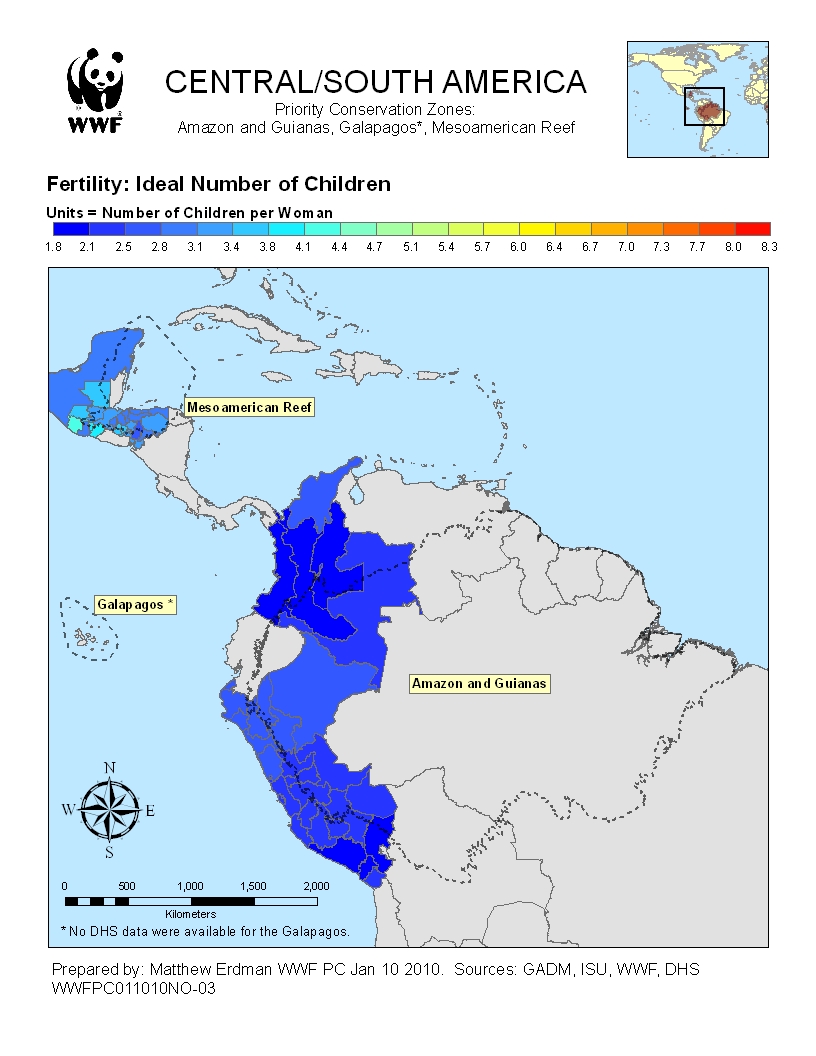

“Rural areas of Latin America still have high fertility rates but (unlike much of rural Africa, for example) also have a high unmet demand for contraception, meaning that improved contraceptive availability would likely result in a rapid and cost-effective means to reduce population pressures in priority conservation areas,” he said. Additionally, remote rural areas with high population growth rates tend to be associated with indigenous populations located in close proximity to protected forests.

For example, in Guatemala, communities surrounding Sierra de Lacandon National Park have, since 1990, grown by 10 percent each year, with birthrates averaging eight children per woman. Larger communities and larger households have led to agricultural expansion, which infringes on the park and accelerates deforestation in one of the most biologically diverse biospheres in the world, said López-Carr.

Based on these demographic and environmental trends, López-Carr suggested USAID’s work in the region should focus on rural maternal and child health, and education – especially for girls. Not only does USAID already invest in such programs, but they only cost pennies per capita and could reduce the number of rural poor living in Latin American cities by tens of millions.

Given the strong links between population density and deforestation in Latin America, expanding access to family planning would also be a smart investment in forest conservation and climate mitigation, López-Carr concluded.

References:

Carr, D. L. (2009). Migration and Tropical Deforestation: Why Population Matters. Progress in Human Geography. 33(9): 355-378.

Carr, D. L., A.C. Lopez, R.E. Bilsborrow (2009). The Population, agriculture, and environment nexus in Latin America: Country-level evidence from the latter half of the 20th century. Population and Environment. 30:222–246.

López-Carr , D. (2010). Mapping Population and Health onto Priority Conservation Zones. WWF PHE Series. 43 pp.

López-Carr , D., M Erdman, A. Zvoleff (2010 forthcoming). How are population patterns different in ecological priority areas? Mapping demography onto conservation areas. Proceedings of the European Population Conference. September 1-4, 2010, Vienna, Austria.